By Charles T. Joyce

Fields thick with golden wheat and oats blanketed the southeastern Pennsylvania countryside surrounding the hamlet of Fayetteville during the early summer of 1863. On June 28, however, an encampment of Confederate invaders disrupted the bucolic scene.

Soldiers of the 26th North Carolina Infantry gathered together on this Sabbath morning to hear their chaplain preach. He quoted from the Book of Jeremiah’s chapter 8, verse 20: “The harvest is finished, the summer is ended, and we are not saved.”

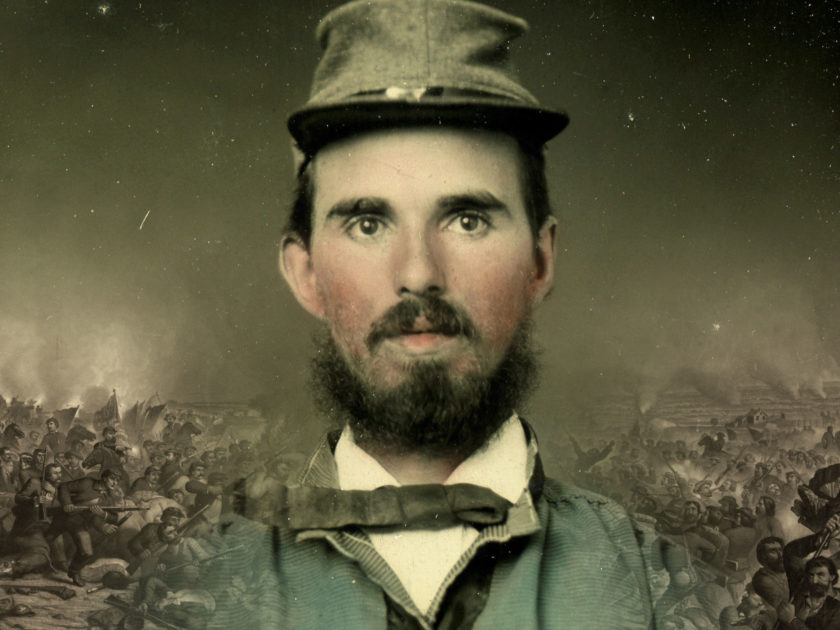

The words would prove all too true in the days to come. One young North Carolina officer who would experience the trials and tribulations of battle firsthand was John R. Emerson. A 24-year-old farmer from Chatham County, N.C., Emerson hailed from a line of rebellious and militant men. His great-grandfather, James Emerson, had fought in the War of the Regulation, an agrarian protest against British colonial dictates that had occurred in the Carolina colonies prior to the American Revolution. In 1771, he had been captured at the Battle of Alamance and nearly hanged, drawn and quartered for treason against the Crown.

In May 1861, Emerson joined a Chatham County militia company, the “Independent Guards,” as a second corporal. His timing was noteworthy. Only three months earlier, he had married Martha Frances “Pat” Yarbro, a woman about four years his senior. For this reason, perhaps, he affectionately addressed her in letters as “my old woman.” In September, Emerson made out his will and left all he owned to Pat, unless their union would someday produce an heir. He revealed his testamentary plans to her in a letter the following month. In it, he playfully reminded her to tell her female friends “not to forget our brave boys that have given up their cheerful homes for their liberties.”

The Guards soon joined the 26th as Company E. The colonel of the regiment was former U.S. Rep. Zebulon Vance. Interested more in politics than warfare, Vance left the training of the citizen soldiers to his second-in-command, Lt. Col. Henry King Burgwyn, Jr., a 19-year-old graduate of the Virginia Military Institute. Burgwyn advanced to colonel in the summer of 1862 when Vance resigned and successfully ran for governor of the Old North State. The 26th was brigaded with several other North Carolina regiments under the command of Brig. Gen. J. Johnston Pettigrew.

Burgwyn whipped his young men into shape, and they acquired a reputation for discipline and prowess on the parade ground over the next year. All they lacked was combat experience. But that was about to change. In June 1863, the regiment departed with Gen. Robert E. Lee’s army on an invasion of the North. Emerson, now a lieutenant, almost missed his chance, as he was hospitalized in Richmond. He was discharged just in time to participate.

Three days after the sermon in Fayetteville, Emerson and his comrades went into action with Pettigrew’s Brigade at Gettysburg. The regiment, 843 strong, went up against Wisconsin, Indiana and Michigan boys of the Union’s famed Iron Brigade. The North Carolinians attacked across briar-choked Willoughby Run, and up McPherson’s Ridge to within 20 paces of the Midwesterners—veterans of the 24th Michigan Infantry. The two sides slugged it out among the smoke-swaddled trees in a pitched fight of mutual near-annihilation. Emerson’s Company E carried the colors in the center of a line, and was especially hard hit. Five flag bearers fell killed or wounded as they crossed the creek. Six more men who handled the colors were hit, including Col. Burgwyn, who suffered a mortal wound. The 26th ultimately succeeded in dislodging the Yankees, but at an enormous cost. By the evening of July 1, only 212 men were still standing. Of the 80-odd enlisted men of the Emerson’s company, only two emerged unhurt. Emerson somehow managed to escape injury.

Bullets struck fence posts and rails with a sound akin to “large rain drops pattering on the roof.”

The next day, July 2, Gen. Pettigrew scoured field hospitals to beef up his battered brigade. The wounded men and cooks that he found were armed with muskets, and ordered into the ranks. By this time, Company E had 12 men and a full compliment of officers: Emerson, Capt. Steven W. Brewer and 2nd Lt. Orran A. Hanner.

On July 3, the little company and the other remnants of the 26th moved out beyond the trees of Seminary Ridge as part of the 13,000-man force in the “Pickett-Pettigrew-Trimble Assault” upon the Union center. Soon, they began their long trek across the open fields, as federal artillery from Cemetery Hill on their left front sent solid shot into their ranks. Shell and case shot exploded above them. Though bloody gaps were torn into the ragged lines, Emerson and the 26th still advanced, and reached the Emmitsburg Road. There, they scaled stout fences and came within range of thousands of Union muskets. Bullets struck fence posts and rails with a sound, recalled one of Pettigrew’s men, akin to “large rain drops pattering on the roof.”

Pettigrew’s men dropped like wheat from the chaff in the vicinity of the Emmitsburg Road. Emerson continued toward the wall of stone, where Yankee muskets and field cannon roared with hellfire. In this inferno, and no more than 10 or 20 yards past the road, Emerson was struck in the thigh and arm. He fell heavily to the ground, and crawled back to the road. Second Lt. Hanner went down too, with a grievous wound to the thigh. Meanwhile, Capt. Brewer grabbed the regiment’s flag and pressed onward. After suffering a wound in the foot, he fell into enemy hands just shy of the stone wall. The attack finally disintegrated, and the survivors fell back.

Captured and treated at a Union hospital until mid-July, Emerson was transported to New York with other wounded prisoners. On July 19, they arrived at Davids Island, located in the Long Island Sound near New Rochelle. Emerson reunited with 2nd Lt. Hanner, who had been captured during Lee’s retreat, and Martha’s brother, John Yarbro, a member of the 13th North Carolina Infantry, who had been wounded on July 1, and seized the next day.

The prisoners were housed at DeCamp General Hospital, which up until the Battle of Gettysburg had treated only sick and injured northerners. Emerson and his wounded companions presented a pitiable spectacle to Union doctors after their ordeal from the battlefield to DeCamp. Augustus Van Cortlandt, acting Assistant Surgeon at the hospital, observed that they “came in a filthy, horrible condition … they were run down, and were the worst body of wounded men it has ever been my lot to see.” He added that “dirty garments were removed and burned, and new hospital clothing furnished them at the expense of the United States Government.” A fellow surgeon, George W. Edwards, reported that they “receive medical and surgical treatment in all respects equal to that of the Union soldiers,” such that the “mortality was not large.” He added that “most of the deaths occurring from the severity of the wounds.”

Emerson’s thigh wound apparently healed, but his arm became infected, and he began to suffer chills. Hanner remained with him as his life began to ebb. Likewise by his deathbed was Joe Hackney, the drum major of the 26th. A nurse known as Miss Cox had formed an attachment for Emerson, and did her best to see that he was comfortable. She and John Yarbro were in attendance as he slipped his earthly bonds at 1 p.m. on Aug. 11.

The next day, 2nd Lt. Hanner delivered the tragic news in a letter to Pat. “I can assure you that John had every attention both from physicians and nurses but all efforts proved of no avail.” He added that Emerson “only had twenty dollars Confederate money in his pocket book which I have for you … his pocket knife and comb I gave to your brother.” Pat’s grief upon hearing the news was doubtless compounded by the fact that another of her brothers, Joseph T. Yarbro of the 45th North Carolina Infantry, had also been killed. He died in action at the unfinished railroad cut during a fight against the all-Pennsylvania “Bucktail Brigade.”

The next day, 2nd Lt. Hanner delivered the tragic news in a letter to Pat. “I can assure you that John had every attention both from physicians and nurses but all efforts proved of no avail.” He added that Emerson “only had twenty dollars Confederate money in his pocket book which I have for you … his pocket knife and comb I gave to your brother.” Pat’s grief upon hearing the news was doubtless compounded by the fact that another of her brothers, Joseph T. Yarbro of the 45th North Carolina Infantry, had also been killed. He died in action at the unfinished railroad cut during a fight against the all-Pennsylvania “Bucktail Brigade.”

Emerson was buried in Cypress Hills National Cemetery in Brooklyn. He counts among the 461 Confederates who perished in captivity in New York area prison camps and hospitals—almost a quarter of whom died between July 15 and Aug. 31, 1863, as a result of wounds received at Gettysburg.

His headstone, Number 773, is intermixed among those of 3,170 Union soldiers.

References: Don Ernseberger, Also For Glory: The Pettigrew Trimble Charge at Gettysburg July 3, 1863; Ron Gragg, Covered With Glory: The 26th North Carolina Infantry at the Battle of Gettysburg; Greg Mast, “Tha Kill So Meny of Us: The 26th North Carolina Regiment at Gettysburg,” Military Images Vol. X, No. 1, July-August 1988; Raleigh (North Carolina) Standard, July 22, 1863 and July 29, 1863; Official Records, Ser. I, Vol. 27, Part II; John F. Walter, The Confederate Dead in Brooklyn; J.R. Emerson to Martha Emerson, Oct. 7, 1861, author’s collection; O.A. Hanner to “My Dear Mrs. Emerson,” Aug. 12, 1863, author’s collection; Email correspondence with John Hodge Emerson, descendant.

Charles T. Joyce, of Drexel Hill, Pa., has been a lifelong student of the Civil War and started collecting images about 25 years ago. He currently focuses on photographs of soldiers killed, wounded, or captured at the Battle of Gettysburg, and on original stereoviews taken of the battlefield.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.