Introduced by John Banks

On nearly every step upon a Civil War battlefield, history, tragedy and spirits tug hard on the imagination.

But perhaps none more so than at Antietam.

Because this hauntingly beautiful battleground appears much as it did more than 150 years ago, we don’t need great inventiveness to envision the horror of Sept. 17, 1862—the day Americans slaughtered each other in unprecedented numbers near Sharpsburg, Md.

At Burnside Bridge, where mist often hovers low over Antietam Creek early in the morning, we can easily envision the carnage at a place a hospital steward in the 11th Connecticut Infantry called “a creek of death.”

In the Bloody Cornfield—once “reddened with blood and torn by bullet and shell,” according to a Massachusetts soldier—only battlefield monuments and a park road have greatly altered the long-ago landscape.

In the 40-acre Cornfield, we can walk the same desolate, hilly ground described by a Union soldier after the battle as a place where “heroes rest side by side & only a plain board, marked with name, Reg., Co. and date of death are the outside decoration.”

At Confederate Gen. James Longstreet’s headquarters in Henry Piper’s house—where a farmer’s daughter was horrified to discover a dining room full of dead soldiers after the battle—little has changed.

More than a decade ago, a battlefield visitor sat on the porch there and watched as fireflies lit up a field near Piper’s modest home. “We like to think the souls who fought here,” a local said of Mother Nature’s light display, “are still among us.”

Perhaps that’s why the portraits of Antietam soldiers on these pages stir our souls today. With a little imagination, we easily can take a step closer to them.

After the Long March

The division of Confederate Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws arrived on the battlefield on the morning of Sept. 17, weary and exhausted after rapid and long marches from Harpers Ferry. The division’s number included 22-year-old Sgt. John C. Lowe, opposite, of the 13th Mississippi Infantry. He and his comrades were soon called to support troops in the West Woods, and, though weakened in numbers due to fatigue and straggling, they held their own. During the action, a Yankee bullet tore into Lowe’s left arm and at some point his shattered limb was amputated. Lowe was left behind the next day after the Confederates withdrew, and he fell into Union hands. His captors paroled him soon after, and he made his way to Richmond, and then on to his home in Mississippi. Lowe received a discharge in April 1863 and died in 1920. He outlived his wife. A daughter survived him.

The division of Confederate Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws arrived on the battlefield on the morning of Sept. 17, weary and exhausted after rapid and long marches from Harpers Ferry. The division’s number included 22-year-old Sgt. John C. Lowe, opposite, of the 13th Mississippi Infantry. He and his comrades were soon called to support troops in the West Woods, and, though weakened in numbers due to fatigue and straggling, they held their own. During the action, a Yankee bullet tore into Lowe’s left arm and at some point his shattered limb was amputated. Lowe was left behind the next day after the Confederates withdrew, and he fell into Union hands. His captors paroled him soon after, and he made his way to Richmond, and then on to his home in Mississippi. Lowe received a discharge in April 1863 and died in 1920. He outlived his wife. A daughter survived him.

“Forever Green Shall Be Their Memories”

Capt. Mervin Eugene Cornell of the 102nd New York Infantry died after a Confederate sharpshooter’s bullet penetrated his skull. According to the after-action report by his lieutenant colonel, James C. Lane, Cornell fell early in the morning as he formed his command in a line of battle.

His newspaper obituary told another version of the story. It observed that Cornell, a conspicuous target in full dress uniform, advanced with his men when rebels attacked the other three regiments of their brigade. Chaos ensued. “Capt. Cornell, with a quick eye, seeing the crisis, threw himself to the front, waved his sword and called to his men, ‘Don’t falter; don’t fall back. Come on boys, follow me,’ and thus – ‘foremost fighting, fell.’” The report continued, “A rebel bullet pierced his brain, he threw up his arms, reeled, fell in the arms of one of his men, who sprung forward to receive him, and died without a groan. The brigade rallied, drove the rebels from the wood and beyond and held the ground thus gallantly won.” Cornell’s comrades dug a shallow grave with their bayonets and buried his body. His family later recovered the remains.

The sentiment at the end of the obituary spoke for many a fallen warrior. “How bravely, how gloriously did this young soldier die, throwing himself fearlessly into the very jaws of death, that he might turn the tide of battle. Laid himself upon the sacrificial altar of his country, a willing offering for her salvation. When the record shall be made up, what boon shall requite the sacrifices of such young hearts. Forever green shall be their memories, and the richest measure of their country’s glory shall be theirs. And amid the brilliant and cherished galaxy, sparkling with such names as Lyon, Winthrop, Ellsworth, Baker and young McCook, not the least shall be the name of Mervin Eugene Cornell, who thus gallantly gave his young life for his country upon the bloody field of Antietam.”

Twenty-One Holes

As rebel infantry in the Cornfield opposite him fired away, Capt. William Sterling King paced the line of his 35th Massachusetts Infantry and directed fire. King, acting major of the regiment, paused at one point, picked up a gun, and fired it. His comrades cheered. The enemy fire increased and the Bay State boys returned fire as ammunition ran low. With no supplies or reinforcements in sight, King and others tore open cartridge boxes from those who would no longer need them and distributed whatever ammunition remained.

As darkness set in, musket flashes lit up the battle line. The brightness of the Confederates fire made it clear that the 35th must fall back. By this time, King had been struck numerous times and was assisted from the field with the colors.

A newspaper report described the extent of his injuries: “There being twenty-one holes in his clothing, made by shot and shell, seven of which took effect on his person, one bullet hitting him in the leg, which was afterwards extracted; one in the fleshy part of his thigh; one, the most severe, in the shoulder, a minie ball entering at the collar-bone in front; one on each side of the spine, making deep flesh wounds; one passing just above his ear, raising a blister as it passed; and a piece of shell hitting him on the head, making a severe wound.”

Miraculously, King survived. “For four months I struggle for life, a portion of the time against hope; but the buoyant heart, with God’s blessing, bore me through,” he recalled.

King went on to serve as colonel of the 4th Massachusetts Heavy Artillery, and he performed staff duties on the division and district level. At the war’s end, he received the brevet rank of brigadier general. King returned to Massachusetts, became a civic and political leader, and lived until 1882. He died at age 63 having outlived his four children. His wife, Ellen, survived him.

“I Think I Die In Victory”

If the story of a battle could be written in vignettes, Lt. Col. Wilder Dwight’s Antietam experience would include four.

One pictures Dwight on horseback, riding along the line of his 2nd Massachusetts Infantry displaying the captured colors of the 11th Mississippi Infantry as his men responded with cheers and the enemy with bullets.

Another view shows Dwight lying on the ground, alone and abandoned, bleeding from wounds in his hip and arm. While he waited for help, he finished a letter to his mother started earlier in the day. “Dearest mother, I am wounded so as to be helpless. Good bye if so it must be. I think I die in victory. God defend our country. I trust in God & love you all to the last. Dearest love to father & all my dear brothers. Our troops have left the part of the field where I lay.”

A third reveals the regiment’s assistant surgeon, Dr. Lincoln Stone, and a few enlisted men recovering Dwight, and carefully carrying him from the field.

The final vignette presents a plucky Dwight putting on a brave face in front of his men after his rescue, noted an historian. “‘Mind, I don’t flinch a hair!” said he, while lying on a stretcher; sending the surgeon to relieve the wounded lying around, or telling his attendants to give water to the thirsty men; calling the drum corps to play ‘The Star-spangled Banner’ once more, next day; and asking to have the Flag waved again before his dying eyes.”

Dwight succumbed to his wounds on September 19. His remains were transported from a hospital in Boonsboro, Md., to Baltimore, where the body was embalmed and sent via New York City to Boston. There, a large group of family and friends, including fellow Harvard graduates, paid tribute to his sacrifice.

“Glorious But Melancholy Exhibit”

The editor of the Semi-Weekly Standard of Raleigh, N.C., included a warning when it printed the after-action report of the 3rd North Carolina Infantry at Antietam. “The official report of the casualties,” noted the editor, “have been handed us for publication. It is a melancholy but glorious exhibit.” What followed was a list of names that ran more than a half column. Among the casualties was the officer pictured here, 1st Lt. William R. Gaylard. At some point during the battle, likely in one of the savage charges made by the regiment in the Cornfield, a bullet shattered his left kneecap.

Gaylard, 23, was one of the original members of Company I, which had formed in 1861 in Beaufort County, N.C., as the Jeff Davis Rifles. He started as third lieutenant and advanced to first lieutenant by July 1862.

Two months later at Antietam, he suffered the knee wound. He and fellow members of the 3rd hold the grim distinction of having suffered the greatest total loss of any regiment during the bloodiest single-day battle of the war. It entered the engagement with 520 men and lost 330—most in the short space of an hour.

Gaylard escaped safely from the battlefield, but his combat career was over. He resigned in April 1863 due to a stiffened leg that required the use of crutches for the rest of his days.

The Iron Brigade Lives Up to Its New Nom de Guerre

The Iron Brigade, as the story goes, received its nom de guerre during stubborn fighting at the Battle of South Mountain on Sept. 14, 1862. Yet, just a few days later at Antietam, the brigade composed of four Western regiments—three from Wisconsin and the 19th Indiana Infantry, along with the 4th U.S. Light Artillery—made the name revered.

One of the soldiers in the ranks, John Hastings, served as a private in the 19th. He and his fellow Hoosiers occupied the far right at Antietam. During the fight, the men made a determined charge with bayonets that ended with a devastating volley from an enemy brigade. It was likely here that Hastings suffered a severe wound that shattered his left elbow.

A surgeon performed battlefield surgery to remove bone fragments. A second surgery soon followed, and a unique wire splint was applied to stabilize the limb. Doctors documented the procedure and the months of treatment that followed, and published the case in the landmark series Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion. Though the surgeons ultimately avoided amputation, Hastings could not use his arm for any practical purposes and suffered permanent disability.

Hastings received a discharge for his wound in February 1863 and watched from the sidelines as his Iron Brigade further distinguished itself in other engagements through the rest of the war, including Gettysburg and Appomattox.

Hastings died in 1875 at about age 34. It can be justly stated that he contributed to, in the words of one writer, the “indomitable courage and unparalleled power of endurance” of the Iron Brigade.

First and Last Command

There came a moment early in the fight when the 15th Massachusetts Infantry deployed in line of battle and marched forward to an uncertain fate. One of its officers, Richard C. Derby, recently promoted from first lieutenant to captain, commanded Company C in combat for the first time.

It was his last.

Derby turned to one of his subordinates, 2nd Lt. Walter Gale, as they approached the enemy. He asked Gale to attend to the men on the company’s right while he covered the left.

Gale recalled what happened next: “In a moment heavy volleys were poured into our ranks, and finding myself slightly wounded I sought the shelter of a tree. While binding my wound, I saw the lieutenant cheering on his men in the most heroic manner; it was a scene that I never can forget. Two minutes later he also was laid at the foot of the tree, fatally wounded in the temple. He was quite unconscious, apparently in almost a childlike sleep; and thus, without suffering, he passed from life to immortality.”

His loss was a severe blow to all who knew him. The many outpourings of grief included this tribute from a friend, “Derby combined courage and patriotism with the polish of a gentleman, and the most prepossessing manners and form. He was rising rapidly in the army; and his death is a severe loss to his kindred, his many friends, and to the country.”

Human Cornstalks

Standing on a bluff overlooking Sharpsburg, the men of the 9th New York Infantry, or Hawkins’ Zouaves, paused to consider their tenuous position. They had marched through enemy fire, and were well in advance of any other Union unit on that portion of the field. Without support they could go no further. One officer in the regiment commented, “I glanced back at the field we had just crossed and saw it sprinkled all over with our dead and wounded, all lying with their heads toward the enemy, presenting the appearance of a thin field of cornstalks I had seen some place, all rolled down to lie in the same direction for convenience in plowing them under.”

Among the wounded was 21-year-old Pvt. James Hyer of Company E. Hyer was treated for his injury and sent to the general hospital in Chestnut Hill to recuperate. In January 1863 he received a discharge. He returned to his home in New York City, married twice and fathered four children. He worked as a railroad ticket agent until his death in 1892 at about age 51.

Battlefield Souvenir

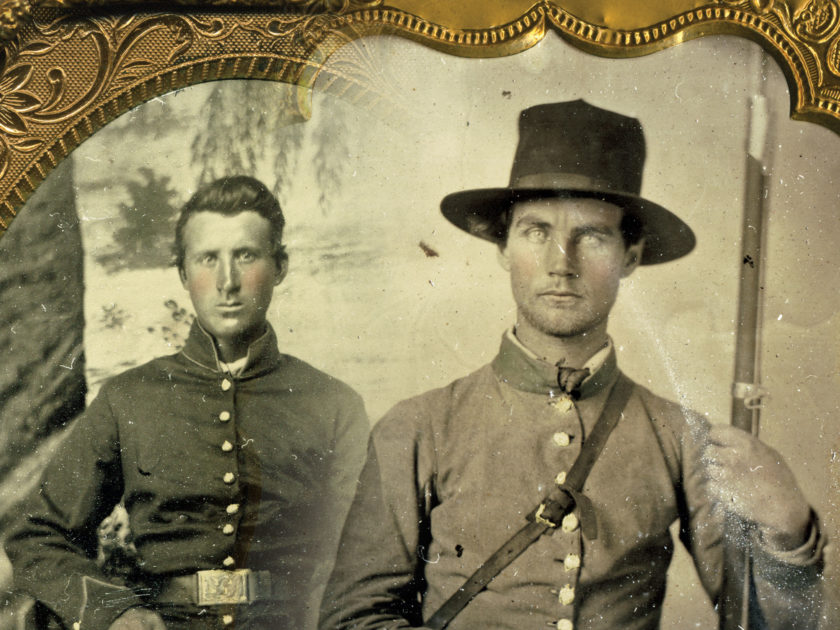

Exactly where and on which part of the battlefield the portrait above was found is unknown. But thanks to a note pinned to the case, we know who recovered it—Pvt. Ira A. Graham (left). He and his comrades in the 14th Connecticut Infantry were in the thick of the action at Antietam, their first battle. The regiment, which had mustered into federal service only a few weeks earlier, suffered heavy losses at the Roulette Farm and near the Sunken Road.

At some point, Graham picked up this battlefield souvenir. The young soldier pictured wears the distinctive jacket and belt plate of New York troops.

Graham went on to become a first lieutenant and served at the Battle of Hatcher’s Run on Feb. 2, 1865. During the fight, a bullet tore into his right chest and passed entirely through his body. He survived and returned home to Connecticut, where he married and started a family. Complications from the wound caused his death in 1869. His wife, Phebe, and 3-year-old son, Seager, survived him.

Battle Scar

Some of the survivors of the battle carried physical scars for life. Such was the case for Pvt. Tom Spaulding. He and his fellow soldiers in the 49th New York Infantry were in action most of the day and exposed to enemy artillery. According to the regiment’s official report, most of the casualties in the 49th were the result of shellfire. This post-war view suggests that a fragment struck him. Spaulding’s paper trail ended after the battle. It picked up a year later, when he rejoined the army as a private in the 8th New York Heavy Artillery, under the alias Jerome Spaulding. In this capacity, he suffered his second wound during the fighting at Cold Harbor in June 1864. He recovered from this injury, mustered out at the war’s end, and lived until 1908.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.