By Dan Clendaniel

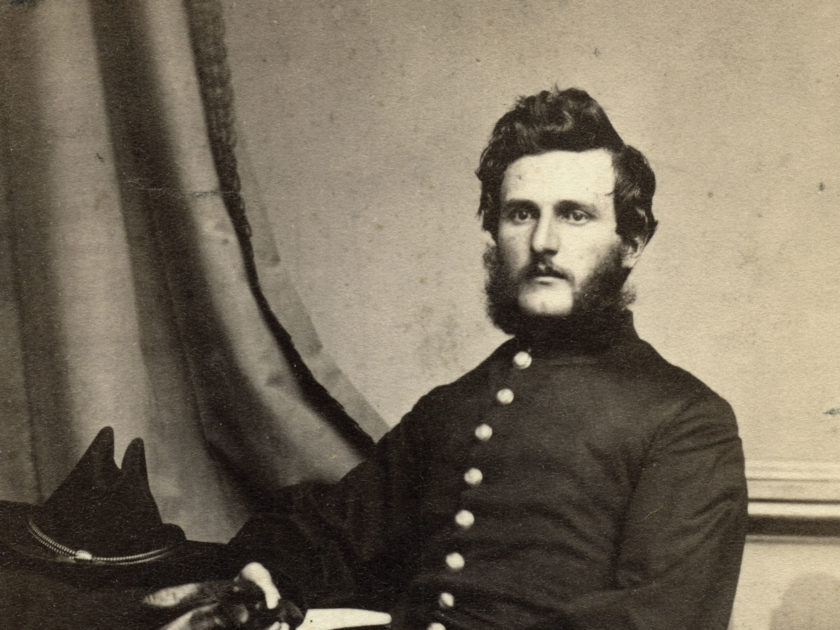

When he enlisted into the Union army, Lt. John E. Michener could not have imagined that his first armed encounter would occur in his Pennsylvania hometown.

Shortly after joining the 85th Pennsylvania Infantry in the late summer of 1861, the 24-year-old Michener was sent on a recruiting trip by his colonel, Joshua B. Howell. The destination was Michener’s home in Fredericktown, Washington County, located in the southwestern part of the state

The timing of the visit was critical. The Union had just been handily defeated at Bull Run in Virginia, and Howell, like many prominent northerners, was anxious to organize a new three-year regiment to help defeat the rebellion of southern states and restore the Union.

Michener’s trip, on Sept. 26, 1861, initially succeeded. Local pro-war speakers helped the young lieutenant gather up eight volunteers to join the regiment. The group planned to travel by steamboat up the Monongahela River to Brownsville, and then overland to Uniontown, Howell’s hometown and the site of Camp Lafayette, where the 85th trained and drilled.

As Michener prepared to board the steamboat near Brownsville at Fredericktown, a small but aggressive group of anti-war citizens voiced their opinions of Michener’s efforts.

Southwestern Pennsylvania was a stronghold of the Democratic Party, but, as in other regions of the country, secession had divided the area into pro- and anti-war factions.

Michener, ardently pro-war, encountered anti-war Dr. Alexander Patton, who soon became a Copperhead in the state legislature. Patton launched a loud diatribe against the war and the administration of President Abraham Lincoln. An argument ensued as citizens on both sides confronted each other. Offended by what he considered as unpatriotic remarks, Michener’s older brother, Ezra, jumped into the fray.

As Ezra launched into a pro-war statement, another anti-war advocate, burly James C. Burson, 35, grabbed him by the throat and knocked him to the ground. Burson’s father, 66-year-old Abraham Burson, who was also Dr. Patton’s father-in-law, lunged at Ezra with a knife and barely missed him.

Michener came to his brother’s defense, aimed a pistol in the direction of the elder Burson and pulled the trigger. But the weapon did not fire. In the heat of the moment, Michener forgot that he had emptied the weapon prior to the recruiting mission.

No one was seriously hurt in the melee.

Michener collected his wits and wisely hustled his recruits to the river, and steamed away before the fight escalated. Michener’s father, Milton, who witnessed the event, noted, “It was well the boat came when it did for I never saw such excitement.”

For Michener, the Battle of Fredericktown, as Milton named it, marked and unusual beginning to an eventful military career. A peacetime clerk, he and his wife, Priscilla, or “Cillie,” had lived in the Washington County town of East Bethlehem. Their first child, Maude, was in August 1861—about the time Michener joined the army.

After Michener disembarked his recruits from the boat in Brownsville, he took a moment to write his siblings. “I leave Brownsville on Friday morning with my recruits … If you can find any men no matter about their character (for that is all righted in camp) bring them or send them up.” He continued on with the recruits to Uniontown and Camp Lafayette, where he reunited with his comrades in Company D and the rest of the 85th. Despite Michener’s efforts, the ranks of his company and others were not completely filled. Men from nearby counties, namely Greene, Fayette and Somerset, were brought in to complete the regiment’s enlistment.

Six weeks later, in late November, the men boarded trains at Uniontown for Washington, D.C., amid a cheering throng of family members and local citizens. They soon arrived in the nation’s capital and joined other troops in Washington’s defenses.

In the spring of 1862, the 85th embarked on Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign in Virginia, designed to capture Richmond and end the war. After a few weeks of marching on muddy, rain-swollen roads in cold weather, and without adequate clothing, sickness had reduced the ranks of the regiment by nearly 50 percent. By the end of May, the 85th, part of the division of Brig. Gen. Silas Casey in the Fourth Corps commanded by Maj. Gen. Erasmus D. Keyes, had established a base at Seven Pines, six miles from Richmond and far in advance of the rest of McClellan’s army.

In this area, Michener would experience his first taste of battle.

On the night of May 30, Michener and his captain, John Horn, led their Company D to the picket line during a driving thunderstorm.

“Our little division was attacked by an overwhelming force of the enemy’s best men, and after suffering a heavy loss, was repulsed, but not until we had caused hundreds of rebels to bite the dust!”

Early the next afternoon, Confederates swept down upon Casey’s exposed division, temporarily separated from McClellan’s other three corps by the swollen waters of the Chickahominy River. The Battle of Seven Pines, or Fair Oaks, had begun.

Michener and his company put up a brief but futile resistance before retreating back to their regiment, encamped near the aptly named “Twin Houses” along Nine Mile Road.

For three hours, the 85th and the rest of Casey’s Division bore the brunt of the attack without support. His greatly outnumbered men made several stands that allowed time for Union troops to cross the Chickahominy River. The three-day battle ended with high casualties on both sides, but without a victor. Casey’s Division helped stop the Confederates from gobbling up nearly half of McClellan’s army on the south side of the Chickahominy.

McClellan singled out Casey’s men before the conclusion of the three-day battle, but not for their heroic stand. Rather, he disparaged them for the haphazard manner of their retreat. McClellan, who had remained in the rear during the engagement, relied on the flawed assessment of Maj. Gen. Samuel P. Heintzelman, the Third Corps commander who arrived late to the fray. Based on Heintzelman’s report, in which he absolved himself for the near disaster, McClellan praised all of his troops to the national press, with the noted exception of Casey’s men, whom McClellan accused of giving way “unaccountably and discreditably.”

Six days after the battle, Michener wrote home, “I have just passed safely through one of the bloodiest battles ever fought on this continent. On Saturday of May 31st, without any support, our little division was attacked by an overwhelming force of the enemy’s best men, and after suffering a heavy loss, was repulsed, but not until we had caused hundreds of rebels to bite the dust!”

Michener also described how he narrowly escaped capture. “I was on picket duty in front of the swamp, and had instructions to hold my ground till the last. The result was my retreat was cut off by being out-flanked … I resolved to ‘try the desperate chance of running the gauntlet by the Rebel picket lines.’”

Michener survived the fight, although 50 or so men from his regiment were killed or wounded. Following the battle, Casey was relieved of command, and his division banished to the rear for the duration of the Seven Days Battles around Richmond in late June.

Michener had established himself as a well thought of junior officer by the men in his company. Pvt. Milton McJunkin of Bentleyville, Pa., who was often highly critical of other officers, wrote home after Seven Pines, “Lieutenant Michener was running around among us all the afternoon. He carries a gun. He took aim at five rebs that day. He is the only officer in co D that they put much confidence in. his enemies are as scarce in co D as some mens friends are.”

Two months later, the 85th was dispatched to Suffolk, Va., to help guard the Norfolk Naval Yard. By this time, Michener had lost all faith in McClellan’s generalship. His change of heart may have been due to bitterness over McClellan’s unfair assessment at Seven Pines, and the abject failure of the Peninsula Campaign. Michener explained, “My ardent attachment for him has blinded my eyes to all his blundering errors of the past! Ye gods! What has he done? Visit the [hospitals] and there view the innumerable mounds—the unmarked spots, where rest the remains of patriotic soldiers! Then go to the battlefields of Fair Oaks, Mechanicsville, White Oak Swamp and Malvern Hill, and as you gaze upon the bleaching bones of the brave men that gave their lives to their Country, you will have an answer! He has ‘let slip’ every favorable opportunity of taking advantage of the enemy.”

Michener’s brother, Ezra, then re-emerged in the picture. He worked as an assistant to regimental sutler James Clark. From Suffolk, Ezra wrote home in the fall of 1862, “We just got our house done yesterday. John has put him up a nice little log house and has a stove in it. He lives as comfortable as he could at home. Clark and John and myself board together and we have two negroes to wait on us and to tend to the horses and coach for us and we have plenty to eat.”

In December 1862, the regiment transferred to Maj. Gen. John G. Foster’s command in New Bern, N.C. Michener was away on another recruiting mission in western Pennsylvania and missed the two-week Goldsborough Expedition to destroy a key railroad bridge. The 85th returned to New Bern with minimal casualties.

Michener rejoined the regiment in January 1863, just as it deployed to the outskirts of Charleston, S.C., to participate in siege operations against Confederate forces.

While stationed on Folly and Morris Islands, hundreds of men from the 85th and other regiments fell sick with heat exhaustion and chronic diarrhea. Michener observed in a letter home, “The greatest drawback is the water we are compelled to drink. The manner of procuring is as follows: A hole is sunk some three or six feet in the sand, when generally water is found. For two or three weeks, the water is drinkable, when through the heat of the sun or some cause or other, it smells stagnant and becomes unfit for use.”

Peace Democrats in the North, meanwhile, began to hold rallies in reaction to the slow pace of the war and Lincoln’s issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation on Jan. 1, 1863. They sought a negotiated end to the war and a formal recognition of the Confederate government.

In response, Michener penned a letter signed by each member of his company to several newspapers back home. The New York Times picked it up. Michener declared that his men summarily opposed any settlement short of southern capitulation. “While anxious for a speedy and honorable peace,” he wrote, “we have followed the torn and blood-stained colors of our regiment through too many hardships and privations, at this late hour of the contest to consent that they should all go for naught. We have no compromise to make with Rebels, except at the point of our bayonets! And sympathies with Rebels at home—under whatever guise or name—let them be sent to keep companionship with their chosen friends … For one I have no patience with southern sympathizers.”

“We have no compromise to make with Rebels, except at the point of our bayonets!”

Subsequent military and political events would ultimately prove Michener’s view dominant, though he faced challenges in his own regiment.

In early 1864, during a relatively pleasant three-month stay on Hilton Head Island, Michener undertook encouraging his men to re-enlist. He hoped that the 85th would rejoin en masse as had the other three regiments in their brigade. As a reward, these men received a cash bounty and a one-month furlough home.

Efforts to re-enlist men in the 85th, however, lagged. Only about a hundred men extended their enlistment. Michener suggested in a letter that the reason lie with the unpopularity of their lieutenant colonel, Edward C. Campbell. “We are at present making an effort to re-enlist this reg’t,” Michener wrote in January, “But I fear the men will not ‘go in’ under the present Lieut. Col. Campbell.”

The diary of Capt. Richard Dawson of Company I confirmed Michener’s evaluation. “[The] 39th Ill and 62nd Ohio have re-enlisted and gone home. 67th Ohio go on the next steamer. The 85th won’t do it with Campbell as Lt. Col. The officers have held several meetings and have all signed a paper asking him to resign … Most of the Regt. were satisfied that [if] Campbell would be out of the brigade they would go in.”

Campbell, who commanded the regiment during absences by Col. Howell, was, in fact, unpopular with most of the men. At one point, Campbell was away at division headquarters when a payroll arrived and was distributed. Incensed that the men received their wages without his authorization, Campbell had every officer of the rank of lieutenant or above, with one exception, placed temporarily under arrest. As most of the regiment boarded a transport to return home in late 1864, the enlisted men gave “three hearty cheers for those present at the dock to witness their departure followed by three groans for the lieutenant-colonel.”

In early 1864, Michener was promoted captain of Company K. His first combat assignment came after military intelligence revealed that Confederate troops in Georgia had thinned. The Georgians had reportedly been sent to Florida to reinforce Confederates defending a major incursion of Union troops under Brig. Gen. Truman Seymour.

Intelligence reports also conveyed that on Georgia’s Whitemarsh Island, 300 African Americans performed fatigue duties for the Confederates. Col. Howell took command of a small force to confiscate these men for the Union. Howell left Hilton Head Island on February 21 with Michener and most of his remaining regiment, as well as parts of the 67th Ohio and 4th New Hampshire infantries, aboard four transports.

A day earlier, Seymour’s Florida expedition ended in defeat after Confederates routed his forces at Olustee Station west of Jacksonville.

Back in Georgia, Howell and his command landed on Whitemarsh Island and scored an initial success. But they soon met stiffer-than-expected resistance in an attempt to capture a bridge leading from Whitemarsh to Oatland Island. The garrison of a newly constructed fortification put up a determined fight. Howell ordered a retreat back to the transports. While covering the withdrawal of his men from the far side of Oatland Bridge, Michener was captured along with Pvt. Eli Shallenberger of Company C and Corp. James C. Bailey of Company K.

The day after the expedition returned to Hilton Head, Capt. Rolla O. Phillips of Company D described the capture of his friend “Mich” in a letter to Michener’s family.

“I am compelled to announce an event that has made me very sad indeed. … Your brother, and mine fraternally, is missing, and a prisoner—On Sunday last, we were ordered on boat transports and sailed for Georgia by way of Fort Pulaski. [We] Landed in small boats, and about seventy of us under command of Capt. [George] Hooker went into the country to destroy a bridge—At the bridge, we found a fort. John was deployed with his company skirmishing. He was across the bridge. Our force was too small to charge, and he was notified to fall back. He directed his company to move back and he would follow … By this time, they [Confederates] had been reinforced and were raking the bridge and I think he was thus prevented from getting back. I have questioned all his men, and his first sergt. tells me he feels confident that he was not wounded.”

Howell returned to Hilton Head without the African-American laborers. He did capture about 15 Confederates, enough success for the Northern press to claim victory.

A Savannah newspaper however, reported triumphantly that “The object [of the expedition] seems to have been to capture our forces on the island and to this end the first named party sent forward a detachment of twenty men under Lt. John E. Michelor [Captain Michener] … to take possession of the bridge leading from Oatland to Whitemarsh … the lieutenant was ordered to charge with a promise that he should be supported by the entire force … Michelor displayed great daring and gallantry, but his crowd were cowardly not to back him up in the undertaking.”

Michener’s father was filled with anxiety, stating, “O my god what trouble this is.” Michener’s wife, Cillie, expressed her fears to a sister-in-law. “Oh Malinda! You don’t know how it grieved me when I heard it. It almost set me crazy to think he was wounded and in the hands of the Rebels, for I know how badly they treat our men.”

Milton, however, reflected on his son’s status as a prisoner. “Perhaps his capture will be the means of saving his life.”

Milton’s speculation may have been prophetic. While Michener was held a prisoner, the 85th returned to Virginia and fought in the Second Battle of Deep Bottom in August 1864. A third of the Pennsylvanians fell in the fight.

In April, Milton reported to his daughter, Malinda, that “Cillie got a letter from John stating that he is in Charleston in jail but well and hearty and not hurt, and that he is well treated … I believe God has answered a prayer in John’s behalf.”

In late August, Milton wrote again to Malinda. “Cillie got another letter from John yesterday written on the 11th of July stating that his health continued good.”

About this time, Michener found himself in a precarious situation when both sides began using prisoners as human shields. Angry Confederate authorities protested the continual bombardment of their city, which they claimed harbored innocent civilians. Michener was among of 50 prisoners moved to the O’Connor House in downtown Charleston where they were subjected to artillery shells from their own guns.

Union officials, meanwhile, considered Charleston a legitimate military target. In retaliation for the Northern men placed under fire, a stockade went up on Morris Island between federally controlled Fort Putnam (formerly Fort Wagner) and Fort Sumter, manned by Confederates. The federals filled it with 50 Southern soldiers.

Remarkably, hostile fire did not kill any soldiers. The situation cooled, and the prisoners were withdrawn, but only after a second round of human shields involved 600 men on each side. The Confederate prisoners were later described as the “Immortal 600.”

Michener was taken to the harbor for a prisoner exchange on two occasions. But authorities called off each release after demands by each party failed.

Meanwhile, Shallenberger and Bailey, captured along with Michener on Whitemarsh Island, shuttled among various prison camps, including the infamous Andersonville facility in Georgia. Shallenberger survived captivity and was exchanged 10 months later. Bailey also survived, but died on a Union hospital ship during his return trip to the north.

Michener remained captive for eight months. On Oct. 16, 1864, he was exchanged for a Mississippi cavalry captain, Alonzo J. Lewis, captured in a skirmish near Port Hudson, Miss, in February 1864. The exchange took place at Cox’s Landing on the James River in Virginia.

Shortly after the war, Michener penned a letter on behalf of an order on Catholic nuns, the Sisters of Mercy, which had helped care for Union prisoners during their captivity in Charleston. Michener wrote to the head of the order, Sister Xavier, “I met you and your noble Sisters in the hospitals and the prisons administering to the wants and comforts of my fellow prisoners by furnishing them not only with proper food, nourishment, etc. but even clothing to those who were destitute. I also witnessed the noble sacrifice you made in nursing our sick during those days when yellow fever was carrying off our best officers and men … I know full well that but for your untiring devotion to our helpless officers and soldiers, thousands today would have been sleeping the sleep that knows know waking.”

Michener returned home to Pennsylvania in late 1864 and reunited with his family. Following the war, he worked as a clerk in Washington, D.C. He died in 1879 at age 41 from lung disease, and was buried in the Fredericktown Cemetery in Washington County. His wife and four children survived him.

Six months after his death, Post 173 of the Grand Army of the Republic in Brownsville was named in his honor.

References: Margaret Thompson, Michener and Thompson Family Civil War Letters; Ronn Palm, Richard Sauers and Patrick Schroeder, The Bloody 85th: The Letters of Milton McJunkin, a Western Pennsylvania Soldier in the Civil War; Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, The New York Public Library Digital Collections; Luther Samuel Dickey, History of the 85th Regiment Volunteer Infantry, 1861-1865; Daily Evening Bulletin, Harrisburg, Pa., Sept. 12, 1863; Savannah Republican, Feb. 23, 1864; Official Records; John E. Michener letter to Sister Xavier, April 6, 1869, Petition from the South Carolina State Legislature; Richard W. Dawson Diary, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University; National Register of Historic Places, U.S. Department of the Interior.

Dan Clendaniel of Manassas, Va., is working on a history of the 85th Pennsylvania Infantry. His great grandfather, John Clendaniel, and great granduncle, Stephen Clendaniel, served with Michener in Company D.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.