By Scott Valentine

Union Capt. Samuel Miller Quincy realized that something had gone horribly wrong during the early part of the Battle of Cedar Mountain on Aug. 9, 1862.

The entire right flank of his regiment, the 2nd Massachusetts Infantry, had crumbled in the face of furious and incessant waves of enemy musketry.

Quincy endeavored to stabilize his Company E as the roar of gunfire continued unabated and the red flags of the enemy moving closer to his position. As he turned to address the men, a rebel bullet ripped into his right leg before he could utter a command. A second tore into his left foot. The double impact staggered him as his company broke and fled.

In his journal, Quincy later recalled that he was greeted soon afterwards by words that no soldier ever wanted to hear. “Surrender, G—d d–n your soul!” barked a Confederate soldier who rushed up and leveled a weapon at the captain’s head. “I gave up my sword and pistol, sat down, borrowed my captor’s knife, ripped my trousers open and shoe off, and examined damages,” Quincy wrote. “An awful hole in foot and little one in leg, at the bottom of which the bullet was plainly visible. Seeing this, the Confederate gentleman to whom I then belonged was seized with a desire to perform a surgical operation with the knife referred to, but yielded to my remonstrance and request that he would be satisfied with having put it in, and allow some gentleman of the medical staff to undertake the bullet’s extraction.”

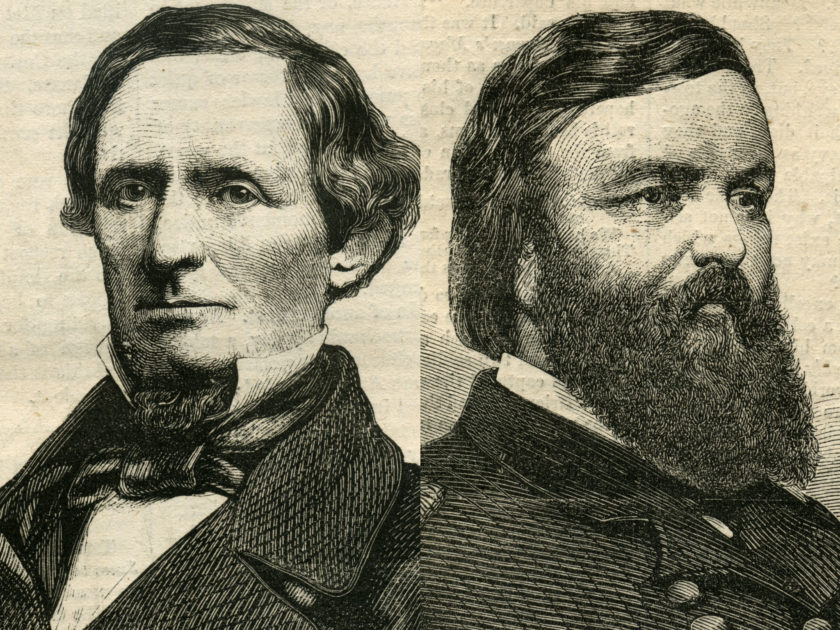

Unable to walk, Quincy slung an arm around the necks of two Confederates who carried him to a field hospital, where a mass of groaning wounded from both sides were gathered. Here, a Confederate surgeon bound up Quincy’s foot and assured him that an amputation was not necessary. After a dismal rainy night, he was transported by ambulance to the headquarters of the victorious Confederates. He expected to be interrogated by Maj. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson. Instead, he came face to face with Brig. Gen. A.P. Hill, whose plucky division had distinguished itself yet again in battle.

Quincy recalled that Hill poked his head into the ambulance. The general was all business.

“What regiment?”

“Second Massachusetts.”

“Let’s see, Gordon’s old regiment?”

“Yes.”

“Best regiment in Bank’s army; cut all to pieces though: I’ve been all over the ground.”

Hill abruptly exited, and ended the brief encounter.

Hill had spoken accurately. The original commander of the 2nd, Col. George H. Gordon, had known Hill when both were cadets at West Point. A few months earlier, in June 1862, Gordon received his brigadier’s star and was elevated to brigade command. About the same time, a reorganization of federal forces in the region produced a new 47,000-strong Army of Virginia headed by Maj. Gen. John Pope. One of Pope’s subordinates, Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks, commanded a third of the army, including Gordon’s Brigade and his old regiment.

Hill’s observation that the 2nd had been “cut all to pieces” at Cedar Mountain was also correct. In fact, the Massachusetts boys suffered 173 casualties, or 35 percent.

Quincy left Confederate headquarters in the same ambulance in which he had arrived, and endured an 8-mile journey over rocky roads and through rivers. Then, he and others were loaded onto train cars for a ride that, Quincy noted, “with occasional wakings to a semi-consciousness of rumbling wheels, brakes, and once familiar railroad sounds, mingled strangely with groans, cries, stench, squalor, and misery.”

“They took the two Yankee captains, in almost an upside-down position, with heads in straw and feet in air, through the town to the hospital…”

Quincy and his comrades arrived in Staunton, Va., to the jeers and insults of citizens. Their captors handled them roughly as they were herded off the train like so many cattle. Quincy referred to himself in the third person when he recalled his removal from the train. “They took the two Yankee captains, in almost an upside-down position, with heads in straw and feet in air, through the town to the hospital, women coming to the windows with various expressions of countenance, pity being the scarcest. I’ve often seen them look out to see soldiers pass, but never expected to figure in this sort of pageant of their edification.”

The extreme abuse had its roots in a tit-for-tat battle of orders between Gen. Pope and Confederate President Jefferson Davis.

During the run-up to Cedar Mountain, as Maj. Gen. Pope advanced his new army south, he learned from intelligence reports that the civilian population aided Confederate guerillas. Pope issued a series of orders aimed at breaking the resistance. One directive, General Order No. 7, denied guerillas the right to be treated as soldiers and instead be treated as spies and hung.

Davis responded with his own order on Aug. 1, the gist being that any of Pope’s officers who were captured would be treated not as prisoners of war, but as hostages subject to execution in retaliation for like treatment of guerillas taken by the federals.

Quincy related that had he known of Davis’ order, he would have lain down and played possum until the rebels had gone and then limped back to his own lines. He was held in Staunton from Aug. 11 through mid-October, when he discovered from a Richmond newspaper that President Davis had rescinded his order. Quincy immediately demanded his rights as a prisoner of war, and requested to be transferred to an appropriate facility. His captors complied and sent him and other prisoners to Libby Prison in Richmond.

They arrived at the infamous prison on Oct. 17, 1862. Quincy recalled that they “sent us to the hospital department, up three flights—immense room in large tobacco warehouse, lighted with a single dip, which only made darkness visible. A ragged young nurse, with his hair on end, welcomed us to the scene of despair. We were put on cots of sacking, with nothing under or over us, and shivered ourselves into oblivion.”

“We’re going home, we’re going home, we’re going home to die no more!”

Fortunately for Quincy, his imprisonment was remarkably brief. Two days later, on Oct. 19, he was handed his parole and promptly sent by wagon to a river crossing. There, he limped aboard a flag-of-truce boat. He and another released prisoner stood by the boat rail and sang in low voices, “We’re going home, we’re going home, we’re going home to die no more!”

Before long, Quincy was in Washington, D.C., and checked into one of the finest hotels in the capital. He wrote in his journal, in big letters, “A free man at Willard’s.” He added, “The next day, I drew my pay and replaced my ragged blouse, bullet-pierced trowsers, and torn Confederate cap (given me on the field to replace my broad-brimmed felt, which a Georgia gentleman fancied), by the jauntiest uniform clothes I could find.”

His new and improved look was more in line with the trappings of the Harvard-educated Boston blue blood. Descended from Revolutionary War patriot Samuel Adams and former presidents John Adams and John Quincy Adams, his father was Josiah Quincy Jr., a former mayor of Boston. His family also included a number of individuals active in the abolitionist movement.

Quincy soon rejoined the 2nd with a promotion to major. He advanced to colonel in January 1863. The pain of his old Cedar Mountain wounds prompted his resignation in June 1863, about a month before the regiment fought at the Battle of Gettysburg, where it suffered heavy casualties along Culp’s Hill during the third day of the engagement.

In late 1863, Quincy returned to the army as lieutenant colonel of the 73rd U.S. Colored Infantry. He mustered out of the army in Louisiana on Nov. 30, 1866, as colonel of the 81st U.S. Colored Infantry. President Andrew Johnson approved a brevet, or honorary, rank as brigadier general.

Quincy served briefly as mayor of New Orleans, and later as an alderman in his native Boston. He was also a noted legal author and a member of the Massachusetts Commandery of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States. His accomplishments belied his precarious health, which had never been fully restored after his Cedar Mountain wounds. He died, unmarried, at age 54 in 1887.

References: Samuel A. Bent, Eulogy on Samuel Miller Quincy; James G. Hollandsworth, The Louisiana Native Guards: The Black Military Experience in the Civil War; Robert K. Krick, Stonewall Jackson at Cedar Mountain; Samuel M. Quincy, History of the Second Massachusetts Regiment of Infantry: A Prisoner’s Diary: A Paper Read at the Officers’ Reunion in Boston, May 11, 1877; Samuel M. Quincy, A Manual of Camp and Garrison Duty; Alonzo H. Quint, The Record of the Second Massachusetts Infantry, 1861-1865.

Scott Valentine is a Contributing Editor to MI.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.