By Ronald S. Coddington

In the maelstrom of fighting at Stones River on the last day of 1862, dense clouds of gun smoke hung like a pall over the bloody battlefield.

At times, the smoke would drift apart to reveal a brief glimpse of the desperate struggle between blue and gray. At one such moment, a federal soldier observed a Union captain drop his sword, grab cartridges and a musket from a fallen comrade, and blast away at the enemy.

The event would be recorded in an after-action report as a remarkable act of bravery.

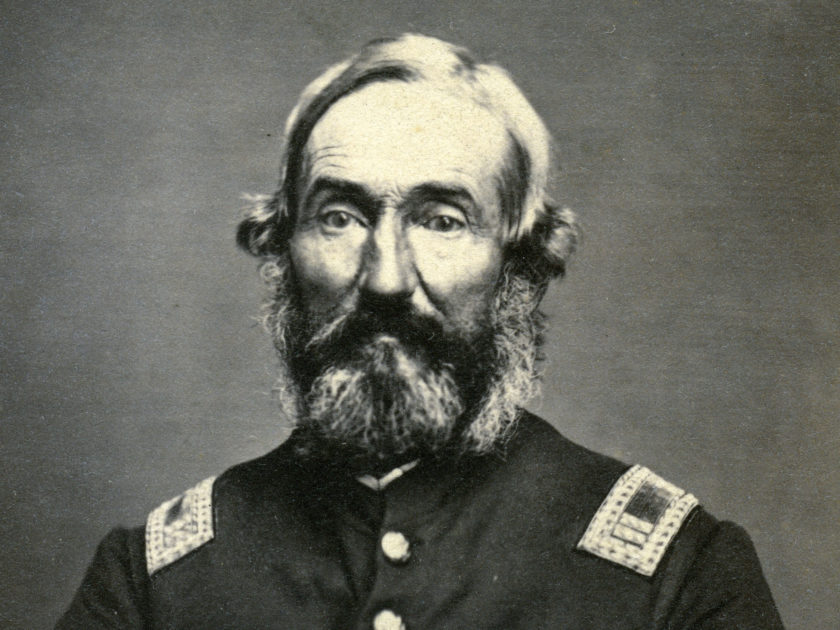

The captain, 54-year-old Richard M. Waterman of the 31st Indiana Infantry, was old enough to be the father of many in his command. A kind-hearted disciplinarian, he drove his company with characteristic determination to hold a little patch of battleground he had been ordered to defend.

Early that morning, Waterman and the rest of the 31st stirred from a restless night’s bivouac on the cold Tennessee ground in the vicinity of a cedar wood known to locals as Round Forest. Meanwhile, Union Brig. Gen. Charles Cruft, whose brigade included the 31st and three other regiments, received orders to advance.

Cruft arrayed his force in two lines. The 31st occupied the main line with the 2nd Kentucky Infantry on its left. The 1st Kentucky and the 90th Ohio infantries took up a position behind them. Cruft estimated that “The brigade, by this formation, exhibited a front of, say, 600 men.” Skirmishers fanned out ahead of the main line. Additional federal brigades were stationed to the left and right.

Cruft advanced his skirmishers at a run into a field, where they soon engaged enemy skirmishers. Behind these Confederates lay a full brigade of battle-hardened Mississippians under the command of Brig. Gen. James R. Chalmers, who had fought well at Shiloh earlier in the year.

The Confederate skirmishers drove their federal counterparts back across the field. Cruft shifted his front line back to the edge of the cedar woods. With little time to spare, the federals readied for an assault from the main body of Chalmers’s Mississippians. According to the historian of the 31st, the Indianans “laid down their guns and went to work, and in a few minutes you would have thought that every man was a natural-born stonecutter, and that each one was a master-builder. A rail fence in our front was thrown down, and by the time our skirmishers were driven in, our position was next to impregnable.”

Armed with his sword and a pair of revolvers, Waterman steadied his men before the advancing Confederates.

“The enemy pushed toward us rapidly, and charged my line in great force and in solid rank,” Cruft later reported. “His charge was made in two lines, with the appearance of a four-rank formation, and in admirable order and discipline.”

The federals returned fire with deadly accuracy and inflicted heavy casualties, forcing the Mississippians to withdraw a short distance and reform. Among the Confederate wounded was Chalmers.

“After the first repulse, and before my line could be advanced, the enemy made a second charge (reserving fire until a close approach was had), which was more furious than before,” Cruft recalled.

The Mississippians fired volleys that ripped into the Indiana and Kentucky ranks. The Union troops responded with their own well-aimed musket fire, as the fighting escalated to a fever pitch. With ammunition running low, the surviving Indianans spent precious seconds scrambled among the dead and wounded for spare cartridges. It was during these tense moments that Waterman likely swapped his sword for a musket and joined in the melee.

After a half hour of ferocious battle, Chalmers’s crippled brigade retreated in confusion. The area before the 31st became known as the “Mississippi Half Acre,” in recognition of the large number of dead that blanketed the battlefield.

Cruft took advantage of a brief lull in the action to send forward one of the regiments in his rear line, the 1st Kentucky. The men advanced into the open field and were hit hard by enemy infantry and artillery fire. The Kentuckians rolled back with considerable losses.

By now, another Confederate brigade had moved up to replace Chalmers’s badly cut up force. The brigade was composed of Tennessee regiments led by Brig. Gen. Daniel S. Donelson, which promptly advanced against Cruft. Waterman and the rest of the 31st hit the Tennesseans with a furious fusillade and drove them back. But Donelson’s troops were not finished. The Confederates changed their point of attack and launched another assault that flanked the federals. The 31st fell back through the dense woods and scattered as the fighting continued unabated. One Hoosier later recalled, “The rattle of battle being so terrific that it was difficult to make yourself heard.”

The gains by Donelson’s brigade however, were temporary. Other Union forces joined the fray and ultimately repulsed the Confederates.

Waterman and some of his men became “surrounded in the cedar thickets,” according to a newspaper account. “When he was satisfied that his capture was a certainty he pulled his shoulder straps off and hid his sword and side arms, and claimed to be a hospital steward.” The article noted, “His action was considered no reflection upon his bravery, but was always considered sharp by his fellow officers, as the rebel authorities were at that time giving union officers very harsh treatment.”

Waterman was more than qualified to fill the brogans of a hospital steward. Three decades earlier, he had graduated from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia. Some might have expected him to return to his native Rhode Island to practice medicine. Instead, he went west to Vicksburg, Mississippi. “Slavery turned him bitterly against that section,” an Indiana county historian reported, after which, Waterman relocated to the Hoosier State.

“Southern secession caused his anti-slavery principles to assert themselves.”

Waterman became a physician in Vermillion County, Ind. He married, started a family, and became an influential resident in the township of Eugene, about a day’s ride by horse to Terre Haute. In 1857, he moved to adjacent Fountain County, and became a prosperous businessman dealing in grain, pork and dry goods.

The outbreak of war stirred Waterman’s passions. “Southern secession caused his anti-slavery principles to assert themselves,” noted the Indiana county historian. He also predicted that, “the war would end when the negroes were freed.”

In the summer of 1861, Waterman recruited men for a local infantry company known as the “Wabash Rifles.” The recruits included his eldest son, Robert. The rank and file voted for officers, and elected Waterman as second lieutenant. Although he had not intended to serve as an officer, he could not refuse the honor.

The Wabash Rifles became Company A of the 31st. The regiment’s original colonel was Charles Cruft. In the fall of 1861, the 31st moved into Tennessee, and participated in the Union victory at Fort Donelson in February 1862. Two months later at Shiloh, the regiment suffered 142 casualties in hard fighting. By this time, Waterman had advanced to captain, and Cruft had left the regiment with a brigadier’s star and command of a brigade.

In the Battle of Stones River, the 31st suffered 87 killed, wounded and captured. Waterman and about 36 others fell into enemy hands. The Confederates believed Waterman’s claim as a hospital steward, and grouped him with the enlisted men. But any hopes he had had for better treatment as a private went unrealized.

“I … was carried all over the southern country, and finally landed in the prisons of Richmond, naked and half starved,” he wrote.

After traveling for three weeks, he arrived in Richmond on Jan. 21, 1863. Confederate authorities released him five days later, and sent him across federal lines to Camp Parole in Maryland in a prisoner exchange. Shortly after, he was hospitalized.

Four months passed before Waterman was healthy enough to rejoin the 31st, now encamped in Tennessee, about eight miles from the Stones River battlefield. According to a fellow officer, Waterman returned to the scene of his capture once or twice in search of his sword and revolvers, which he had secreted beneath a log in the cedar thickets. He failed to find either item.

In September 1863 at the Battle of Chickamauga in Georgia, Waterman suffered a debilitating gunshot wound in the hip. The injury ended his combat effectiveness, and further compromised his already precarious health.

When Cruft learned of Waterman’s situation, he appointed him to his staff as an aide de camp, and assigned him to light duties, which included stints as a recruiter and a military railroad conductor. Despite Cruft’s efforts to shield him from the rigors of life in camp, however, Waterman’s health further declined.

Waterman resigned due to disability, and returned to Indiana on Aug. 17, 1864. “I’ve come home to die,” he reportedly told his family. The old soldier made good on his statement six days later. He passed away a few months short of his 56th birthday.

One Indiana historian paid tribute to Waterman: “Out of the pain and death of him and thousands of other braves came the perpetuity of a great government.”

Seventeen years later, in the autumn of 1881, an Illinois druggist touring the battlefield of Stones River found a sword inscribed “R.M. Waterman, 31st regiment I.V.M.” (Indiana Volunteer Militia) hidden beneath some bushes.

The saber was eventually returned to Waterman’s son, Robert.

References: The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies; John T. Smith, A History of the Thirty-First Regiment of Indiana Volunteer Infantry in the War of the Rebellion; Richard M. Waterman military service record, National Archives and Records Service, Washington, D.C.; Hiram W. Beckwith, History of Fountain County Together with Historic Notes on the Wabash Valley; Hoosier State (Vermillion County, Indiana), November 2, p, 1881; Donald L. Jacobus and Edgar F. Waterman, Descendants of Richard Waterman of Providence, Rhode Island, Vol. III; Harold L. O’Donnell, Eugene Township (Vermillion County, Indiana): The First 100 Years 1824-1924.

Ronald S. Coddington is editor and publisher of MI.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.