By Ron Maness

The standard by which all Congressional Medal of Honor recipients have been considered has remained consistent since its infancy during the Civil War. In essence, the tribute cites conspicuous acts of courage above and beyond the call of duty in the face of the enemy. A rigorous process to validate valorous actions and approve nominations, however, evolved over the next half century.

During the postwar period, additional recipients were honored, while others were called into question. In 1916, a Congressional review board formed to investigate and report on past awards led to Congress striking 911 names from the rolls.

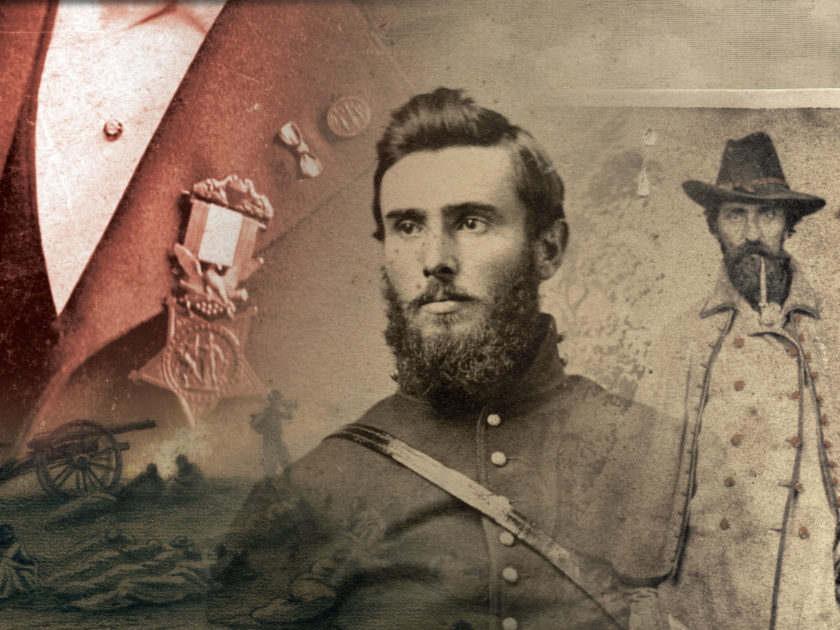

Here, we examine two Civil War events that reflect the lack of validation of the Medal of Honor and two largely forgotten men; One recognizing the integrity of the Medal above others, and the other, who never received it but was a hero beyond another in his regiment who received the recognition.

Honor Defined: Col. Mark F. Wentworth

Edwin Stanton pulled out all the stops to counter a real and present danger in the face of the Confederate invasion in June 1863. The harried, bespectacled Secretary of War worked every political and military channel to protect the Union from an uncertain fate.

One of Stanton’s flurry of moves occurred on June 28, 1863, a dire day for the North. Gen. Robert E. Lee and his rebel forces had advanced across southeastern Pennsylvania and threatened the state capital in Harrisburg. The opposing army had a new commander in his first day on the job—George G. Meade. He replaced Maj. Gen. Joe Hooker. The Army of the Potomac was still smarting from Hooker’s indecisive leadership and its ineffective performance nearly two months earlier at the Battle of Chancellorsville.

In Washington, Stanton reached out to Daniel E. Somes, a former Congressman who had represented Maine and who remained in the nation’s capital. Stanton asked Somes to use his influence to convince two Pine Tree State infantry regiments just about to muster out of the army to remain in uniform until the emergency passed.

The regiments had spent the majority of their 9-month enlistments in the defenses of Washington. Somes failed to persuade one of regiments, the 25th, to remain. He had better luck with the other, the 27th, thanks to Mark Fernald Wentworth, its 43-year-old colonel.

Wentworth enjoyed a sterling reputation. Born and raised in Maine, he practiced medicine in Kittery, a coastal town not far from Portsmouth, N.H. He also served as chief clerk to the naval storekeeper at the Kittery Naval Yard. In 1854, he organized a militia company, the Kittery Artillery, which he commanded as as captain.

Then, war came. In In the autumn of 1862, Wentworth bid his wife and three children farewell and left with his comrades in the newly formed 27th for Washington. He began his service as lieutenant colonel and second-in-command to Rufus Tapley, a prominent lawyer with no prior military experience. Tapley’s tenure ended prematurely with his resignation in the wake of a scandal that involved his brother, William, who Tapley had appointed quartermaster sergeant of the 27th, facilitating kickbacks from the regimental sutler that landed in the colonel’s pocket. Apart from this scandal, Tapley lacked military etiquette and motivation. A Board of Examination allowed Tapley to resign with some respect, and Wentworth was promoted to colonel.

Meanwhile, the regiment bade its time in Washington and never fired a shot in anger. It did, however, lose one man to the accidental discharge of a musket, and 19 more to disease.

On June 28, 1863, only two days remained in the regiment’s enlistment when Wentworth received the request for it to remain on duty beyond the conclusion of its term.

The next day, Stanton upped the ante in the form of General Order No. 195. It stated, “The Adjutant General will provide an appropriate Medal of Honor for the troops who, after the expiration of their own term, have offered their services to the Government in the present emergency; and also for the Volunteer troops from other States that have volunteered their temporary service in the States of Pennsylvania and Maryland.”

Wentworth managed to persuade about a third of his 864-man command to remain in the defenses—between 296 and 315 soldiers. The rest, about 550 men, boarded a train and headed back to Maine on July 1, as the Battle of Gettysburg unfolded.

Another who remained, 10-year-old Tom Murray, had escaped slavery and attached himself to the colonel. A few days after the Confederate defeat at Gettysburg, Wentworth and his volunteers were discharged, and soon reunited with their less patriotic comrades in Maine. Murray rode with them and found a home with Wentworth’s family, who raised him to adulthood.

Wentworth and a number of his fellow veterans returned to duty with the 32nd Maine Infantry, the last regiment raised in the state. In May 1864, it joined the Army of the Potomac on the Overland Campaign. The 32nd fought hard at The Wilderness, Spotsylvania, Cold Harbor and the Siege of Petersburg.

Wentworth remained at the head of his command until the July 30, 1864, Battle of the Crater. As one of the few colonels to enter the massive hole blown out of the rebel entrenchments, he led the decimated ranks of the 32nd in the fateful attack. At one point during the chaos and confusion, Wentworth paused to reform his men. His biographer recounted what happened next: “Just as Colonel Wentworth had given the order, ‘Forward,’ amid a fierce shower of bursting shells, he was seriously wounded, a bullet passing entirely through the left side of his body, having already, in its course, clipped off the arm of his comrade, Sergt. Ray P. Eaton. Wentworth, having received yet a second chest wound, was rescued from the enemy’s lines with great difficulty, and the escape of himself or any of his companions has always been regarded as quite miraculous. The colonel was unceremoniously rolled down an embankment and ‘dumped’ into the Union entrenchments.”

The biographer added, “Wentworth was tenderly carried to Maine, but his wounds were so serious as to render it imprudent for him to continue in the service.”

Wentworth resigned in November 1864, and later received the brevet rank of brigadier general of volunteers for his war service. He carried a Confederate slug in his body for the rest of his life.

Before his death, Wentworth made secret arrangements to dispose of the remaining Medals in his possession. To this day the Medals, believed to number in the hundreds, remain unaccounted, despite the treasure hunting expeditions.

In early 1865, as Wentworth convalesced at his home in Kittery, a letter arrived from Maine Gov. Samuel Cony. The governor reported he was in receipt of 864 Medals of Honor from the War Department in fulfillment of the general order. Each carried the inscribed name of a 27th veteran.

In this case, the War Department used the Medal as an incentive. Others were issued for reasons beyond the scope of battlefield courage. They included 29 soldiers that attended the Lincoln funeral train, and four awarded to civilians.

The task of distributing the 864 Medals fell to Wentworth. He might have taken the path of least resistance and presented all of them. He however opted to reconstruct a list of all the members of the 27th who stood by him—and the country—in July 1863.

Wentworth likely called upon his memory of his service with the 32nd, which had provided him an opportunity to experience firsthand battlefield valor and gallantry.

Still, the job proved challenging. Wentworth found that the records lacked enough information to accurately determine the soldiers that had remained in ranks. He eventually resolved a list of 299, and distributed the Medals to those men, and returned the balance to the State Capitol. Some years later, a subsequent administration returned the unawarded Medals to Wentworth. He stored them in a stable on his property.

Meanwhile, tensions mounted between recipients and non-recipients at regimental reunions. At some point the have-nots learned of the existence of the extra Medals. A break-in occurred at the stable, and many Medals went missing. Some of them showed up in the possession of veterans at later reunions.

Wentworth died in Kittery after a fall in July 1897 dislodged the bullet near his heart that had remained in his body since Petersburg—almost 33 years.

Before his death, Wentworth made secret arrangements to dispose of the remaining Medals in his possession. To this day the Medals, believed to number in the hundreds, remain unaccounted, despite treasure hunting expeditions.

Even in death, Wentworth stood steadfast as a guardian of the integrity of the Medal. Whether the colonel’s military service with the 32nd informed his decision to restrict the Medal to the relatively honored few who earned it may never be known. Still, Wentworth remains a pivotal and under-appreciated figure in the Medal of Honor story.

Honor Unsung: Pvt. Isaac L. Peirce

During their 1907 reunion, veterans of the 2nd Ohio Cavalry addressed a Medal of Honor controversy that involved their regiment. The dispute stemmed from an account by one of their own, Isaac Gause of Company E, in his soon to be released memoirs, Four Years with Five Armies.

The veterans got wind of the book after its publisher had written them with a request for photographs. A draft copy followed. In it, the veterans read Gause’s account of how he received the Medal of Honor for the capture of a Confederate flag near Winchester, Va.

Gause’s book recounted how he and his comrades clashed with elements of the 8th South Carolina Infantry during a skirmish along Abraham’s Creek on Sept. 13, 1864. As his story goes, the Ohioans charged the South Carolinians and received a volley that forced them back in disarray. One bullet knocked Gause’s carbine from his hand. In that moment he saw an opportunity to renew the attack and rallied his fellow troopers. “I shouted, ‘For God’s sake, men, do not let them get away, now we have them surrounded and they must surrender!’ A firm voice shouted, ‘Gause, we will follow you!’”

Off they went and charged again. The rebel infantry, positioned in a ravine, responded with another volley. This time, the troopers did not falter, and descended upon them before they could reload and fire. Gause remembered shouts of “Stack your arms! Surrender!” as the helpless rebels abandoned the fight. “I then dismounted, ran into the woods, took the flag, and marched the prisoners out.” Reportedly 16 officers and 145 men were captured.

Gause added with a flourish, “The prisoners marched up the ravine, and when they turned over the ridge I reined to one side and passed them. The Colonel saluted his flag and the men said, ‘We have followed it many times.’ ‘Under very different circumstances,’ was my reply.”“Flash forward to the 1907 reunion. Many of the veterans in attendance learned for the first time that Gause had received the Medal of Honor—and they rejected his claim.”

Flash forward to the 1907 reunion. Many of the veterans in attendance learned for the first time that Gause had received the Medal of Honor—and they rejected his claim. Maj. Albert C. Houghton investigated Gause’s claims and summarized his findings: “The account of what he [Gause] did comprised substantially all that was done that day, yet it was all so fantastic, so grotesque as to be ludicrous, and not likely to be taken for the truth by any one—certainly not by the fighting boys of the Second who were on that reconnaissance.”

The veterans questioned how Gause could have been present to capture the flag. They determined that Company H presided over the surrender of the Confederate force, and that Gause and his Company E occupied another part of the field. Many theorized that the South Carolinians had simply left the flag on the ground, and that Gause had otherwise picked it up as from a “brush heap.”

The veterans were further rankled to learn that Gause personally registered the flag as a trophy of war in Washington on Sept. 19, 1864. On this date, they were busy fighting for their lives in the Third Battle of Winchester, also known as Opequon. This engagement occurred after a week of scouting operations along Abraham’s Creek and elsewhere, unaccompanied by Gause.

During the reunion, the veterans resolved a motion to correct the record and request an investigation by the Secretary of War. The motion was later stayed after two veterans of Company E reported that Gause was insane and living in an asylum. The veterans deferred, taking pity on his situation.

Gause’s Medal of Honor remains in the official record. His citation states “Capture of the colors of the 8th South Carolina Infantry while engaged in a reconnaissance along the Berryville and Winchester Pike.” It is one of 256 generically worded citations that provide no formal documentation of the courage associated with the act.

In context, standard flag capture citations represent slightly more than half of all 467 citations that involve the capture of enemy colors. Considering the grand total of 1,199 Medals of Honor awarded during the war to soldiers (another 324 were awarded to sailors and Marines), the 256 generic flag mentions compose 21 percent of army citations, or one of every five recipients.

The 1907 scrutiny of the Gause citation brings into question the measure of courage involved with the other 255 flag captures. While the veterans of the 2nd Ohio challenged Gause’s claims, they also recognized a young man as “one of our most gallant comrades,” who happened to be the only trooper who died as a result of the skirmish at Abraham’s Creek—Sgt. Isaac L. Peirce of Company B.

What made Peirce special that he would be remembered 43 years after his death?

A native of Medina, Ohio, in 1839, he ranked the eldest son of 10 children born to Lorenzo and Emilene Peirce. Growing up on the family’s 170-acre farm, young Peirce developed an appreciation for horses. His passion may have inspired him to join the cavalry after the war began. In the summer of 1861, then 21-year-old Peirce enlisted in the 2nd. Surviving letters document his experiences in the saddle.

On Dec. 7, 1861, he wrote that soldiers and horses traveled on separate trains from Cleveland to Camp Dennison near Cincinnati. Peirce opted to ride with the horses. In the same letter, he reported that he and two comrades, William Mansfield and Lyman Judson, had gone out for a joy ride on their mounts. “If I was at home and rode so I should expect to get my neck broke,” acknowledged Peirce.

Five months later the trio had another adventure that ended in tragedy—and proved Peirce’s valor. On May 7, 1862, Peirce, Mansfield and Judson foraged with eight other troopers along Horse Creek in Barton County, Mo., when they suddenly encountered 60 enemy cavalry commanded by Capt. Sidney D. Jackman.

The 11 Ohioans fled in the face of superior numbers. A Confederate pursuit ended with seven Union casualties, including Mansfield, who died, and Judson, who fell into enemy hands, along with two others. Peirce and three of his comrades escaped without injury.

Capt. Jackman and his troopers left with their three prisoners. A few days later, one of the captives, a Sgt. Smith, managed to convince Jackman that he be released in a prisoner exchange. Jackman agreed, and Smith rode through western Missouri, crossed into Kansas and made his way to Fort Scott, where the 2nd had been stationed.

A lieutenant in the 2nd recalled what happened next in a letter published in an Ohio newspaper, the Painesville Telegraph: Smith “made his way into the fort in good order, but unfortunately was taken ill about the time his parole expired. In this dilemma Sergeant Isaac Peirce volunteered to return to Jackman in Smith’s place and effect the exchange. A lonely journey over the prairie in those days meant a great deal—the chances being that a man’s body would bleach in the long grass before he was washed for the ceremony. Sergeant Peirce made the trip, effected the exchange, and returned to camp without the loss of a hair.”

Peirce in fact rode all the way to Maysville, Ark., to find Jackman—a 110-mile trek across challenging terrain—and fulfilled his obligation. Such was his moral fabric.

A new challenge presented itself soon after Peirce returned to Fort Scott. The regiment’s Ohio bred horses could not survive a diet of prairie grass, and the number of animals shrunk to about 250. The resourceful Peirce acquired a Plains mustang from Union-friendly Indians in Kansas and named him “Pony Mack.”

The following summer, Peirce likely rode the mustang in operations to capture Confederate Gen. John Hunt Morgan and his troopers during their bold raid into Indiana and Ohio. Peirce and his comrades covered nearly 1,000 miles over the course of a week in the successful pursuit of the enemy. Reports place Peirce at the surrender of Morgan, which occurred in Ohio at Buffington Island on July 19, 1863. Afterwards, the Ohioans were rewarded with a 10-day furlough. It is believed that Peirce, on Pony Mack, headed for home, and left the mustang with his family when the time came for him to return to duty.

Less than a year later, Peirce’s luck ran out along Abraham’s Creek, when a rebel bullet struck him in the left hip during the apex of the charge toward Winchester. He succumbed to his wound on Sept. 14, 1864, the day after the skirmish.

Maj. Alvred B. Nettleton of the 2nd announced the death to Peirce’s father. “God knows it pains my heart to be the bearer of such ill tidings, but be apprised that Isaac’s home friends are not the only suffrers (sic) by his untimely death. Many a brave soldier’s cheek is wet this morning with tears for your noble boy.” Nettleton added, “In the deepest of your grief you have reason to be proud of the heroic bravery of the noble son you have given up for the life of the nation.”

Though Peirce never received the Medal of Honor, he forever earned the respect of the regiment. His remains reside in a hero’s grave.

Special thanks to Myrna and Joe Cagnina, descendants of Isaac Peirce, who have graciously offered the images of Isaac and Pony Mack.

References: Gause, Four Years with Five Armies; Houghton, 1907 Reunion—Reconnaissance of Abraham’s Creek; Chester, Recollections of the War of the Rebellion – A Story of the 2nd OVC; Jackman, Behind Enemy Lines; Hunt, Colonels in Blue – The New England States (Tapley); Pullen, A Shower of Stars; Schmutz, The Battle of the Crater.

Ron Maness has researched the Civil War for more than 50 years. His primary research topic is the Ames Manufacturing Company and their pre-war operations. Having no known Civil War ancestors, Isaac Peirce and Mark Wentworth have been adopted.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.