By Fred D. Taylor

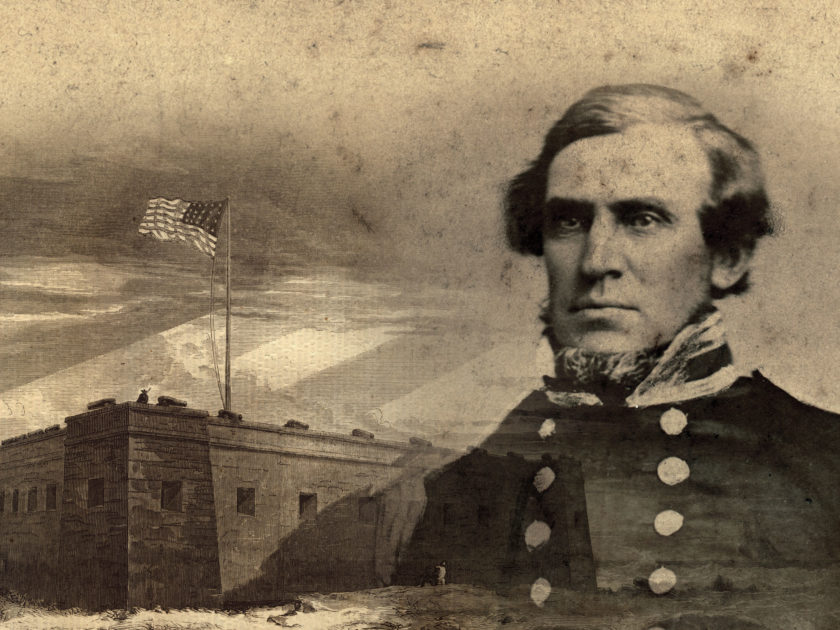

A man of untiring zeal and firmness of character, Lieutenant Otway Henry Berryman was no stranger to the expectations of an officer. In fact, his 32-year career in the United States Navy had been battle-tested many times before the outbreak of hostilities between the States. This time was different, however. Never had his decision-making been as important. Now, his foes were former comrades, friends, and Southern kin who carried the banners of secession. For Berryman, the decision he would make next and its result would affect his family for years to come.

Berryman’s tragic tale began in Virginia. Born in Caroline County in 1812, he spent his early youth traveling alongside his successful merchant father. Ultimately, the family settled in Washington, D.C. While residing in the nation’s capital, Berryman received an appointment as Midshipman in the U.S. Navy in 1829 at the tender age of 16.

Berryman gained immediate naval experience, serving on board the sloop Ontario in the Mediterranean Squadron, performing coastal survey duty, and working at the Washington Navy Yard, all of which duties earned him a promotion to Passed Midshipman by 1835.

At the age of 29 in 1841, Otway Berryman was commissioned as a lieutenant and ordered to duty with the ship of the line Delaware, under the watchful eye of Cmdr. David G. Farragut. For the next three years, the Delaware served in the South Atlantic Squadron, patrolling the coasts of Brazil, Uruguay, and Argentina.

Upon commencement of the Mexican-American War, Berryman joined the brig Truxton. Ordered to the Gulf of Mexico, the ship was intended to support the blockade of Mexican ports. In August 1846, however, the Truxton ran aground near Tuxpan. Attempts to free the brig were unsuccessful. Fearing destruction, Berryman was dispatched on a recently captured Mexican vessel to seek assistance. Although days later the Truxton surrendered to Mexican authorities at Tuxpan, Berryman succeeded in his enterprise. He and his crew captured another Mexican schooner while en route, and presented both prize ships to Cmdr. David E. Conner at Anton Lizardo, Mexico.

In recognition for his efforts, Berryman received command of his own vessel, the schooner Onkahye. For the next year-and-a-half, the vessel patrolled Caribbean waters and the South American coast, seeking out pirates and slave ships. The Onkahye’s efforts proved highly successful, but disaster struck in the summer of 1848 when the ship was damaged by reefs and shipwrecked near the Turks and Caicos Islands. Eventually, the Onkahye was abandoned. A Navy court of inquiry was convened, but assigned no blame to Berryman or his crew for the ship’s loss.

Returning to the States, Berryman was recruited by noted oceanographer and navy officer Matthew Fontaine Maury to test new routes and study the winds and sea currents. This expedition involved several years of travel between North America and Europe, performing deep sea soundings in the Atlantic Ocean and examining shipping routes. In 1856, he worked with the Oceanic Telegraph Company to survey the route between St. John’s, Newfoundland, and Valencia Bay, on the southwest coast of Ireland, to determine the feasibility of laying a sub-marine telegraph line.

Following these scientific explorations, Berryman resumed his service with the receiving ship Pennsylvania at the Gosport Navy Yard in Portsmouth, Va. He subsequently commanded the Falmouth, a stationary store-ship that served U.S. interests in Panama.

With the Presidential election of 1860 on the horizon, naval interests on the domestic front took priority. Berryman was ordered home, returning just weeks before the election of Abraham Lincoln. Soon thereafter he was sent to Florida to take command of the gunboat Wyandotte, where it was hoped his patience and Southern leanings might calm an otherwise tense situation. He replaced the zealous Lt. Fabius Maximus Stanley, who successfully commanded the Wyandotte just a month before in Key West, protecting Fort Taylor from capture by secessionists. Due to his actions, outgoing President James Buchanan sent Stanley packing to a less controversial location, at the Mare Island Navy Yard in California.

Upon arrival at Pensacola, Lt. Berryman found the Wyandotte under repair in dry dock—and Florida on the eve of secession. At this critical time, Berryman received orders to depart with his ship to protect U.S. interests and see to the provision of Fort Pickens in Pensacola Bay. Two days later, threatened by a significant armed force at their gate, the Navy surrendered the Pensacola Navy Yard. Instructed by Southern officials to abandon the Wyandotte prior to the surrender, Berryman refused. He continued to use his ship as a convoy between the Navy Yard and Fort Pickens, recovering food supplies, arms, and transporting sailors and marines.

Berryman did not arrive at his decision without difficulty. He had also been ordered to avoid firing a gun unless it might be necessary in defense of his ship. Fortunately, with the surrender of the Navy Yard on January 12, the federals and the Confederates reached a gentlemen’s agreement. The Southern military would take no further action as long as the federal government refrained from reinforcing Fort Pickens. In exchange, Berryman was permitted to ferry mail, provisions and fresh water between Fort Pickens and the mainland with the Wyandotte.

This was the only good news that Berryman received at the time. By February, all of his subordinate officers—save one Engineer—had resigned to join the Southern ranks. Similarly, the agreement to allow transport back to the mainland was terminated within a month, as the Confederates laid siege to Fort Pickens.

While Berryman made the most of his situation, balancing his loyalty to the U.S. while keeping the anxious Southern secessionists at bay, he was clearly torn. To his credit, fellow U.S. officers noted Berryman could not be “induced to swerve from the path of honor and duty” and “in the teeth of insurrectionists, with an overwhelming force around him, not only advocated, but stood up for and maintained his country’s flag and honor.”

Still, Berryman struggled with his divided loyalties. When ultimately questioned about his Virginia lineage, Lieutenant Berryman conceded that, “My orders from the proper authorities of a government I have loved and served as faithfully as I could, I still respect, and when that government shall be dissolved by the decision of my great and noble state [Virginia], I hope to prove myself worthy of holding a commission even under a Southern Confederacy.”

Such sentiment did not make his current task any easier. Berryman’s native Virginia had actually elected a pro-Union Convention, and within days that Convention would vote overwhelmingly against secession. However, the debate over secession raged in Virginia, and the potential for an attack increased upon Fort Pickens and the Wyandotte.

The stress of the situation took a toll on Berryman. A short illness resulted in his death due to “brain fever” on April 3, 1861. His attending Surgeon recalled, “For weeks previously Captain Berryman had been in a great degree of political excitement and watchfulness to prevent the capture of his vessel. He had slept but little, and none for the three days previous to his death. He was literally worn out by his constant activity and sense of responsibility.”

Confederate officials were notified hours later. The news shocked Capt. Duncan Ingraham, commander at Pensacola Navy Yard. He recalled that, “Only Saturday he was laughing and talking, and he looked in perfect health. Truly ‘in the midst of life we are in death.’” Ingraham issued orders allowing the U.S. to take any and all measures necessary for the funeral and burial of Lt. Berryman.

The next day, on April 4, 1861, at 3 p.m., the remains of Berryman were conveyed from the Wyandotte to the wharf at the Navy Yard under a flag of truce. The procession featured 30 U.S. Marines and a U.S. military band accompanied the hearse and a flag-draped coffin with Berryman’s cap and sword on top of it.

“They forgot, for the hour, the thoughts of carnage, and met like friends, over the grave of a brother officer.”

The pallbearers included both federal and Confederate officers. Among those present were Col. Henry D. Clayton, C.S. Army; Dr. H.S. Garnett, U.S. Navy; and Capt. Thomas W. Brent, C.S. Navy. Additionally, approximately 100 sailors from the U.S. ships Brooklyn, St. Louis, Sabine, and Wyandotte followed the coffin, as well as Naval and Marine officers, and Capt. A.J. Slemmer, commander of Fort Pickens. On the Southern side, Gen. Braxton Bragg issued a general order that all Confederate officers were to attend the funeral. The funeral procession included such officers and local citizens, as well as Ingraham and Bragg.

The remarkable event, briefly bringing together North and South in the midst of war, caught the attention of newspapers across the nation. One report noted, “Death sometimes brings the human heart to thoughts quite foreign to the daily routine of men’s minds… While preparing to wage war against each other, these brave men were suddenly called to perform the last offices of affection towards one whose duties here have been brought to a close. They forgot, for the hour, the thoughts of carnage, and met like friends, over the grave of a brother officer.”

Berryman received last rites from the Rev. Dr. Scott, and was laid to rest in the vault of St. John’s Episcopal Church. At the conclusion of the war, his remains were transferred to Barrancas National Cemetery in Pensacola, where he rests today beneath a simple granite marker.

Steadfast in his loyalty to his country to his last breath, Berryman remained worthy of the pride of his family and state.

References: Government Printing Office, Report No. 121, Reports of Committees of the House of Representatives made during the Second Session of the Thirty-Seventh Congress; French, Biographical Sketches, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Va.; U.S. Navy Register, 1834 and 1837; Newbern Spectator (Newbern, N.C.), Oct. 30, 1841; Abbot, Navy History of the United States, Vol. 2; Tucker, Spencer, editor, et al., Encyclopedia of the Mexican-American War, Vol. 1; The Executive Documents, printed by Order of the Senate of the United States, Second Session, Thirty-Fifth Congress, 1858-’59, and Special Session of the Senate of 1859; Message from the President of the United States to the Two Houses of Congress, Part III, 1853; Richmond Enquirer, May 20, 1853; The Sun (Baltimore, Md.), June 28, 1856, and Feb. 4, 1861; New York Times, Nov. 3, 1860; Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion; New York Daily Herald, Feb. 5, 1861; Vicksburg Whig, April 17, 1861; Wilmington Daily Herald, April 17, 1861.

Fred D. Taylor is a son of Virginia, an attorney, collector, and a life-long student of history. Fred can be reached for questions or comments about his article via e-mail at fred.taylor.va@gmail.com.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.