So Close, So Far

The roughly 400-strong 11th Mississippi Infantry participated in Pickett’s Charge. The assault cost the regiment about half its number.

Among the survivors was Pvt. John F. Brown, opposite, a native of Ohio. A 16-year-old student at the University of Mississippi in Oxford when the war began, he and a number of his college buddies joined the Lamar Rifles. It became Company G of the 11th and fought in major engagements with the Army of Northern Virginia, including the Battle of Antietam, where it lost the regimental colors.

Following Pickett’s Charge, Brown and the regiment retreated with the Confederate army and made its way home. At Falling Waters, a bucolic spot along the Potomac River about 50 miles southwest of Gettysburg, Union forces attacked. Wounded, Brown fell into enemy hands, but was exchanged and furloughed the same day. The exact nature of his wound was not reported, but it was serious enough to end with his discharge from the army in 1864.

Brown spent the rest of his life in Oxford, where he married twice, and had two children. In 1906, he participated in dedication ceremonies for Oxford’s Confederate monument. He died at age 72 in 1918.

Trouble at Manassas Gap

Three weeks after the Battle of Gettysburg, fighting continued between the blue and gray armies. On July 23, along Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains at Manassas Gap, a column of federals hit the Confederates. In the fighting that ensued, 440 men became casualties, including 2nd Lt. John Lewis Ells, Jr., of the 3rd Georgia Infantry.

The Yankee who shot Ells in the hip could not have known that he had taken out an officer who had once lived in the North. For about a decade, beginning in the late 1840s, he had resided in Troy, N.Y., the home of his grandparents and other relatives.

Ells returned to the South about 1858, and joined the 3rd in 1861. He participated in numerous engagements with the Army of Northern Virginia, including Antietam, where he suffered a minor wound. His injury at Manassas Gap ended his service. The bullet lodged near his right hip joint, and surgeons could not extract it. He left his regiment in December 1864, unable to walk without the assistance of a cane or crutch.

After the war, Ells worked in Augusta and Atlanta, Ga., as a newspaperman. He moved with his family to Baltimore, Md., where he died in 1889 at about age 60.

Hit Near the Stone Wall

Growing up in a Quaker household in Northern Virginia, Kirkbride Taylor respected peaceful principles. But after war divided the country, he set aside his medical studies and joined the 8th Virginia Infantry as a first sergeant. The regiment fought in many early Virginia actions, including the 1862 Battle of Glendale, where Taylor sustained a minor wound.

The following year at Gettysburg, Taylor was on the skirmish line during Pickett’s Charge. As he approached the stone wall near the Copse of Trees, a minié bullet struck him on the side of the head, but did not penetrate the skin. He fell back and safely returned to the Confederate lines.

Taylor later became an officer. In June 1864, during the fighting around Petersburg, he suffered his third wound of the war when a gunshot hit him in the right chest. This injury ended his combat career.

After the, war he returned to Virginia, resumed his studies, and became a physician. He married and had two children. Upon his death at age 73 in 1913, the mourners who paid their respects took note of an unusual indentation on his head—the result of his Gettysburg injury.

Deadly Seventh Day

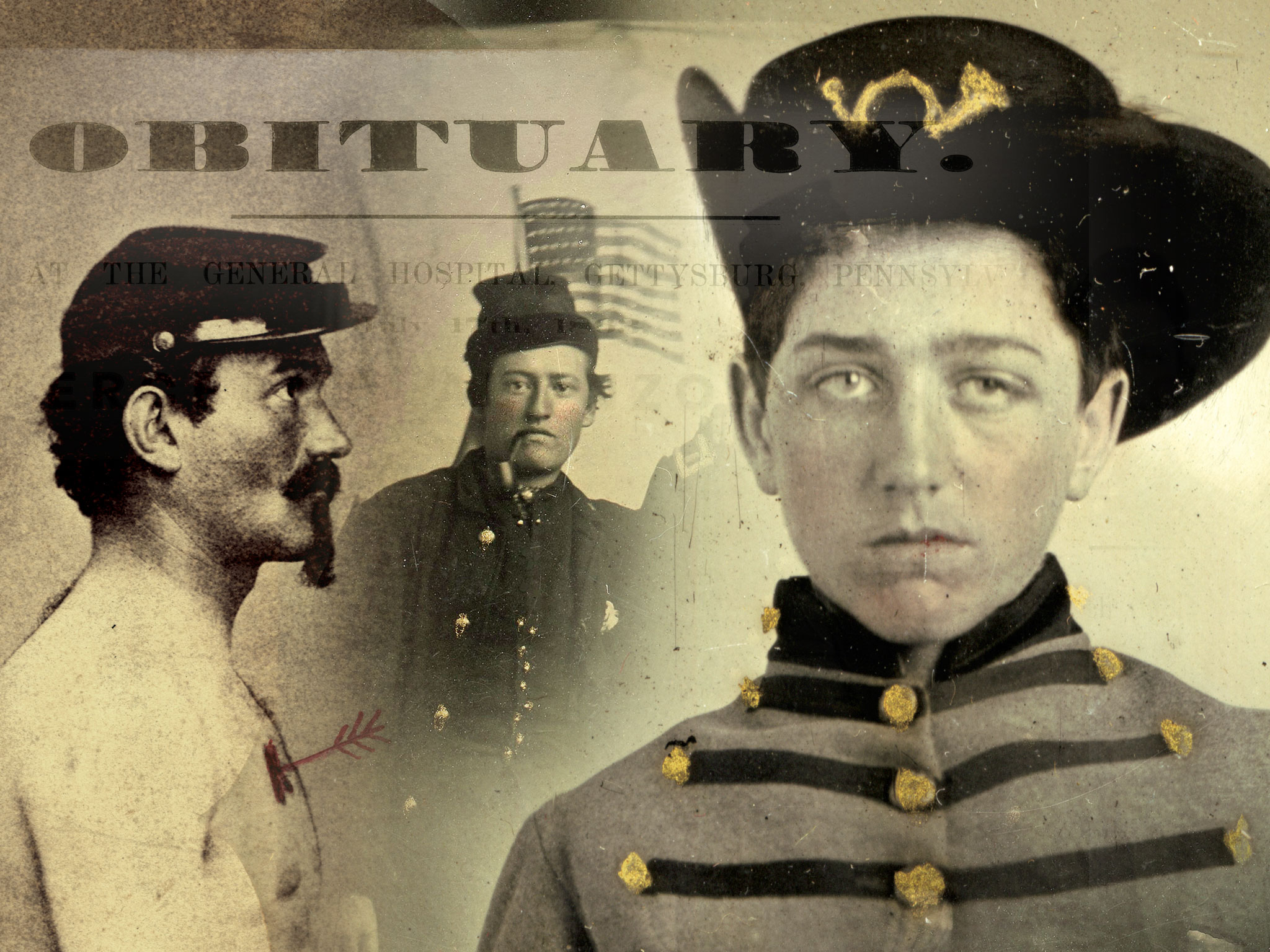

The Union pursuit of retreating Confederate forces following Gettysburg resulted in clashes large and small. One engagement, at Funkstown, outside Hagerstown, Md., began on July 10 as a cavalry action that pitted blue and gray divisions against each other. Both sides eventually called up infantry reinforcements. When the fighting ended, close to 500 men became casualties, including Augustine Leftwich, Jr., of Shoemaker’s Battery, Virginia Horse Artillery. He is pictured here in two wartime portraits.

Leftwich suffered wounds in the lungs and a shoulder. Carried to the College of St. James, a nearby preparatory school, he received treatment at the institution’s hospital. A friend called in from New York City made sure all his needs were met. Despite his efforts, and the assistance of local women from Hagerstown, Leftwich succumbed to his injuries on July 29. A prominent Episcopal minister, Rev. John Barret Kerfoot, tended to his spiritual needs at the end. Leftwich’s remains were placed in a fine walnut coffin, and buried in St. John’s Episcopal Church Cemetery in Hagerstown.

The clergyman wrote a letter to his family in Lynchburg, Va., informing them of the tragedy.

Hospitalized Two Years Later

The injury that prompted Pvt. Ludwig Kohn’s admission to a military hospital in Washington, D.C., on Aug. 15, 1865, had actually occurred two years earlier at Gettysburg. During the first day of the battle, Kohn and his comrades in the 26th Wisconsin Infantry marched through the streets of Gettysburg and took up a position north of town. The 26th and its brigade soon came under heavy Confederate attack. It held its ground until a brutal flank attack drove them back.

At some point, a bullet struck Kohn in the right side of the chest, fracturing a rib and passing through his body before exiting his back below the shoulder blade. Kohn told a doctor, “The wound soon after the injury became gangrenous with considerable sloughing of soft parts; spit blood at times, and that the wound was so painful as to deprive him of his night’s rest; could not lie on his back, but was obliged to sit up day and night.”

By March 1864, it had become clear that his combat days were over, and he transferred to the Veteran Reserve Corps. Discharged in June 1864, he rejoined the army in March 1865 as a private in the 214th Pennsylvania Infantry. Medical personnel who examined him upon his hospital visit in August 1865 found that the wound had mostly healed, with the exception of a small fistulous opening. He deserted the regiment on Jan. 14, 1866—the last time his name appears on a government record.

Record Rounds in Support of Pickett’s Boys

The Confederate gunners that manned Capt. William W. Parker’s Battery fired a record number of rounds in one day—1,142—in support of Pickett’s Charge. They finally withdrew in the evening, only to learn from disappointed infantrymen that the assault had failed.

Among the 90 artillerymen who participated in the barrage was Pvt. George Washington Hancock, a resident of Manchester, Va., part of the city of Richmond. His time in gray landed him on casualty lists twice. At Gettysburg, he was wounded on July 3, though the nature of his injury went unreported. In the closing days of the war, on April 6, 1865, he fell into enemy hands during the Battle of Sailor’s Creek. His captors took him to Point Lookout, Md., where he signed the oath of allegiance to the federal government two months later.

Hancock returned home and lived quietly until his death in King William County in 1917. His wife, Alice, and two daughters survived him.

Second Wounding, First Capture

The first two days of the battle proved pivotal for Pvt. Joseph W. Thayer and his comrades in the 12th Massachusetts Infantry. On the first day, the Bay Staters did their part to slow the Confederate onslaught that inflicted so much damage to the Union army. On the second day, they supported various positions along the lines. At some point during the fighting, Thayer suffered a thigh wound and fell into enemy hands.

Thayer had a hard time getting into the army. His first attempt to enlist, at age 16 in April 1861, failed after his father found out. Weeks later, when the 12th formed, Thayer ran away from home, and, this time, successfully enlisted. He suffered his first wound, a minor injury, at the Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862. At Gettysburg six months later, he was left behind when his captors withdrew after the battle. Thayer recuperated in hospitals at Fort Schuyler, N.Y., and Lovell General Hospital in Portsmouth Grove, R.I., where he sat for this photograph. In early 1864, he joined the Veteran Reserve Corps, and ended his service later in the year.

Thayer returned home after the war and worked for a photographer and as a customs inspector. He died in 1905.

“He Had Been Where the Angels Were”

A memorial card recalls the life and military service of 1st Sgt. Alonzo J. Babcock of the 2nd Massachusetts Infantry. A weaver at his enlistment, he suffered a wound during the Culp’s Hill assault best remembered by the words of the regiment’s commander, Lt. Col. Charles R. Mudge, who responded to the order to attack, “Well it is murder, but it’s the order.” Babcock, part of the color guard that day, was one of about 135 casualties in the regiment. His widowed wife, Abby, whom he had married eight years earlier, survived him.

The individual who signed the obituary, and presumably its author, is Rev. James P. Ludlow (1833-1898). A native of Charleston, S.C., he took a break from his studies at the Rochester Theological Seminary to minister to soldiers under the auspices of the influential U.S. Christian Commission. He was ordained a Baptist minister in 1864 and went on to a long career in service to his faith.

Four Fighting Orange Blossoms

The Confederate attack on Devil’s Den and Houck’s Ridge during the afternoon of July 2 decimated the 124th New York Infantry. Just two months earlier at the Battle of Chancellorsville, the regiment had been branded the “Orange Blossoms” by its colorful colonel, Augustus van Horne Ellis. But now, Ellis lay dead, after a bullet in the brain toppled him from the saddle during a countercharge against the oncoming rebels at Houck’s Ridge.

His body, and that of the major of the 124th, was placed under the guard of 2nd Lt. and adjutant Henry Powell Ramsdell, pictured here on the far left with lieutenants William Brownson, Henry Travis and James Finnegan, who suffered a wound at Gettysburg.

Ramsdell transported the remains home to New York. It was a harrowing journey as martial law and military red tape prevailed in the wake of the Confederate invasion. Still, he, along with nine men and the colonel’s servant, Sam, carried the bodies on stretchers about three miles, and then commandeered a wagon and horses. They continued to Baltimore, where they obtained metallic caskets, and finally on to New York by train. Grieving families received the bodies. With its mission accomplished, the detail returned to the regiment.

Ramsdell left the 124th with his first lieutenant’s bars and a disability discharge before the end of the year. He returned home, and worked as a paper manufacturer. He died in 1934 at age 89.

Grim Distinction in His Regiment

According to the regimental history of the 148th Pennsylvania Infantry, Pvt. George Osman of Company C was an unusual character. “Always in a good humor, no matter how arduous the duty, it was willingly and cheerfully performed.” The historian added, “I don’t think he ever uttered one word of complaint.”

During the second day’s fight, Osman and his comrades moved into position near Cemetery Ridge. Confederate cannon soon found them, and prompted the Pennsylvanians to change position. A number of the men, exhausted from the march into Gettysburg, took advantage of the opportunity to catch a few winks despite the occasional artillery fire. “George Osman, who was no doubt in a sleep, was hit by a spent shell which struck him on the cartridge box. It was a terrible shock from which he did not recover,” recalled his nephew, Lemuel, who served with Osman in Company C.

Osman was the first soldier in the 148th to die at Gettysburg. He was 25. His remains were interred in Gettysburg National Cemetery.

Casualty at Kuhn’s Brickyard

During fighting at Kuhn’s brickyard on the first day of the battle, Pvt. Edward D. Coe of the 154th New York Infantry was wounded in the left arm near the shoulder. The ball chipped his humerus and damaged muscles and ligaments. He fell into enemy hands, and reportedly was kept at a stone house where high-ranking officers dined.

Coe, a 30-year-old farmer and lifelong resident of French Creek in Chautauqua County, N.Y., had enlisted in August 1862. He mustered in the following month as a private in Company F of the 154th. Less than a year later at Gettysburg, Coe was left behind when the Confederates retreated. He was sent to Summit House Hospital in Philadelphia and stayed there until July 1864, when he transferred to the Veteran Reserve Corps. He discharged in July 1865 at Camp Coburn in Augusta, Maine. Coe married Abigail Beach in 1868; they had one son, Judson. Coe died in 1912.

A Fallen Bucktail

Pvt. Isaac Mall and his fellow Bucktails in the 149th Pennsylvania Infantry were called to defend their country and their home state on July 1. The Keystone Staters, along with the other two regiments in their brigade, deployed south of the Chambersburg Pike beside McPherson Ridge. According to a regimental historian, “It maintained its position with great heroism throughout the first day until the whole line retreated through the town.”

The “whole line” was a mere remnant of the regiment—of the 450 men who began the day’s fighting, 336 became casualties, or about three-quarters of the men. Pvt. Mall was among the fallen. He was about 22 years old. His remains lie in the Gettysburg National Cemetery.

Wounded in Defense of Blocher’s Knoll

Confederate forces thrashed the 68th New York Infantry and the rest of the Eleventh Corps on the first day of the battle. The regiment, composed largely of German immigrants, included 1st Lt. and adjutant Carl Riese. At some point during the action, probably during the attack on Blocher’s Knoll, he suffered a wound that took him out of action.

The two officers flanking him fared better. Capt. Edward Kaysing, on the right, had left the regiment with a discharge six months earlier. 1st Lt. Theodore Feldstein emerged from the fighting uninjured.

Riese survived his injury and served through the war. He mustered out of the army at Fort Pulaski, Ga., in November 1865. His post-war whereabouts are not known.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.