Buck Zaidel has a keen eye for Civil War photographs at the intersection of art and history.

“Whether it’s the photographer’s skill or magic, the remnant of light meeting lens and that lingering shadow is something I strive to find,” Zaidel observes.

The ability to spot such images did not happen overnight. Zaidel honed his skill over years poring through photographs from the sun-soaked fields of the world famous Brimfield Antique Flea Market to a myriad of Civil War collector shows, auctions and just about everywhere else. Zaidel leaves no stone unturned in his quest to acquire images that meet his criteria.

The journey began in childhood: A family trip to Gettysburg; Britains toy soldiers; Civil War picture books around the time of America’s bicentennial. Later, when he attended dental school at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., Zaidel often biked to the Lincoln Memorial to take in the towering figure and read and reread the words spoken by the martyred president who saved the nation. His interest in Abraham Lincoln grew and connected more broadly to the Civil War, and eventually led to collecting artifacts.

I’m also very appreciative of the relationships established over these many years with fellow members of the Civil War collecting community who freely shared their knowledge and expertise, some good stories, a few laughs—and if an item came to market that they thought would be valued in my collection provided me with an opportunity to acquire it. I’m most grateful for that.

Zaidel’s Civil War interest flipped upside down about 1988. By this time, he had moved to Connecticut. One day, he stopped by the Middlesex County Historical Society in Middletown, Conn., to make a research inquiry. He met Director Dione Longley, who introduced him to a unique collection of artifacts, mostly identified items brought home by Union veterans. Coming face to face with these personal relics forever changed him. As he tells it, “I was and still am a Lincoln fan, but rather than Grant, Lee, Sherman and Sheridan, the common Union soldier became my main pursuit.”

Zaidel purchased his first soldier photograph about 1990. Two years later, a chance letter marked the beginning of a memorable phase of his collecting life. It contained a copy of a soldier carte de visite offered for sale by a man unknown to him—Bernie Rogers. Zaidel recalls the backstory. “A dealer and collector acquaintance that I’d met at local shows, Fred Zwick, had kindly passed my name along to his friend and mentor Bernie Rogers. I bought the carte de visite from Bernie, and was invited to his house. There I saw the most amazing collection. Bernie was an old time collector’s collector and occasional dealer who had worked part time at Bannerman’s Island in the 1960’s. I believe he took his pay in the antique military surplus goods that filled up the castle in the Hudson River not far from West Point. Soon thereafter, we were venturing on 10 hour road trips—with no radio—just Bernie’s stories of the early days of collecting, his wish list for the upcoming show, plans for his next exhibit, along with an occasional joke, to shows in Mansfield, Ohio, Richmond, Chantilly, and Fredericksburg, Va. This opened a whole new world of opportunity as I had a chance to meet some of the leading voices in the collecting fraternity along with countless great times.” Rogers passed away in 2011.

Zaidel carries on in the Rogers tradition. He also points to another man who shaped his collecting philosophy, Thomas Harris. A collector and dealer based in New York City, Harris inspired him to seek out those images at the confluence of artistry and historical significance.

The inspiration of Rogers and Harris, and the generosity of so many others, is reflected in Heroes For All Time: Connecticut Civil War Soldier’s Tell Their Stories, a book Zaidel co-authored with Dione Longley in 2015. “Di is a historian, researcher extraordinaire, a sublime writer, and most importantly, is always eager to hear about some newly acquired Civil War treasure of mine,” Zaidel notes. “This is shortly followed by a response from her research department with more information than I could ever have hoped to find.”

Zaidel would not be where he is today without his family. His parents always encouraged and supported his hobby, as has his wife, Cathy, and children, Peter and Kaitlin. They “patiently listened to stories about little sepia-toned images, and how each new one was better than the last,” Zaidel recalls with pleasure. “I’m also very appreciative of the relationships established over these many years with fellow members of the Civil War collecting community who freely shared their knowledge and expertise, some good stories, a few laughs—and if an item came to market that they thought would be valued in my collection provided me with an opportunity to acquire it. I’m most grateful for that.”

Two pards for each other and the flag.

Though this lone cannon sits undisturbed as if a silent witness to Civil War, chances are it belched forth death from its muzzle on more than one battlefield.

Two enlisted men have laid out quite a feast in front of their camp scene backdrop. A slab of meat has been prepared, utensils are handy, fresh red-ripe apples are in season, and the tin cup sits idle as red wine is paired with beef that night, in fine glassware no less. Though the soldiers are not identified, their hat brass reveals they served in Company F of the 2nd artillery.

“Letters from home are like sunshine after a storm,” observed a Connecticut soldier during the war. The sentiment is echoed in this portrait of two privates reading a letter, while resting on their army blanket in a staged photo that might capture the highlight of a soldier’s week.

An anonymous photographer took these members of the 4th New York Heavy Artillery from picket duty to posterity. So says the period inscription on the back of the mount of this carte of Pvt. James Beckwith and Sgt. George S. Farwell of Battery C: “Just off picket duty. 48 hour tour.” Both men survived the war.

When the big guns, rifle-musket fire and a cavalry charge aren’t enough to turn the tide of battle, it’s time to pull out the camp axes, the cutlery and fists. Three gray clad privates, possibly from an early war Ohio unit, show their eagerness in helping to put down the rebellion.

On occasion, the back of a carte is as significant as the portrait on the front. Case in point: This image of Woods Maguire of the 3rd U.S. Infantry includes in a fine, educated hand, his particulars clearly presented in ink on the print. But the dramatic story is told more completely on the verso: “Maguire was 1st Lt when killed. A shell cut off his head in the afternoon of 1st July, 1862 at the Battle of Malvern Hills. We buried him that night at 12 o’clock under a cherry tree.” The note is signed by his captain, Joseph Addison McCool. A Pennsylvania newspaperman prior to the war, McCool was dismissed from the army in 1864 and died three years later.

Free at last. From the left, Capt. Julius Sanford, Capt. Dwight Hopkins, and Maj. Robert C. Anthony in tattered uniforms and broad-brimmed straw hats after their release from Camp Ford, a prisoner of war facility in Tyler, Texas. Sanford and Hopkins, part of a group of 13 officers from the 23rd Connecticut Infantry, fell into enemy hands while guarding a rail line at Bayou Boeuf, La., in June 23, 1863. They suffered confinement for 14 months. Confederates captured Maj. Anthony, who served in the 2nd Rhode Island Cavalry, the same day in Brashear City, La.

Dad’s large, comforting hand enhances the intimacy between father and son. Images of this genre captured the moment and the historic nature of the times, and specifically dad’s role in it. It likely represented a lasting memento, should the war prevent dad’s return from the service.

A soldier prepares for a meal with his fork ready and loaded. Opposite his image, in a mismatched case, a map of the upper Midwest is not his only connection to home. Three locks of hair carefully tied are reminders of a family apart. Two appear to be distinctly delicate and make one think of youngsters separated from their Dad.

An infantryman in heavy marching order stands at “Parade Rest.” His name and fate are currently lost in time.

J. Henri Burwell of the 15th Connecticut Infantry posed for his likeness with all the trappings of a mid-19th century warrior. Nattily attired, he is armed with a rifled–musket and bayonet, a non-commissioned officer’s sword and two gleaming brass eagle breast plates. But all his military finery proved no defense from the enemy that attacked the regiment at New Bern, N.C., in the late summer of 1864—Yellow Fever. Nearly 70 soldiers died of disease, including Burwell, before cooler weather set in.

Home sweet home. Capt. Samuel Adolphus Judd of the 3rd Michigan Infantry poses with his wife, Clarissa, and children, Willie and Jennie, in front of the log house built by Judd’s comrades in Company A. Beloved by his men, the good captain died soon after at the May 31, 1862, Battle of Fair Oaks. Clarissa became a widow, and never remarried.

At first glance, this soldier appears to be a Confederate armed with a Henry Rifle. His loyalties however, lay with the Union, for he is William H. “Will” Shirley, a private in Company H of the 2nd West Virginia Infantry. Shirley served on detached duty as a scout in September and October 1863, and is likely pictured here in a uniform that would allow him to blend in with those of Southern persuasion. A few months after his stint as a scout ended, the regiment reorganized as the 5th West Virginia Cavalry. Shirley ended the war as a corporal and lived until 1907.

A Veteran Reserve Corps private with cocked cap strums a tune for his well-dressed lady companion.

A view of camp life enacted countless times, but from a photographer’s perspective rarely encountered. From within the soldier’s tent, a canteen, a tent-pole, and even buttonholes and grommets frame the scene of a soldier getting a shave while a tasseled cap rests upon his knee.

Expressions of patriotism took many forms during the war, as evidenced by this soaring sentinel sculpted from stone. One can easily imagine this eagle perched above a soldier’s monument or village court house, its outspread wings beckoning citizens to pause and honor the brave.

A New York Zouave drummer, finely over painted, leaps from this carte in vivid color unfazed by the intervening 150 years.

How close did this innocent appearing youth get to the terror of war? Did he peddle these bottled beverages to thirsty soldiers?

Capt. Enos Washington Thayer of the 26th Massachusetts Infantry suffered a wound on Sept. 19, 1864, at the Third Battle of Winchester, Va. The injury proved mortal, and he succumbed to it less than a month later. When Thayer’s effects reached home, his wife, Elizabeth—dressed in mourning attire—memorialized his sacrifice and loss by posing for a carte de visite with hand resting upon a vacant chair. Her late husband’s hat, sash, sword and belt sit on the table behind her.

Sgt. Joseph Norris Collins (1827-1918) is impeccably dressed in the uniform and bearskin plumed hat of his New Haven, Conn., militia unit, the 2nd Company Horse Guards. Next to him sits his flag-bearing son Frederick (born 1856), dressed in a Zouave-inspired soldier suit.

The hat brass and Second Corps badge of this unidentified private, above, just begin to tell the story of the hard-fighting 14th Connecticut Infantry. The regiment found itself at the Sunken Road at Antietam, charging Marye’s Heights at Fredericksburg, and behind the stonewall near The Angle at Gettysburg. In the last-named battle, Pvt. Elijah William Bacon of Company F received the Medal of Honor for leaping over the stonewall, and sprinting out to capture the flag of the 16th North Carolina during the culmination of Pickett’s Charge. He died less than a year later in The Wilderness. Might this have been him?

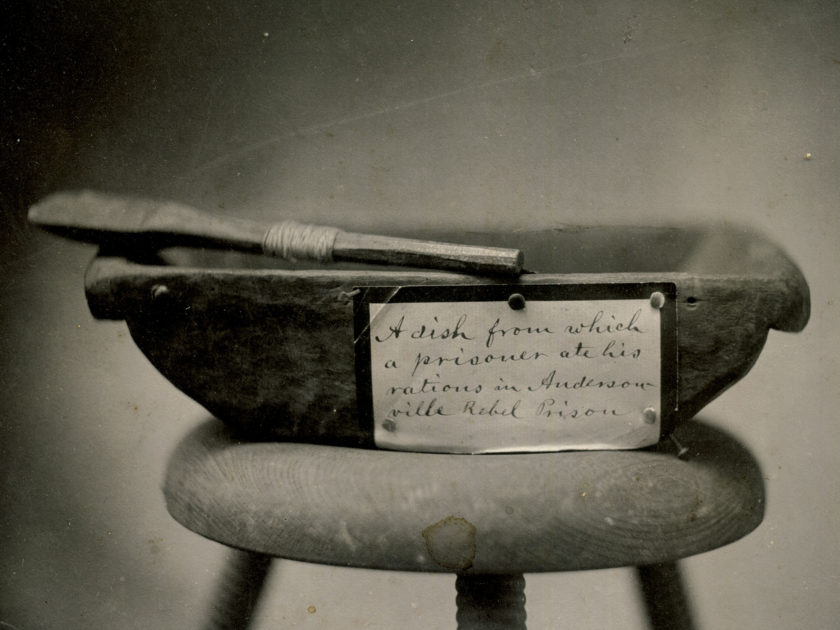

Each day of confinement as a prisoner of war became a struggle for life or death. Crude objects such as this sustained a soldier through his ordeal at Andersonville. Some 30 years later, a photographer documented the intrinsic value of this relic. With light and lens he transformed the hand carved wooden dish and spoon of one Benjamin Honeywell into a work of art.

This well armed Hoosier trooper, left, posed with drawn revolver and brandished blade in front of a patriotic camp backdrop. His stylish hat complete with ostrich plume completes his natty appearance. He is Austin Mason, a sergeant in Company C of the 5th Indiana Cavalry.

How lucky were the tent mates of this soldier when the time came to transition to winter camp? The ax, sawhorse and carpenter’s square suggest that he was master hut builder.

When 1st Sgt. Henry C. Rowland of the 77th New York Infantry made his way to J.H. Young’s photography studio in Baltimore, evidence suggests he invested serious thought into what would be a lasting impression. Rowland posed with an Enfield short rifle with saber bayonet, a non-commissioned officer’s sword, rolled overcoat and blanket atop the knapsack, a tin cup, likely affixed through the haversack buckle strap, and new first sergeant’s stripes pinned on each arm. The last elements to complete this picture, a tin plate and eating utensil, sit at the ready on top of the nearby table. Rowland was promoted to first lieutenant on Christmas Day 1862, and suffered a wound in The Wilderness in May 1864. He survived the war and lived until 1906.

Although not certain of the backstory of this patriotic young lady, the inscription, “Your Little Laura,” leads one to believe that a wife may have sent the image to her husband at war. A letter from home could certainly make a soldier’s day, and one can only imagine the joy he felt when he first laid eyes on the palm-sized treasure. More than a century later, the image still makes a powerful first impression and a personal connection to each new viewer.

Shot through both legs during the May 27, 1863, assault on Port Hudson, La., Capt. Jedediah Randall of the 26th Connecticut Infantry refused help as he lay on the battlefield. He ordered his men to be taken care of first. Finally carried to a field hospital, he lingered for 13 days before succumbing to his wounds. His resolute pose, the draped flag he died defending, and a cast brass eagle speak to his patriotism and sacrifice.

Civil War wit and humor are on display as a pipe smoking dog dressed in a soldier’s overcoat and wearing an officer’s kepi sits before a tactics manual with his pen. The inscription is a pointed commentary on the selection process for white officers seeking promotion into the U.S. Colored Troops: “A Lieut. in the Corps D’Afrique who passed Casey’s board.” The carte was originally part of an album that included two soldiers of the 7th Connecticut Infantry.

A private from Company C of the 33rd New York Infantry literally supports the flag in this camp scene. His comrade sporting a wide-brimmed hat is just visible inside the tent. The regiment participated in the Peninsula Campaign, Antietam and Chancellorsville during its enlistment.

A soldier displays an essential element of his existence—the knapsack. Historian and MI Senior Editor Mike McAfee remarked upon seeing the image that he had read period accounts of soldiers placing a dowel or stick atop the knapsack to prevent it from sliding down the back while on the march. But this was the first instance he had observed it. Zaidel purchased the image of the unidentified soldier, and later discovered his identity: John Harrison Mills of the 21st New York Infantry. Mills suffered a leg wound at Second Bull Run in 1862, and ended his service on April 21, 1865, in Buffalo, N.Y. His last act in uniform found him standing guard at the head of Abraham Lincoln’s casket, as mourners paid their respects to the late President.

The timeless gaze of an artillery sergeant seated with his Model 1840 light artillery saber is captured with technical perfection in this example of the wet plate photographic process. This image once belonged to legendary collector Herb Peck.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and mor