By Katharina Schlichtherle

On the evening of May 31, 1862, the men of the 4th North Carolina State Troops who remained standing, after their baptism of fire in the battle of Seven Pines in Virginia, were exhausted, stunned and reeling from the staggering losses the regiment had sustained over a brief few hours taking Casey’s Redoubt, a stronghold central to the Union line. Of the 678 men the unit had carried into action that day, 324 lay dead, dying or wounded, on the field or in one of the many hospitals in nearby Richmond. For 77, attempts at saving them came too late: they had been killed on the field in the murderous enfilading fire as they advanced on the redoubt.

One of the shaken survivors was Ordnance Sgt. William Sharpe Barnes of Company F, who had turned 19 in April. It was now his painful responsibility to write home to his mother and four younger siblings on the family farm in Saratoga, Wilson County, N.C., of the dreadful news that his older brother, Jesse, was among the dead. Jesse Sharpe Barnes, a 23-year-old lawyer, had been the captain of Company F, and had died leading his men up to the breastworks of the redoubt.

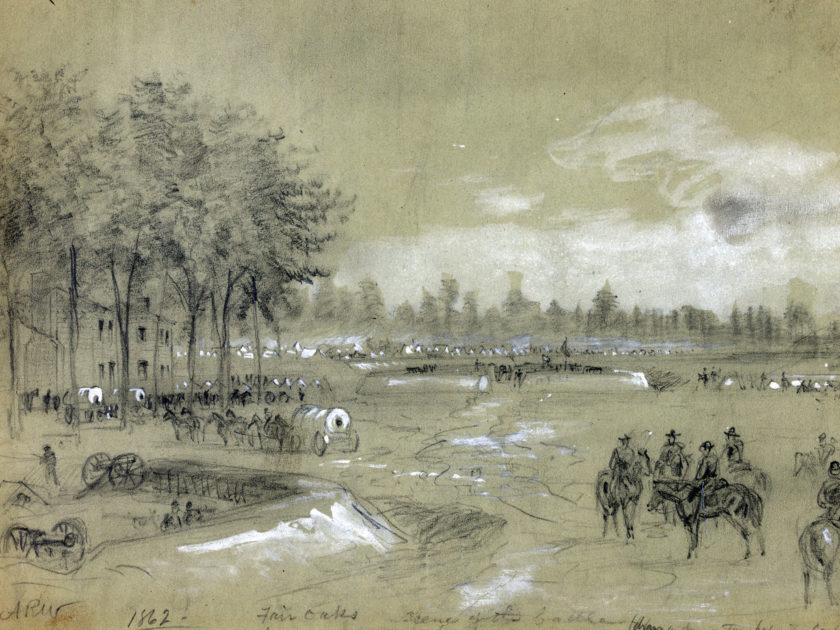

The Battle of Seven Pines, part of the Peninsula Campaign, marked the end of Union offensive operations launched two months earlier by Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan. Though the casualties were the highest of any engagement in the East up to this time in the war, the number was relatively small compared to the bloodletting that was to come. Losses on a scale unheard of—numbers previously unimaginable—would soon obliterate the death of one young man from rural eastern North Carolina.

But for the Barnes family, the news came as another heavy blow. Mahala Sharpe Barnes, a widowed mother of 10 children, had lost three offspring in 18 months. In addition to Jesse, her 26-year-old son, John, a private in the 7th Tennessee Cavalry, died of disease in a Kentucky camp. She also suffered the death of a daughter. Only seven siblings now remained, with William and the oldest son, Benjamin, serving in the army. Another brother, Joshua, would be conscripted in 1864, after he turned 17. Fortunately for the family, these three brothers survived the war.

Born on June 18, 1838, Jesse Sharpe Barnes was the fourth child of affluent farmer Elias Barnes and his wife, Mahala. This particular Barnes family was a branch of one of the more influential families in the Stantonsburg/Wilson area, then part of Edgecombe County, N.C. One of Elias’ brothers, Joshua Barnes, was a militia brigadier who, in 1849, was involved in incorporating the town of Wilson, and, in 1855, a county by the same name. A prominent supporter of local education, he was instrumental in incorporating the Toisnot Male Academy and the Wilson Female Seminary. Education was important to Elias as well, who served as a trustee for the Hopewell Academy. Another brother, William Barnes, was a successful lawyer and planter. All three brothers were among the area’s larger slaveholders, with Elias Barnes holding title to 56 slaves in 1850. According to Elias’ will, the family farm was roughly 500 acres in area. The number of slaves and amount of land owned by the Barnes family put them in the top 3 percent of all North Carolina households—one of the state’s elite clans.

“Civil discord—the blighting breath of Fanaticism, and the dreadful spirit of Sectionalism, have all striven to drag down this mighty temple of Liberty.”

In this affluent and privileged setting, Jesse and his nine siblings, all born between 1831 and 1855, grew up. And, their expectations of life were surely formed by it. All the Barnes children, during and after the Civil War, received the best education available at the local level. Benjamin went on to complete his education at the University of North Carolina, where he enrolled in 1852. Two years later, Jesse, now 16, followed his brother to Chapel Hill. The family could well afford this prestigious option, rather than sending the brothers to a less costly sectarian college. At the time, state universities were seen as providing the education needed to take leadership roles in society, and possibly paving the way to fame and fortune. The University of North Carolina, like other institutions of higher education, attracted wealthy sons of the Southern gentry.

Both Barnes brothers were active in the Philanthropic Society, and numbered among the better students in their classes. Jesse was serious about his studies, especially his oratory skills. At the end of his first year, he was one of a select group of freshmen invited to participate at the declamation during the commencement ceremonies. Jesse participated again in his sophomore year, though his educational accomplishments began to drop off. The decline coincided with the sudden death of his father, who was fatally struck by lightning on June 6, 1856. Jesse however, did graduate on track in 1858, and became an attorney, specializing in property and equity law in Wilson.

Jesse delivered a required oration at his commencement. He entitled his speech, “What we, as a nation, have been and are.” In it, he recapped the fight for freedom from Great Britain, and extolled the progression of the newly formed nation, resting secure on “that mighty instrument which stands as a noble monument of the deep penetration and wise discernment of the giant minds that framed it”—the U.S. Constitution. Jesse went on to acknowledge that, in addition to outside powers, “other things, far more dangerous, have threatened to poison the healthful food of millions. Yes: civil discord—the blighting breath of Fanaticism, and the dreadful spirit of Sectionalism, have all striven to drag down this mighty temple of Liberty; but we may rejoice that they have as yet utterly failed.” Jesse ended the speech with patriotic fervor: “It becomes our highest duty to endeavor to protect and hand down pure and uninjured to our posterity this union and its constitution so that they may, as you or I would now, glory to stand upon some lofty pinnacle, with the whole world in view and proclaim to it in thunder tones, I am not only an American but a citizen of these United States.”

Clearly, in the spring of 1858, Jesse held pro-Union feelings. Yet by late 1860, with sectional tensions exacerbated by John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry, Va., Jesse transformed into a staunch secessionist.

How, in the span of not even three years, did his beliefs change so drastically? The answer lies in his upbringing and the changing political climate, as well as his personal situation. Following the death of his father, he inherited valuable slaves. In 1860, he held title to six slaves, and hired some out to work for additional income. Jesse’s personal property was valued at $7,000 in the 1860 census. Before the presidential elections in November 1860, he likely still held hope for a Union under a government that would protect the right to own slaves. Politically ambitious, Jesse threw his support behind the Southern Democratic ticket of John C. Breckenridge and Joseph Lane. He also campaigned for the Democratic candidate in Wilson County. Jesse’s involvement indicates that he believed slavery should be maintained, and possibly even expanded.

The election of Republican presidential candidate Abraham Lincoln prompted the southern states to secede and take up arms. Jesse followed suit. The only known photo of him shows him attired in a South Carolina militia uniform. Evidence suggests he enlisted in a South Carolina militia company soon after the state seceded on Dec. 20, 1860.

Jesse was not the only North Carolinian to offer his services to the Palmetto State. At least three other young men from Wilson likewise did the same, including Jesse’s cousin Lafayette Barnes.

“Jesse now favored immediate secession from the Union.”

Jesse’s tenure in the South Carolina militia was brief. He was back in North Carolina by February 1861, where he campaigned for his home state to sever its ties with the Union. On Feb. 12, 1861, at a convention of the people of Edgecombe County in Tarboro, N.C., Jesse delivered a well-received speech, “favoring immediate secession, disapproving any Constitutional compromise that shall not recognize slavery in toto as a social blessing.” He perceived Lincoln’s election as a threat to what he considered the only right social order, as well as to his personal property and interests. At this point, the general sentiment in North Carolina overall was still pro-Union. Two weeks later, a slim majority of voters rejected a proposal for a secession convention. But the secessionists, who continued to campaign and prepare for the state’s secession, carried the eastern coastal counties, and those such as Edgecombe or Wilson, with their tobacco plantations and large slave populations. Once Fort Sumter was bombarded and President Lincoln called for volunteers to put down the rebellion, the tide in North Carolina turned in the secessionists’ favor. The state left the Union on May 20, 1861.

Meanwhile, weeks before North Carolina seceded, Jesse recruited men for the Wilson Light Infantry, a militia company that mustered into service on April 18, 1861. Jesse was appointed captain a month later. Among those who joined the unit were Jesse’s barely 18-year-old brother William, his cousin Lafayette, his mother’s farm manager, William Meeks, and several other cousins. The Wilson Light Infantry was among the militia units ordered to seize Fort Macon, where they arrived on April 19.

Army life for the young men was light-hearted, as they enjoyed being on the seaside – shooting porpoises or running from imaginary sharks, broken only by the occasional false alarms about Union warships. The men were itching however, to enter regular service. Through their captain, they petitioned Gov. John W. Ellis for help.

The men were soon called to arms. At the end of June 1861, they arrived in Garysburg, N.C., where they mustered into Confederate service as Company F of the 4th North Carolina State Troops. The regiment soon received orders to report to Virginia. On July 21, the unit arrived near Richmond, and enjoyed the cheerful welcome and hospitality of the ladies.

In the interim, approximately 100 miles north at Manassas Junction, Va., the first major battle of the war was fought and won by the forces of the fledgling Confederacy.

Jesse and part of the 4th arrived at Manassas Junction shortly after the battle, with the remainder of the regiment following at a later date. The 4th remained here for eight months, guarding prisoners and provisions. Tours of the battlefield exposed them to the cost of war, as they viewed the fresh graves of their fellow Confederates and half-buried bodies of Yankees. Disease ravaged the regiment and accounted for the deaths of at least nine men in Company F. A task fell to Jesse to write letters of condolence to grieving families back in Wilson. One of these letters was to his widowed aunt, Theresa Barnes, informing her that her youngest son, Lafayette, a sergeant, had succumbed to typhoid fever late in October.

Jesse wrote letters on other matters that involved the men of his company. After Pvt. Malachi Williams accidentally shot and killed fellow Pvt. Ed Bridgers, Jesse became so worried about the soldier’s mental state that he talked to him for hours, and later reported to Malachi’s father that his son had at last reconciled himself to the fact that the incident had been a terrible accident. In another letter, he assures the worried father of underage Pvt. George Battle that he would “as heretofore, advise and correct him and use every effort in [his] power to secure his happiness and welfare.” Tragically, George was killed in the same battle as his captain, who had promised to take care of him as best he could.

Jesse took his responsibility for the men seriously, and became a popular and respected company commander. George had previously written to his parents noting that whenever Jesse left the camp for a stretch of time, they looked forward to his return, and were “all very glad to see the captain.” Jesse left Manassas Junction on at least two instances. In early October, he traveled to Wilson, from where he returned with letters and gifts from families at home, and sending everything he could not carry by express at his own expense, endearing himself to his men. He also paid for another luxury for himself and the men: supplemental whiskey rations. Additional responsibilities of a more military nature were placed on his shoulders when he assumed command of two batteries in November 1861. By that time, winter huts were under construction and everyone had settled into life in an army camp. On Jan. 19, 1862, Jesse received a furlough and returned home to Wilson to recruit men for his company. On the way back from his furlough, Jesse appears to have stopped in Richmond to witness the inauguration of President Jefferson Davis on Feb. 22, 1862.

Jesse’s stay in Manassas ended in March 1862, when the regiment and other troops pulled out to participate in the Peninsula Campaign. The 4th defended Yorktown, but saw little action beyond picket duties, during which at least a few men received their first whiff of being shot at and returning fire. Here, on April 15, Jesse made out his one-page will. In it, he noted, “I give my soul to my God, my body to the dust from whence it came, wishing however if possible to have it interred in the family graveyard at my mother’s in Wilson County.”

About three weeks later, his will almost took effect after he contracted typhoid fever. Treated at Chimborazo Hospital No. 3 in Richmond, he recovered and rejoined his regiment one week before the battle that would be his first and last.

By all accounts, that final week of his life was of little rest, as the 4th remained on constant alert. A cyclical routine of slogging through rain and mud, falling into line of battle, and digging rifle pits tested everyone. The night before the battle proved particularly dismal. The men and officers spent a sleepless night close to the enemy lines, pelted by rain with only blankets to protect them, and keenly aware that a major engagement was at hand.

What was Jesse doing on that night? Did he chat with his brother or write home to their mother or a sweetheart? Did he talk to his men, maybe sharing jokes and stories to lighten the atmosphere? Was he excited despite the cold and wet? These questions remain unanswered.

The storms finally broke, and May 31 dawned sunny and humid. By this time, the North Carolinians were already on the march. Later that day, they were ordered to stack arms in a wooded area, expecting to be held in reserve. But different orders arrived: prepare for a fight.

The commander of the 4th, Col. George B. Anderson, led his men toward the Old Williamsburg Road under heavy fire from federals that occupied a section of line known as Casey’s Redoubt. The route took them through terrain that had turned into swampland by the rains, and some wounded men drowned in waist-high water. The rest of the regiment struggled on through a tangle of abatis while under artillery fire.

Then, the North Carolinians charged across an open field under a hail of grape and canister. Jesse and Company F occupied the center of the regiment’s line. Yankee lead churned up the ground around them as they raced across the clearing, leaving large gaps in the line. The men closed ranks as best they could. Confusion and lack of support caused them to fall back, despite their having almost gained the redoubt. They rallied, received reinforcements, and charged again, and this time took Casey’s Redoubt. During this second assault, Jesse likely fell while leading the remnants of his company, and, according to one of his soldiers, “just as we captured the guns.” Ten more men of Company F lay dead on the field. Several others subsequently died of their wounds or were permanently disabled.

William Barnes had lost his older brother, who had always looked out for him. Now, it was his turn to look out for Jesse and make sure that his last wish, to be buried at home, would be fulfilled.

Maj. Bryan Grimes, who wrote the official report of the 4th at Seven Pines, singled out only two men of the many that had engaged in the fight: “No braver men died that day than Captain Barnes of Company F, and Lieutenant White, of Company C, who were killed while leading their men up to the breastworks.” Edwin A. Osborne, who served as captain of Company H during the battle and later became the regiment’s colonel, eulogized Jesse in a postwar sketch: “He was a splendid young officer of great promise; a most intelligent, genial and promising man; a man of education, young and talented; a good soldier, and very highly esteemed in the regiment.”

Jesse Sharpe Barnes was a product of the society and times he grew up in, an essentially decent man who supported a terrible institution. And as so many epitaphs etched on Confederate grave markers attest, he fought for his beliefs and paid the ultimate price.

Brother William carried out Jesse’s last wish and arranged to bring his remains home—one of only three men from the regiment who died at Seven Pines to return to their loved ones. Jesse now rests in the family cemetery. Jesse’s gravestone speaks not of beliefs, but of loss and the eternal hope of reunion:

Sacred to the memory of Two Brothers

John P. Barnes

Born Dec. 14, 1835

Died Dec. 15, 1861

At Camp Desha, near Moscow, Ky.

His remains are at Elmwood Cemetery, Memphis, Tenn.

Brother I come

Jesse S. Barnes

Born June 18, 1838

Died May 31, 1862

Being killed at the Battle of Seven Pines, Va.

His remains rest here.

They grew in beauty side by side,

They filled one home with glee.

Their graves are severed far and wide,

By Mount and Stream and Sea.

Katharina Schlichtherle holds M.A. degrees in History as well as English from Christian-Albrechts-University Kiel, Germany, and the University of Maryland, College Park. She is now teaching both subjects at the German embassy school in Oslo, Norway.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.