By Ron Field

The annals of the Civil War are replete with examples of youthful courage under fire. The best known in the army is Johnny Clem, the drummer boy who earned his sergeant’s stripes after he shot and killed a rebel colonel.

Perhaps the most extraordinary case in the U.S. Navy involves the son of an officer who managed to elude his parents and become an unofficial powder boy. James Vincent Johnston, all of six-and-a-half years old, assisted gunners on the Forest Rose during combat along the Mississippi River in early 1864.

How little Jim came to be aboard the gunboat and the events that led to his being christened “Admiral Johnston” is the stuff of legend.

Born in Cincinnati on Sept. 23, 1857, Jim owed his introduction to a sailor’s life to his father, John, a veteran riverboat man who owned and operated a packet steamer.

Recruited in late 1861 for the War Department’s new fleet of ironclad gunboats, John Johnston served a brief stint on the Benton before being transferred to the St. Louis. He ably commanded a section of that vessel’s great guns during the Feb. 6, 1862, bombardment of Fort Henry along the Tennessee River.

Johnston added to his laurels a couple months later in a daring night amphibious mission at Madrid Bend, part of the Mississippi River defenses of Confederate-held Island No. 10. On the night of April 1-2, he climbed aboard one of five navy cutters filled with sailors and Hoosiers from the 42nd Indiana Infantry, and participated in spiking the six guns of Battery No. 1. He captured the national flag of a Louisiana Artillery company, which he found abandoned along the riverbank, and suffered a minor wound at the hands of Confederate reinforcements that had arrived too late to save their guns.

Johnston’s gallantry resulted in a promotion to acting volunteer lieutenant in August 1862 and an appointment as executive officer of the St. Louis, which by this time had been renamed the Baron De Kalb.

Meanwhile, the Navy suffered a shortage of officers with riverboat experience. Johnston proved invaluable throughout the next year, as senior leadership moved him into several temporary commands aboard smaller gunboats, including the Forest Rose.

In February 1864, Johnston commanded the vessel. His wife, Eliza, with little Jim in tow, had joined him for a visit as no hostilities were anticipated. But while on a routine patrol along the lower Mississippi on February 14, a call went out to the Forest Rose to aid a Union battalion under attack by a Confederate brigade.

The action occurred at Waterproof, a town situated on the west bank of the river about 95 miles south of Vicksburg, Miss. The federal garrison, about 200 soldiers from two U.S. Colored infantry regiments, the 2nd Mississippi and 11th Louisiana, guarded a cattle depot. The Confederates, composed of three cavalry regiments and two rifled guns under the command of Col. Isaac F. Harrison of Louisiana, numbered about 800.

Harrison’s advance drove in the Union pickets, killing three and wounding one. The officer in charge, Capt. Joseph M. Anderson, found great difficulty in controlling his command and called for assistance.

Fortunately, the Forest Rose was not far off Waterproof and Johnston quickly got his vessel underway and commenced shelling the enemy. The Confederates fell back under cover of woodland, and maintained a steady fire on the gunboat for several hours. About 8 p.m., the rebels launched a further attack on Waterproof, but the Forest Rose repelled the assault.

The action resumed the next day when rebel reinforcements composed of two regiments of infantry and a battery of light artillery arrived. The Union troops held off the rebels and forced them to withdraw, due in part to the accurate firing from the two 30-pounder rifles and four 24-pounder smoothbores on the Forest Rose.

In an attempt to keep his wife and son out of harm’s way, Johnston confined them to his cabin. According to one report, Johnston “directed his wife to lay down on the floor in the cabin, tied Jim to the leg of a table and went about his duties. The little fellow did not propose to be a prisoner while there was a fight on. He soon freed himself and ran down to the gun deck.”

At one point, when a powder boy serving one of the guns was killed, Jim took his place and passed powder boxes from the magazine to the crew. Johnston happened upon his son, blackened and begrimed from the dirty and dangerous work, in the heat of the action and confronted him. Jim responded, “Why, Tommy (a young colored seaman) had his head shotted off over there, an’ I’m a-carryin’ his powder.”

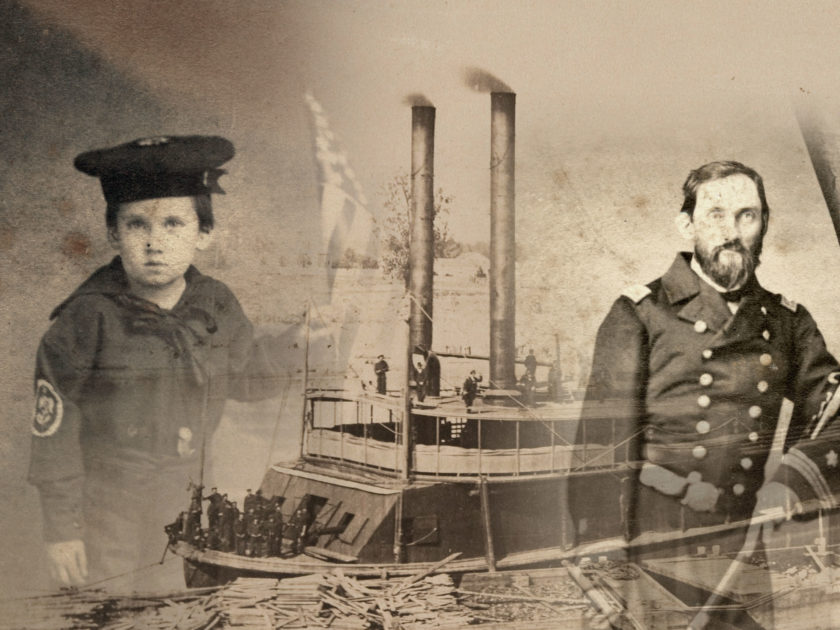

Johnston’s response was not recorded. But the crewmen of the Forest Rose hailed the boy as a hero. They presented Jim with a sailor suit, perhaps the same shown in this carte de visite portrait, and the nom de guerre “Admiral Johnston.”

A few months later, in June 1864, Johnston resigned from the navy. He spent the rest of his days in St. Louis, where he became commander of the Admiral Foote Naval Veteran Association. He lived until 1912. The Navy recognized his military achievements during World War II by naming two destroyers in his honor.

Little Jim grew up and married twice. He and his first wife, Annie, divorced in 1901, leaving their 18-year-old son James, Jr., to choose sides. He remarried in 1904, and died two years later from typhoid at age 48.

Several newspapers marked his death, claiming him as the Civil War’s youngest veteran.

Note: The War Department later designated the 2nd Mississippi Infantry as the 52nd U.S. Colored Infantry and 11th Louisiana Infantry as the 49th U.S. Colored Infantry.

References: 1860 Census; Weekly Herald, New York City, Feb,. 25, 1854; Memphis Daily Eagle and Enquirer, Jan. 2, 1855; Cincinnati Commercial Tribune, Jan. 30, 1862; Official Records of the War of the Rebellion; Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies; Daily Dispatch, Richmond, Va., May 27, 1904, and Feb. 5, 1905; Mobile Register, Mobile, Ala., April 6, 1862; The Age, Philadelphia, Pa., May 17, 1864; Col. John W. Emerson, “Grant’s Life in the West and his Mississippi Valley Campaigns (A History),” Book III, Chapter 36, Midland Monthly Magazine, Vol. X, (July-December 1898); “Memorial Sketch of James Vincent Johnston,” 1906. Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States. Commandery of the State of Missouri. Records, Missouri History Museum Archives, St. Louis; Cincinnati Daily Enquirer, Sept. 7, 1864, Evening Bulletin, Maysville, Ky., Sept. 11, 1895; San Francisco Chronicle, Feb. 20, 1906; St. Louis Star and Times, April 23, 1912; Leavenworth Times, Leavenworth Kansas, Feb. 27, 1906.

Ron Field is a Senior Editor of MI.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.