By Michael J. McAfee

Organized out of wartime necessity in 1861, the Military Telegraph Service was a contract agency of the Quartermaster Department rather than the Signal Corps. It served under the direct control of either the Superintendent of the Military Telegraph Service or Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, and functioned separate from the military. Civilian telegraphers or construction workers by profession composed its membership.

Not bound by military discipline or control from military officers, members of the Telegraph Service sometimes drew the ire of field commanders. In one case, Gen. Ulysses S. Grant tried to enforce discipline, only to be officially reprimanded and reminded that the Service was not under his command.

Some telegraph workers were rowdy and prone to drinking. Though the uncivil behavior undoubtedly rankled officers, the Service workers typically labored under dangerous circumstances. More than three hundred telegraphers and support workers became war casualties from disease, death in battle or capture. One historian calculated that the Service had a casualty rate of 1 in 12, compared to 1 in 5 for all Civil War soldiers.

Francis Trevelyan Miller, in his epic series Photographic History of the Civil War, described the telegraphers as, “men of rare skill, unswerving integrity, and unfailing loyalty.”

Working conditions varied greatly. In the field they worked in tents, crude shelters or bombproofs as before Petersburg. On the other hand, the men, and at least one lady, that worked in more urban environments enjoyed greater comforts. The telegraph benches in Washington had marble tops, which were once decorated with ink smears by Tad Lincoln. The supervisor who caught the boy escorted him out of the office by the scruff of his neck and the seat of his pants. The supervisor encountered the boy’s laughing father, who took him in hand.

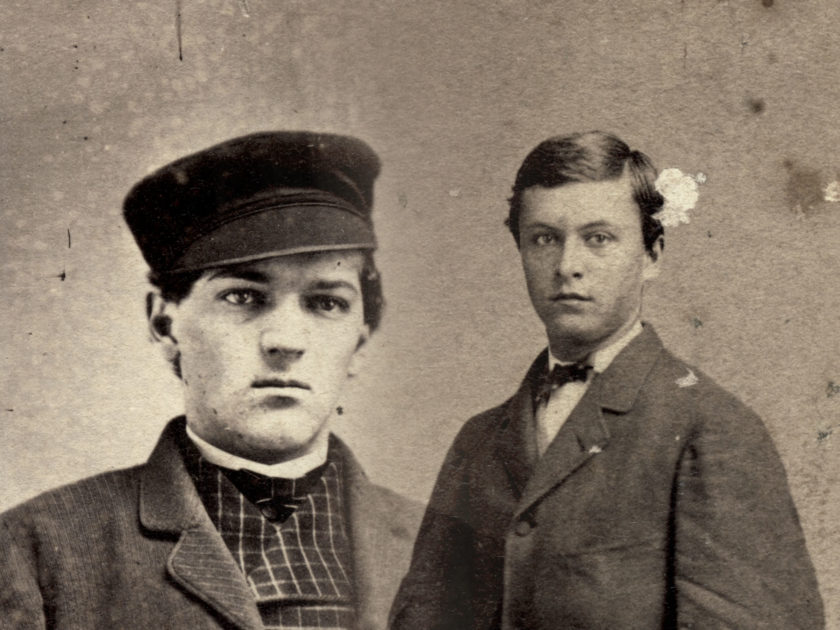

Those that worked in the field or in enemy territory were often considered, despite their civilian status, as fair game by the enemy. Some died in action, while others were murdered by guerillas. The Service had no prescribed uniforms or badges. A few workers wore bits and pieces of military uniforms in hopes of protection. But by in large, most reported for duty in civilian clothing.

A uniform was authorized in June 1864 in one particularly dangerous area—the valleys of the Cumberland and the Tennessee. It featured a light blue sack coat and trousers with a chasseur style blue forage cap. Unfortunately this author knows of no extant photographs of it and can provide only members of the Service in mufti.

MI Senior Editor Michael J. McAfee is a curator at the West Point Museum at the United States Military Academy, and author of numerous books. He has curated major museum exhibitions, and has contributed images and authoritative knowledge to other volumes and projects.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.