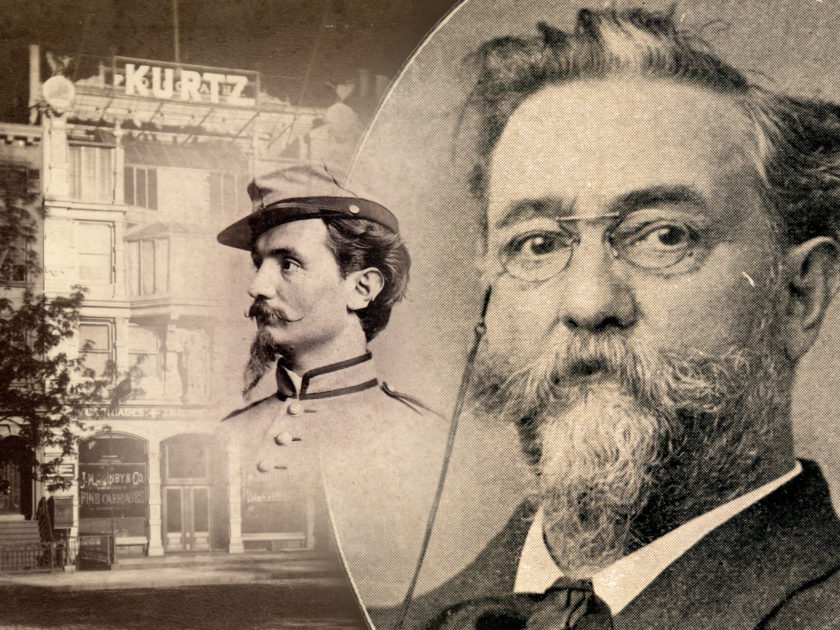

Accidental American, Soldier, Artist, Photographer: The notable journey of Civil War veteran William Kurtz

By Scott Valentine

Individuals from all walks of life made their way to the United States in the middle of the 19th century. Many landed in the young Republic eager to make something of themsel