By Alison Renner

Had I been there, Aug. 8, 1861, the day Joseph Parsons joined the Union army, I might have bartered for his place. I might’ve pleaded with him not to enlist, to wait until he was drafted and relieve himself of the responsibility. Perhaps my maternal insistence could’ve compelled him to stay on the family farm in Baltimore County, Md., for another year, thus sparing him from his battlefield fate.

These are the fantasies that hindsight offers and they do nothing to protect young men. Still I would’ve liked to intervene, to save Joe from the sacrifice that befell him.

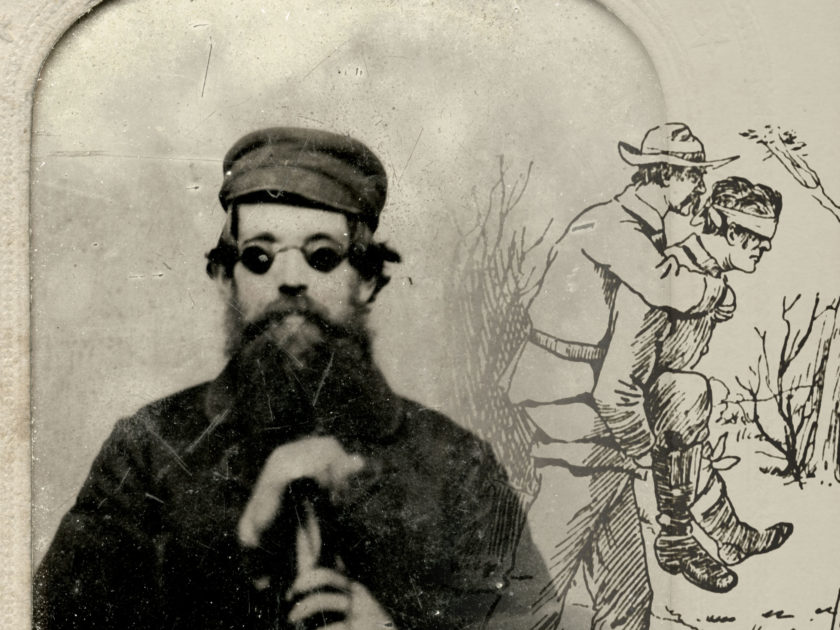

From my vantage point, roughly 150 years in the future, what I saw when I first laid eyes upon a tintype of Joe was his blindness. The tiny glasses that hid his physical trauma did not appear to be the entire measure of the man. He held a cane with a resigned comfort, but it was hardly the focus of the photo. He had a relaxed coolness about him that made him appear quite contemporary. He did not reflect the average sitter with a serious or stern expression. What was most noticeable about this anonymous blind man is that he appeared to be happy.

My husband, who had plucked the blind man from a stack of photos at an antique store, suggested we buy all the images, the negatives and ephemera surrounding the man identified only as “Uncle Joe Parsons.” It seemed like a solid investment and I had hoped to sell the blind man for a profit. Unbeknownst to me, Parsons arrived at our house with his entire family in tow. Moldy cartes de visite of forgotten children and family portraits filled our kitchen table. We wondered if they all might be related and if they had known Joe.

Grouped with the tintype of Joe was a folder filled with World War II era negatives, service records and more photos. It also contained what appeared to be personal mementos of a soldier named Hermann Brandmiller. His name sounded oddly familiar, but I had made these leaps before. I told myself that not every photo leads to a web of coincidence, nor is every subject of a Victorian era photo secretly whispering from beyond the grave to reveal his story. I let the name Brandmiller stew in the back corner of my memory, hoping to retrieve its relevance.

We had the luxury of some period handwriting on the reverse of the sealed tintype, but often that is not enough to conclusively identify an individual. I feared that was the case with the very common sounding “Uncle Joe.”

Though the name seemed ubiquitous, we dug into primary source material unsure of what lay ahead. We could not have anticipated the tale we uncovered by merely searching “blind” and “Joe Parsons” on Newspapers.com. My husband found it during an initial search and excitedly called me to read the tale of the blind soldier boy.

The story told by a correspondent for the Boston Transcript described a chance meeting with a young private blinded in battle who recuperated in a military hospital—Joe Parsons of the Union 1st Maryland Infantry.

The Transcript writer related, in the vernacular of a “young rough,” how a minié bullet blinded Joe in the brutal fighting at Antietam. He lay on the field overnight, badly wounded and unable to orient himself to his environment and flee to safety. He heard a voice call out in the darkness, so the story goes. It belonged to a Southern soldier who had been wounded in his leg and unable to walk.

Perhaps they could join forces and escape together. There was however, an impediment to their partnership. Just a day earlier they had been enemies. Had it not been for their predicament they might’ve remained so, but desperation makes strange bedfellows. In a moment, humanity intervened and opposition melted away. The sighted though maimed Confederate climbed onto Joe’s back and off they went through the darkness. Joe reportedly told the correspondent, “‘I did the walkin’ for both, an’ he did the navigatin’. An’ if he didn’t make me carry him straight into a rebel colonel’s tent, a mile away, I’m a liar!’”

No longer a threat to any soldier, the Confederates bandaged Joe, gave him a parole and sent him to the North. While Joe’s good deed won him his freedom, he had months of hospital treatment to endure. In one place, Judiciary Square Hospital in Washington, his cheerful disposition in the face of adversity attracted the attention of the Transcript correspondent looking for good copy. The published story ended with the correspondent talking to Joe:

“‘But you will never see the light again, my poor fellow,’ I suggested sympathetically. ‘That’s so,’ he answered glibly; ‘but I can’t help it, you notice. I did my dooty—got shot, pop in the eyes—an’ that’s my misfort’n, not my fault—as the ole man said of his blind hoss. But—‘I’m a bold soldier boy,’ he continued, cheerily renewing his song; and we left him in his singular merriment. Poor, sightless, unlucky, but stout hearted Joe Parsons.”

A couple weeks later, the correspondent updated readers on the situation, “Joe is entirely at liberty around the hospital—going and coming from ward to ward, all day, and about the grounds, outside, cane in hand, feeling his way to and fro, unmolested—and always uttering a pleasant word of encouragement to his sick and wounded companions, a song to himself, or a ready jest to visitors.”

It seemed unlikely to me that the photo of the blind man we had purchased could be the boy from this mythic tale, yet how could it not be? The facts were so similar. If this were indeed the same brave soldier, why would that fact not be reflected in some notation in the family’s volume of photos? Certainly a newspaper article would accompany his photo in the family archives.

Though my innate skepticism prevents assumptions not bolstered by concrete facts, I had a strong suspicion that somewhere in the darkness of 1862 a young man was whispering for his voice to be heard. Could this blind soldier whisper loud enough for me to hear him 150 years in the future? Could a lifetime of darkness be traded for a measure of immortality a century-and-a-half later? I resolved to trust my instincts.

Conveniently, Joe Parson’s story was the Victorian equivalent of viral. It appeared in major newspapers in the U.S. and abroad, reprinted and edited to suit the needs of an evolving readership. Slight changes in each retelling offered enough clues to begin my search in earnest.

“Joe Parson’s story was the Victorian equivalent of viral. It appeared in major newspapers in the U.S. and abroad, reprinted and edited to suit the needs of an evolving readership.”

One of the clues was that Joe Parsons hailed from Baltimore. Using census data, I tracked a young man of the same age and name from Baltimore to Atlanta, Ill. After finding a newspaper article about a blind horse trainer named Joe Parsons who hailed from the same Illinois town, I hoped this was the right trail. But it went cold. I eliminated his name from a list of possible Joes from the Baltimore area.

I turned back to family photos. The answer to Joe’s identity had to lie in this pile.

I fanned the images onto the kitchen table, looking with fresh eyes to these anonymous men and women, many Ohioans, hoping they would speak to me. The first connection I made was with Joe’s brother, his name barely visible in graphite on a gray mount. I dropped his information into a family tree I had started for Joe and was pleased to find his name matched a brother listed on the 1860 census of another Joe I had found—my “most likely Joe.”

Civil War historians who can identify the rank of a soldier in an instant amaze me. I liken it to a language, those clues held in uniforms and caps are a wholly different vocabulary. It’s a vernacular I do not speak. However, in my own field of research, that of Victorian sideshow circus performers, I can often identify albino mind readers by a recurring string of pearls or a particular Circassian girl by her decorative hosiery. In the world of soldier identification, not unlike circus performer identification, the key is to notice the details until they become so commonplace that they can never be overlooked. Details are the language in which photos communicate with their observers. And I vowed to listen to all of them.

I mused that if Joe wanted me to pursue his story, he’d probably add some circus-related element into my search, which could propel me forward. Suddenly, it dawned on me why the name of the World War II soldier sounded so familiar. Herman Brandmiller and his wife, Elsie, were collectors and researchers of circus history. Their archives compose the Brandmiller circus collection at Miami University at Ohio.

I checked some back issues of the circus magazine White Tops from the 1970s. Among the classifieds was a half remembered ad from the Brandmillers wishing everyone in the circus community a Merry Christmas. Was this a message from Joe? A direct link between the Brandmiller and Parsons families would provide a union of the eldest and youngest people in the genealogy. I searched for a way to prove an ancestral relationship. While the Season’s Greetings later proved a valuable key to the puzzle, it was not the Rosetta Stone that would link the Joe Parsons in my photo to the Joe Parsons wounded at Antietam.

The connection was ultimately made by a circa 1890s photo of four sisters—the Evarts girls. They were adults at this point, some with married names of their own. Their birthdates and names were carefully preserved on the mount with a tender note to “Brother Reuben.” This touching, sentimental moment provided important biographical information that enabled me to complete the Parsons family tree. The Evarts sisters were the children of Reuben and Rebecca Evarts. The 1870 census of Belleville in Jefferson County, Ohio, lists Reuben, Jr. and his sisters living in the exact location of most of the photos in the collection.

In 1872, Reuben, Jr. married Annette J. Rhodes. The following year, a daughter Mary was born to the young couple. Two years later another daughter, Clara, entered the world. She married in 1895 and took on her new husband’s name—Parsons.

Her new husband is the nephew of one Joseph Parsons of Baltimore. Ten years later, in 1905, Clara and the nephew become parents to a daughter who they named Elsie. She grew up and married Herman Brandmiller in 1930. When Herman died in 2000, his personal effects were sold. A decade later, they showed up at an antique store on my block.

I now had established a direct line between Joseph and his family members. I am confident that this Joe Parsons is the brave, blind soldier boy.

What does one do with an obscure historical treasure? I told everyone with a passing interest in photography or history of Joe. I even dragged him to the Antiques Roadshow, but I didn’t know how to bring his story to the present time. My friend and fellow photo collector Nick Vaccaro put me in touch with Doug York of Civil War Faces. Doug suggested I meet with Military Images magazine editor Ron Coddington and himself in Gettysburg to discuss my findings.

Living in close proximity to the battlefield, I’ve visited Gettysburg nearly every year of my life. The site never fails to move me on an emotional level. It proved to be a perfectly appropriate site for me to reveal Joe to people who truly understood his importance. On the slightly sticky surface of a café table at the summer 2018 Civil War Artifact and Collectibles Show, I nervously revealed my newspaper clippings, detailed hand scrawled family trees, individual biographies and the photos of the Parsons family. I wished Joe’s mother could be there to watch us fawn over Joe, his sacrifice and his legacy. His presence loomed large that day. I wondered if somewhere in the ether Joe could see us beaming.

I found a research ally in Ron, who quickly filled the gaps in my military knowledge. He vowed to aid my research with the tools at his disposal and immediately started working on Joe’s story. When he wrote to me a few days later and told me that no Joe Parsons was listed on the roster of the 1st Maryland Infantry my heart sank. It hadn’t occurred to me that the Boston Transcript story was anything less than 100 percent accurate. Had my love of the tale blinded me to its “fake news” potential? Could the story be entirely fabricated?

Reeling from the possible ramifications of this news, I returned to the facts. I knew from the 1870 census that Joe returned to Maryland after the war and resided in Wiseburg, a small town north of Baltimore near the Pennsylvania border. I drove to Wiseburg and perused the cemetery, intent on soaking in enough remnants of Joe’s life to aid the search.

Ron had also mentioned that three men with the name Joseph Parsons served in Maryland regiments in the Union army, according to the American Civil War Database (HDS). Two of them did not enlist until 1864. They therefore could not have been in uniform at Antietam. The third however, one Pvt. Joseph Parsons of Company F, 2nd Maryland Infantry, enlisted in 1861, more than a year before the battle.

I pinned my hopes on this being our Joe.

Acting on a hunch based on Joe’s gregarious nature suggested in the Boston Transcript story, I searched the newspapers closest to Wiseburg for a mention. In a story published on July 5, 1866, in the Democratic Advocate of Westminster, Md., a Joe Parsons gives a lecture to the Johnson Club in Baltimore County’s 6th District. This Joe, “well known as having lost both eyes in the Second Battle of Bull Run on the 30th of August 1862,” made a short speech detailing his desire for a truly United States. “Having fought for the Union, he now wanted union.”

This was the same Joe Parsons that had served in the 2nd Maryland Infantry. According to his military service and pension records, which Ron retrieved for me from the National Archives and Fold3.com, Joe was blinded by a bullet that passed through both eyes during the savage fighting near Brawner’s Farm, or Groveton, Va., better known as the Second Battle of Bull Run.

Joe never saw a glimpse of Antietam.

The military records revealed another crucial detail that had always eluded me. The reason I couldn’t find him in census records from 1900 or later became obvious, as he had died in 1885.

I scrutinized every detail in his pension file to learn more. Thankfully, Ron had sent me every page. Though it is sobering to read of a young man’s life reduced to monthly notations of whereabouts or descriptions of his horrific wounds, the medical and service records also bolstered Joe’s tale. He did have both eyes “shot out in one pop” and he suffered greatly, needing assistance for most tasks during the rest of his life.

Ron pointed out that Joe’s military service record included a document that stated he had been captured on the battlefield and paroled on Sept. 6, 1862, just eight days after his wounding. This corresponds to the Boston Transcript narrative. If his sighted partner guided him to a Confederate camp, as the story states, this would be the recorded proof of such an act.

The pension record revealed another fascinating detail. We were not the first researchers interested in Joe’s story. A circa 1913 letter from Dr. Burt Green Wilder was included in the envelope. It detailed the doctor’s desire to include Joe’s story in a book of Civil War era reminiscences. A staffer responded to Wilder’s request and shared with him the limited knowledge of Joe’s post-war life.

Dr. Wilder was very familiar with Joe’s case. He had been a medical cadet in the regular army at the time Joe suffered his wound and ended the war as surgeon of the African American 55th Massachusetts Infantry. Wilder’s diary, reprinted in part in the 2017 book Recollections of a Civil War Medical Cadet, details several interactions with Joe. Cadet Wilder recorded a surgery performed by Dr. Francis Henry Brown on Oct. 5, 1862, in his log book. “Parsons. Wound enlarged under ether and much comminution of orbit found; some small pieces removed.”

Armed with this knowledge, I’m confident more details will emerge about Joe’s story in the future. Perhaps one day we will learn the name of the anonymous Confederate, should he exist.

We may never know why the Boston Transcript correspondent incorrectly stated that Joe served in the 1st Maryland Infantry and suffered his wound at Antietam. It is possible that the writer never met Joe and was merely recording a story already embellished as it passed through the hospital wards. It is also possible that the correspondent knowingly added the flourishes. As a Northern reporter, it might make for a better story to relate Joe’s sacrifice to the Union success at Antietam (as President Lincoln did with the announcement of the Emancipation Proclamation) rather than the loss at Second Bull Run. And we cannot discount the thought that Joe exaggerated his own story.

Revealing the discrepancies in the reality of Joe’s tale versus the popular account makes it no less incredible. We now know that the bold soldier boy Joseph Parsons made it off the Bull Run battlefield and into myth.

Alison Renner is a photo collector and dealer with a particular interest in the stranger side of Victoriana. She is currently writing about sideshow photography in America’s first capital.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.