By Ronald S. Coddington with Warren “H” Shindle and Glenn Ethridge Hilburn

The phone call that came in to Glenn Hilburn’s antique shop in Frederick, Md., on a spring day in 2016 was intriguing. A family was selling off the remains of an estate—pottery, bottles, furniture and pictures. A longtime bottle collector and veteran antiques dealer, Hilburn and a buddy hopped into his truck and drove over to check it out.

Before long, they found themselves shuffling through the house, picking through the various odds and ends. The owner had sold off her estate in bits and pieces over the years. Now, she was deceased, and surviving family members wanted to dispose of whatever remained. Hilburn purchased everything. The bill of sale reads “Contents of house.”

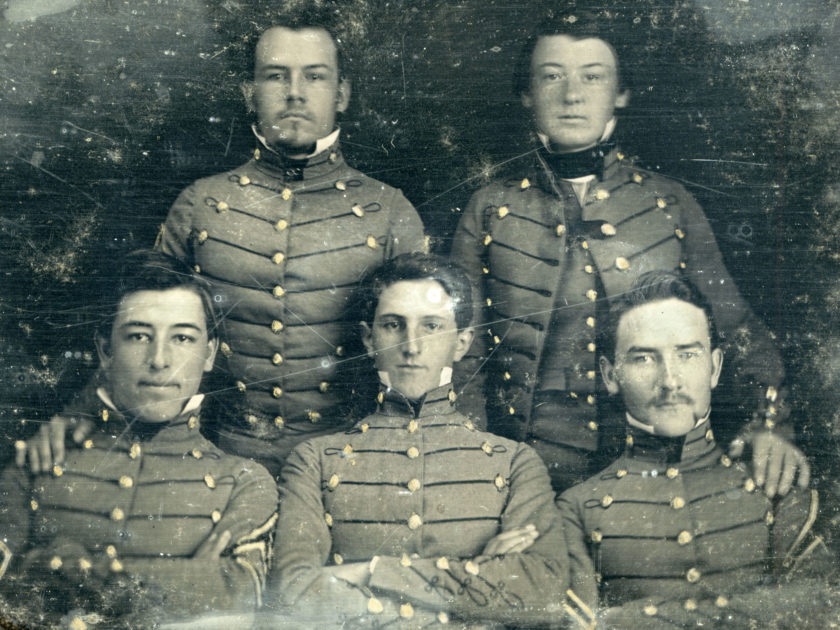

As Hilburn rummaged through one box of old family papers, he found a photographic case at the bottom. Opening it, he found five cadets staring back at him.

“I knew what it was as soon as I saw it,” Hilburn recalled. “As soon as I saw the uniforms, I knew it was one of the big military schools.” One of the cadets, Hilburn thought, resembled famed future Civil War cavalry general and Indian fighter, George Armstrong Custer.

Back at the shop, and later at his house, Hilburn sifted through the box searching for clues about the young men in the quarter-plate daguerreotype that had captured his attention. He quickly determined that the papers related to the Winston family. Their descendants had once owned the house. Hilburn found meticulously labeled genealogical charts that documented the lineage of the Winstons, and a number of old photographs that pictured family members. He noticed that several post-Civil War portraits of one man, Lucien Dade Winston, closely matched the likeness of the cadet standing on the right of the daguerreotype.

Winston, as it turns out, was a cadet at the Virginia Military Institute. The youngest of seven children born over two decades to a wealthy Virginia farmer and his wife, he had grown up outside Culpeper, Va., along the Rapidan River near Raccoon Ford. In 1853, at about age 17, he entered VMI for his freshman year.

He was not the first Winston to attend VMI. Older brother Isaac, Class of 1848, went on to serve as an Indian agent, marshal and President James Buchanan’s Consul to Jamaica from 1859-1861. He sat out the Civil War however, and became a teacher.

Winston probably posed for this portrait in the winter of 1853-1854, during his first, and what would be his only, year at the Institute. Noted VMI collector Warren “H” Shindle observes that all the cadets are dressed in wool trousers worn during the cold months of the year. (In warmer weather, cotton duck pants replaced the wool.) The gray coatee jackets, common in VMI portraits made after 1850, are consistent with Winston’s enrollment. If the cadets had been photographed prior to 1850, Shindle explains, they would have likely sported elegant navy blue “furlough” coats fastened with 11 high-dome buttons embossed with a unique VMI Cadet Virginia seal.

Winston’s jacket is the only one unbuttoned, revealing his vest and, what Shindle believes, a black mourning ribbon affixed to the second button below his collar. Another button, presumably attached to the ribbon, has been inserted into the buttonhole of his coatee. The photographer gilded this and the other coat buttons, a common practice in military daguerreotypes and other hard-plate images. If a mourning ribbon, it may honor his recently deceased parents. His mother, Mary Howson Wallace Winston, had died on Nov. 9, 1853. She barely outlived his father and her husband, William Alexander Winston, who had passed on New Years Day 1853.

Though the photographer is not identified, Shindle suggests that he is Samuel G. Pettigrew (1828-1868). The Virginia-born daguerreotypist was one of many photographers who operated studios in Lexington, home of VMI, during the 1840s and 1850s. He did a brisk business in portraits, including an 1857 likeness of bewhiskered instructor Thomas J. Jackson before he acquired military fame as “Stonewall.”

The Pettigrew theory is founded on the crossed arms of the seated cadets. Shindle observes that surviving images of cadets who struck this pose occurs from about 1850 to 1860. This timeframe coincides with the years that Pettigrew published newspaper advertisements to promote his business.

Shindle also explains, “In general, cadets posed together are classmates and assumed to be barracks roommates.” In this case, two classes appear to be represented. Three cadets from the Second Class, or the Class of 1855, wear sergeant’s chevrons on their coatee sleeves. The cadet seated on the left is a quartermaster sergeant. These cadets appear older, as evidenced by wisps of facial hair on two of them. To date, their identities remain a mystery.

“Winston came away from his military experience inspired by a battlefield dream to establish a village for peaceful, God-fearing folk.”

Winston and the young man seated in the center belonged to the Freshman Class, or as upperclassmen called them, “Rats,” a term that came into use during the 1850s to describe new cadets. Tradition holds that the moniker had its origins a decade earlier. In the 1840s, cadets and students from nearby Washington College (now Washington and Lee University) drilled together. The students, according to legend, mocked the cadets as “rats” because their gray uniforms reminded them of the rodent.

This term continues today, as cadet elders remind contemporary Rats of their status. According to VMI, “Rats are required to walk at attention in barracks along a prescribed line (hence the name Rat Line), obey stringent regulations, strain (assume an exaggerated position of attention), or drop for pushups if found deficient in any way by an upper-class cadet while in barracks,” and other particulars.

One can reasonably conclude that these behaviors grew out of the campus culture of the 1850s. If so, and assuming the five cadets in the daguerreotype are, as Shindle suggests, barracks roommates, this portrait tells the story of cadet hierarchy.

So who is the Rat seated in the center? The cadet that reminded Hilburn of Custer might be related to Winston. Shindle points out that, “Occasionally, family relatives also attending VMI are included in these group poses.” A study of Winston’s family tree surfaces the surnames Boddie (or Bodie), Dade and Slaughter. One cadet who attended VMI during Winston’s brief stay was Philip Peyton Slaughter. He lived in Madison Hill, Va., about 15 miles from Winston’s home in Raccoon Ford. Slaughter graduated in the Class of 1857 and became an instructor at his alma mater. During the Civil War, he served first as a second lieutenant in the 13th Virginia Infantry and later as lieutenant colonel of the 56th Virginia Infantry. A photo of Slaughter reproduced in the regimental history bears a resemblance to the cadet in Hilburn’s daguerreotype.

Slaughter’s commander, Col. William D. Stuart, had graduated from VMI in 1850. On July 3, 1863, at the Battle of Gettysburg, the highly regarded colonel suffered a mortal wound during Pickett’s Charge. Slaughter, hobbled by a thigh wound a year earlier in the fighting at Gaines’ Mill, briefly commanded the regiment until it and other Confederate forces retired from the field. Slaughter survived Gettysburg and ended the war as a colonel. He lived until 1893.

What became of Winston? After the death of his parents in 1853, “Luce” inherited part of a vast family estate—1,200 acres of land and a personal fortune of $23,000 (about $700,000 today) that included 50 slaves. His inheritance stayed in a trust until age 21. It may have been this sudden change in his fortunes that prompted his early departure from VMI.

Whatever the reason, when war divided the country in 1861, Winston, like Slaughter, joined the 13th Virginia Infantry. Unlike Slaughter, an officer in Company A, he had enrolled as a private in the Culpeper Minutemen, which became Company B of the regiment. He and his comrades were present at the First Battle of Manassas in July 1861, but did not engage Union forces. After his 6-month term of enlistment ended in January 1862, Winston joined Purcell’s Battery, an artillery unit named for John Purcell, a wealthy Richmond merchant who financed equipment for the gunners. The battery was part of the Army of Northern Virginia for the majority of its service. Its best-known member, William R.J. Pegram, became one of the army’s most distinguished artillery officers. Pegram suffered a mortal wound at the Battle of Five Forks on April 1, 1865.

Winston’s exact battle record is not known. An examination of his military service records indicates his absence on detached duty for much of his enlistment, including a stint in the commissary department of the Third Corps artillery that required much of his time from the spring of 1864 through the war’s end.

According to descendants, Winston came away from his military experience inspired by a battlefield dream to establish a village for peaceful, God-fearing folk. The dream was about all he had. The war had cost him his home, Vinegar Hill, which he lost due to the inability to pay taxes. Land-poor and out of cash, his dream lingered until the late 1870s. By this time, he had relocated to Kentucky, where, in 1878, he married Elizabeth McNeill Boddie, the daughter of a wealthy Mississippi plantation and Kentucky farm family. He invested some money she gave him, along with some of his own, in shrewd real estate deals.

He eventually realized his dream. In 1887, the fledgling community of Winston, Va., secured a post office. Upon his death in 1914 at age 78, Winston was buried on the grounds of a stone chapel he had built a few years earlier. The church cemetery grew as other members of the family passed from the scene. Meanwhile, the village of Winston slid into decline, and today is mostly a rural ruin.

The chapel and this newly discovered daguerreotype that marks Winston’s brief connection to VMI provide precious relics of a Virginian who had a dream inspired by war. One wonders about the undiscovered stories of the other cadets yet to be told.

References: Emails with Col. Keith E. Gibson, Director of the VMI Museum System, and two staff members of the Special Collections department of Washington and Lee University Library: Seth McCormick-Goodhart and Byron Faidley; Virginia Military Institute Historical Rosters Database; Virginia Military Institute, “The Ratline;” Free-Lance Star (Fredericksburg, Va.), July 24, 1999; Lucien D. Winston military service record, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

MAJ Warren “H” Shindle, Corps of Engineers, USAR (Ret) graduated from Virginia Military Institute in 1985 with a Mechanical Engineering Degree. Shindle is also a Professional Engineer and a Licensed Auctioneer in Virginia. He has been collecting and researching VMI images for over thirty years and will publish a forthcoming “VMI Faces” book. Please consider forwarding your VMI Cadets for inclusion into this volume.

Born in Los Angeles, Calif., Glenn Ethridge Hilburn served four years in the navy and graduated from San Jose State College in 1963. He earned his masters degree at George Washington University. A retired teacher, he has been married for 45 years and has three children and three grandchildren. An antiques dealer and collector since 1968, he lives in Frederick, Md.

Ronald S. Coddington is Editor and Publisher of MI.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.