STORIES OF PATRIOTISM

“Go With Me Into This Great Fight for the Dear Life of the Nation”

Chaplain Andrew Leete Stone cared for wounded soldiers of his 45th Massachusetts Infantry while the Battle of Kinston, N.C., raged around him. Fear gripped him in the midst of shot and shell. During this awful moment, he recalled the words of Christ to Pontius Pilate in Chapter 19 of the Book of John: “Thou coulds’t do nothing at all except it were given to thee from above.”

The passage soothed his soul. “If death comes while doing my duty it is all right for I would fall at my post,” he thought.

Stone shared this personal anecdote in a sermon to the survivors of the regiment days after the Dec. 14, 1862, battle. The courage to tell his story added to the admiration and respect he already enjoyed.

Courage had always been part of Stone’s character. A native of Connecticut who graduated from Yale in 1837 and studied at Union Theological Seminary in New York City, he was an ardent abolitionist. He railed on the subject from the pulpit of Park Street Congregational Church in Boston, Mass. “Dr. Stone early took in this city a bold stand as a Reformer in the days when it cost something to attack slavery and public wrong,” stated one of the church members.

This writer and 79 other churchmen enlisted in the Union army in the summer of 1862. They composed the majority of Company A of the newly formed 45th. They signed up at Rev. Stone’s request: “Go with me into this great fight for the dear life of the nation.”

The 45th spent the majority of its 9-month enlistment in eastern North Carolina fighting to secure the region for the Union. Chaplain Stone’s gifts of communication inspired the men. “He was always brief, never wearisome, rarely occupying more than twenty minutes in the delivery of his sermon. He had a fine presence, a wonderful voice, and a great ease in his delivery,” noted the congregant who went off with him to war. The Battle of Kinston proved the regiment’s costliest fight, with 58 killed and wounded.

The 45th spent two months on provost duty in nearby New Bern. Stone’s wife, Matilda, joined him and opened a school for 500 children of color. He established a school for freedmen.

The regiment returned to Boston at the end of its tour of duty and Stone rejoined his congregation. In 1866, he left for a new post in San Francisco. In an emotional farewell speech, he thanked his flock for its war service: “Oh, had you been recreant in that great crisis of our Nation, and of humanity’s long struggle, you and I would have parted long ere this! But I thank God, the record of this church for loyalty, patriotism and valor, at home and in the high places in the fields is without blot or stain.”

Stone died in San Francisco in 1892 at age 76. Matilda survived him and lived until 1904.

“As Stars Go Out With the Rising Sun”

Chaplain Sullivan Hardy Weston of the 7th New York State Militia delivered a sermon in the House of Representatives at the U.S. Capitol on Sunday, April 28, 1861. The date is noteworthy. The two weeks leading up to his appearance had been a whirlwind of head-spinning events: The bombardment of Fort Sumter, mobilization of troops, and the rush of Union regiments to protect Washington, D.C.

Against this backdrop, Weston, a 44-year-old Episcopal minister, preached a powerful sermon that echoed familiar themes of duty, country and God. “We are living in eventful times. Our National Capital is echoing with the tramp of armed men, and the glorious sunlight flashes back from thousands of glittering bayonets. ‘Grim-visaged war’ is upon us; and yesterday, on yon grassy field, a thousand ready right hands were raised to Heaven; a thousand willing voices rung out on the still air, pledged to sustain the Constitution of our common country.”

He continued, “My brethren, it cannot be denied, war is a tremendous evil. It has been the scourge of men since the primal, eldest curse, a brother’s hand was thicker than itself with brother’s blood. It appeals to the worst principles—arouses all the worst passions of the human heart. It throws Christianity back centuries. Language is powerless to paint its horrors.”

He accurately predicted future events when he noted, “Human arithmetic is impotent to cast the aggregate of the woes it entails. Blighted credit, ruined commerce, sacked cities, devastated fields, hospitals crowded with the maimed, battle-fields strewn with the slain, and lamentations of grief from the bereaved at home, who mourn their unreturning brave.”

Weston campaigned twice with the 7th during the Civil War and went on to serve in Trinity Church in New York City. His 1887 obituary honored him for his deeds over decades of work—including the sermon excerpted here.

Best Wishes for President Lincoln

On June 10, 1864, Rev. John Neil McLeod penned a letter to President Abraham Lincoln. In his role as clerk of North America’s Reformed Presbyterian ministers, it fell to McLeod to pass along top level church business. The letter’s timing, with Union forces stalled before Richmond and Atlanta and Lincoln’s reelection bid in doubt, may have influenced McLeod’s closing.

“Mr. President we wish you bodily health, mental tranquility, Divine support in the very responsible and arduous position to which you have been called, and the high pleasure of seeing our beloved country restored to peace on the basis of truth, righteousness and universal freedom, in due season. We only add, that we wish you personal salvation, that greatest of all blessings through Jesus Christ our Lord.”

McLeod, a 56-year-old first generation Scottish-American and the son of a minister, was also at something of a crossroads—militarily speaking. As chaplain of the 84th New York State Militia, he and his regiment had been activated for 30 days of federal service to counter Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Confederate invasion that culminated at Gettysburg, Pa. The 84th spent its time in the defenses of Baltimore.

A month after writing Lincoln, McLeod and the 84th were called up for a second and final time during the war—a 100-day stint to blunt rebel advances in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley. The regiment spent its time in Washington, D.C., and Winchester, Va.

McLeod returned to his clerical duties and died at age 67 in 1874 as pastor of the Twelfth Street Reformed Presbyterian Church in Brooklyn. He is buried in Green-Wood Cemetery.

ON SLAVERY

“Destroy Slavery for the Sake of the Union”

One of the earliest history books about the Civil War landed in bookstores in August 1862—while the outcome of the conflict was far from certain. A Narrative of the Campaign of the First Rhode Island Regiment in the Spring and Summer of 1861 described in detail the trials and tribulations of one of the Union’s first responders to the great peril that threatened to destroy the world’s experiment in government by the people. Augustus Woodbury, 35-year-old chaplain of the regiment, chronicled the organization, campaigns and men who lead the Rhode Islanders for a few months after the bombardment of Fort Sumter sparked all-out war.

A Harvard-educated Unitarian minister, Woodbury’s natural gifts for observation, reflection and communication are evident in this passage in the Battle of Bull Run chapter of the book: “The nation has learned at Manassas, that it is civilization and barbarism, freedom and slavery, republicanism and despotism, engaged in a life and death grapple—fighting for possession of a continent. The nation has learned that The Union stands for all that is best and noblest in the civilization of the nineteenth century—‘the best government that the world ever saw.’”

A month before distribution of the book and on the cusp of President Abraham Lincoln’s announcement of the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation, Woodbury struck a similar refrain in a July Fourth oration in Providence, R.I.: “At every fall of the ensign of secession, there must fall with it a link in the fetters of the slave. Our opponents have been willing to destroy the Union for the sake of slavery. They must not complain if we find it necessary to destroy slavery for the sake of the Union. The time is coming, when the preservation of the Republic will be the permanent triumph of liberty.”

Woodbury went on to write more books and contributed to secular and religious publications. A civic-minded man of action, he served in a variety of positions, including two terms in Rhode Island’s House of Representatives.

Rhode Islanders deeply mourned his death in 1895 at age 69.

“I Was Speaking in Defense of a Cause Which I Approved”

Along the eastern base of the Allegheny Mountains at Crab Bottom, the 44th Virginia Infantry settled in for the first winter of the war. The regiment’s chaplain, Richard McIlwaine, 27, recalled the severity of the weather in camp. “There was no house of worship and all our religious services during the week and on Sunday were conducted in the open air. I remember preaching on Sunday with a driving snow beating into my face, while the men were seated on stumps and logs in front of me, giving close attention.”

McIlwaine, a first generation Irish-American, grew up in Petersburg, Va. His father, Archibald, a prosperous flaxseed broker, owned slaves, including nine men, women and children in 1860. An ardent pro-slavery supporter, McIlwaine defended it as a Christian institution during his studies at Hampden-Sydney College, the University of Virginia, Richmond’s Union Theological Seminary, and Free Church College in Scotland. He once gave a speech on the subject before a student group he understood to hold an opposing view. “Being a slaveholder myself, having been born and reared in its environments and posted on the current views on both sides of the question, I felt qualified from personal knowledge and experience to comply, and so accepted the polite request.” He added, “I was speaking in defense of a cause which I approved, and as its representative, I did not shrink from telling them the plain facts of the case as I knew them to exist in Virginia.” He remembered many questions being asked and being thanked for his participation.

A few years later the war came. By this time, McIlwaine labored as a clergyman in the Amelia Court House area, not far from his alma mater of Hampden-Sydney. A staunch Unionist, he followed the lead of many Virginians and turned secessionist after the commonwealth withdrew from the Union. He promptly joined the Amelia Minute Men, which became Company H of the 44th. He started his enlistment as third lieutenant and volunteer chaplain, and several months later became the regiment’s chaplain. He posed for this portrait with his cousin, Frances S. McIlwaine, and her two daughters, Mary and Sarah.

McIlwaine served as chaplain during the Shenandoah Valley Campaign of 1862, but was forced to resign due to illness in August. He attributed his poor health in part to his preaching during the previous winter at Crab Bottom.

After the war, he returned to his ministry. In 1883, Rev. McIlwaine accepted the presidency of Hampden-Sydney and presided over a period of great expansion at the college. He resigned in 1904. Four years later in his autobiography, Memories of Three Score Years and Ten, McIlwaine reflected on his life and career, and waxed nostalgic about slave times. He died in 1913 at age 79. His wife, Lizzie, and five children survived him.

“Emancipate the Slave!”

When Rev. John Calvin Kimball joined the 8th Massachusetts Militia Infantry in November 1862, he brought his views on slavery with him. According to the history of his First Parish Unitarian Church in Beverly, Mass., Kimball was a virulent abolitionist who served up politically charged sermons from the pulpit. He shared his thoughts in an essay: “Almost three hundred years ago a couple vessels crossed the sea, one with slavery, the other with liberty, in its hold, and, planted on the same soil and influenced by the same environment, read on a thousand pages of American history written out in black and white and red, what they ripened to. Two hundred years later a descendent of that old Puritan stock, mobbed, ridiculed, despised, sent forth his ringing cry: Emancipate the slave!”

A graduate of Amherst College and Harvard Divinity School, Kimball became minister of First Parish Church in 1859. The war prompted him to take leave of his position and join the 8th for a 9-month enlistment in eastern North Carolina. This was the second of three federal activations of the regiment, and the only one in which Kimball participated. The first, a 90-day call in 1861, included the occupation of the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Md. The third call, for 100 days in mid-1864, involved garrison duty in Baltimore, Md.

According to First Parish history, the army asked Kimball to return in 1865, but the congregation refused to let him go. Kimball left five years later for a post in Hartford, Conn., where he befriended another Civil War veteran, Samuel Clemens. Both men lent their voices to protests against laboratory vivisection.

Kimball died in 1910 at age 77.

A Freedman’s Story

On June 18, 1864, Union Capt. Horace James inscribed the back of a carte de visite of a man dressed in tattered clothing. His words tell the tale of a slave’s escape to freedom.

“William Headley, a contraband from a plantation near Raleigh, N.C., arrived at Newberne, N.C., on the 20th May 1864, having been six weeks on the road, neither sleeping or eating in a house during the time. Two others left with him but were caught by the slaveholders’ Blood Hounds and either killed or taken back. He was weak and nearly famished when he arrived. His clothes were of many colors and qualities. His cloak consisted of an old cotton grain bag, slit open on one side and raveled which gives the impression of the side fringe. He appeared perfectly happy and satisfied upon reaching the Union lines and is now one of the best hands working on Ft. Chase, N.C.”

Fort Chase, one in a series of coastal fortifications constructed along the Neuse River opposite New Bern, mounted three 24-pounder cannon upon its completion. The fort was also close to one of several Freedman’s camps supervised by James, the Superintendent of Negro Affairs for the military Department of North Carolina.

The Massachusetts-born Yale graduate and Congregationalist minister spoke out against slavery before the war, while supporting gradual emancipation. In late 1861, he left the pulpit of the Old South Church in Worcester, Mass., to serve as chaplain of the 25th Massachusetts Infantry. The regiment participated in Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside’s successful North Carolina Expedition. Burnside placed James in charge of refugees—or contrabands—on Roanoke Island, which led to establishing a Freedman’s colony there and elsewhere.

James laid out his mission in a June 1863 open letter to encourage Americans to support the National Freedman’s Relief Association: “To colonize these freed people, not by deportation out of the country, but by giving them facilities for living in it; not by removing them north, where they are not wanted, and could not be happy; nor even by transporting them beyond the limits of their own State; but by giving them land, and implements wherewith to subdue and till it, thus stimulating their exertions by making them proprietors of the soil, and by directing their labor into such channels as promise to be remunerative and self-supporting.”

A year later, James, now a Quartermaster Department captain, encountered Headley, and recorded his story. Why James wrote on the back of this portrait is a mystery. Perhaps this is one of other such photos he inscribed. One truth is evident: In his role with Freedmen, James was uniquely positioned to hear similar stories from thousands of men, woman and children of color who made their way to the safety of the Union lines.

Headley’s fate is not known.

James remained in the army until 1866. The Roanoke Freedman’s Colony ended the following year after President Andrew Johnson withdrew federal support. James continued on his mission with the Freedman’s Bureau, and later as an editor of the Congregationalist newspaper and as a clergyman. He died in 1875 at age 57.

His name lives on in James City, N.C. Located across the Trent River from New Bern, it was first known as the Trent River Settlement, one of the camps established by James.

On Sugar Planters and Men in the Union Ranks

Chaplain George Hughes Hepworth arrived in Louisiana with the rest of the 47th Massachusetts Infantry on the last day of 1862. Though in uniform only a month, he later wrote, “I had already begun to feel that my chaplaincy tended to confine rather than give ample scope to my desire for work.”

Having met the overall commander of Union forces in the region, Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks, Hepworth requested and received an assignment as first lieutenant in the 4th Louisiana Native Guards. Banks placed Hepworth on his staff with orders to investigate and report on labor in Louisiana.

Hepworth, 29, brought his Harvard education, Unitarian faith and ardent abolitionism to bear as he traveled Louisiana during the immediate aftermath of the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation. Over the remaining seven months of his enlistment, he chronicled plantation culture in his book, The Whip, Hoe, and Sword; The Gulf-Department in ’63. He summarized his experience in the introduction: “If I talk a great deal of slavery, it is because I have seen a great deal of it. If I say no good thing of it, it is because I found no good thing in it. I learned to pity the slaveholder and the slave, and to thank God and the genius of the age for the Proclamation.”

In his book, published before the end of 1863, Hepworth directed his harshest criticism to those who enslaved people. “You may talk with a planter upon almost any subject, and you will find him affable and gentlemanly. He will scorn to misrepresent an event, and will speak with commendable charity of his neighbors. The moment, however, the conversation edges towards slavery, his demeanor changes. He either grows reticent, and refuses to say a word; or else becomes angry, and openly insults you on the spot.”

He continued, “There is no such thing as a calm discussion of the subject with him: he seems to think that any assertion, true or false, is fair. If he can adduce facts, he will pile them up; until, at last, you begin to think the best thing the Almighty can do is to get up an extra generation of negroes for the use of the Southern sugar-planter. If the facts are not readily handled, he hammers away at the Old Testament; quoting verse after verse, trying to prove that the venerable book has no higher mission than to afford favorite texts for the slaveholder. … If you suggest that the thralldom of a race impedes civilization, and is an inhumanity done to the enslaved, he harangues you on the value of the institution as a missionary society,” elevating “a whole people from the depths of barbarity.”

By contrast, Hepworth reserved the highest praise for the Union rank and file after a tour of camps in Baltimore and Washington, D.C., about six months before he joined the army. “I conversed with many of the privates,” he explained, “and I found everywhere a degree of enthusiasm which surprised me.” He continued, “Their purpose is not conquest. They know they are fighting for more than twelve dollars a month—it is for principle.”

Hepworth went on to serve as a pastor in New York City, and later became a Trinitarian. He left the ministry in 1885 to work as a journalist for the New York Herald, and authored numerous books. He died in 1902.

West Virginia Leader

In October 1861, Gov. Francis H. Pierpont of the Restored Government of Virginia turned to an old college classmate, Gordon Battelle, to inspect military camps. He made an excellent choice. An Ohio-born educator and minister in the Methodist Episcopal Church, Battelle had service and patriotism in his blood. His grandfather, Ebenezer, had volunteered at Lexington in 1775 and served throughout the Revolution.

Battelle, who met Pierpont at Allegheny College at Meadville, Pa., settled in western Virginia after graduation and taught school in Clarksburg. As threats of civil war loomed on the near horizon, Battelle moved to Wheeling to accept a leadership position with the church. Outspoken against secession and slavery, he was elected a delegate to the constitutional convention for the new state of West Virginia. He proposed language for the gradual emancipation of slaves, which was not adopted.

About this time, Pierpont sent Battelle on a mission to inspect and report on camp conditions. Before the end of 1861, Battelle received a new assignment as chaplain of the 1st West Virginia Infantry. His service ended prematurely the following year when he contracted typhoid fever and succumbed to its effects at a Washington, D.C., hospital in August 1862. He was 47.

Battelle’s remains were carried to his native Ohio and buried in Newport Township. In 1913, a memorial to honor the sons of Newport who served in the Civil War was dedicated. The monument is topped with a statue of Battelle, a teacher, patriot, and leader in the formation of the state of West Virginia.

—Richard A. Wolfe.

THE UNIFORM

The “Chaplain of Hood’s Texas Brigade”

In the early autumn of 1861, Chaplain Nicholas A. Davis of the 4th Texas Infantry walked into a tailor’s shop on Main Street in downtown Richmond, Va. Flush with cash from his first pay since he arrived in town, the 41-year-old Presbyterian minister commissioned a uniform. He cut a striking figure in his new clothes.

So impressed was a fellow minister by Davis’ appearance, he shared his observations in a letter to the editor of the Richmond Enquirer. “I observed a Chaplain,” stated the clergyman, “in uniform on yesterday, which uniform I admired above anything I have yet seen. A suit of black clothing strait breasted, with one row of brass buttons, and simple pointed cuff with small olive branch about six inches long, running up the sleeve.”

Chaplain Davis wore his uniform for three ambrotypes taken in Richmond, including this one, for family in his native North Alabama and his adopted state of Texas. The son of a slave owner and Southern Rights Democrat who had served as an Alabama State legislator, Chaplain Davis had studied theology with a local minister and served communities in the region. He and his wife, Nancy, moved to Texas with their two daughters in 1852 and settled in Bastrop County outside Austin. Davis, like his father, owned slaves, including 13 people of color in 1860.

By the time Davis left Texas for Virginia in the summer of 1861, his wife and a son born in the Lone Star State had died.

In Virginia, Davis’ commanding presence, powerful sermons and organization of the Texas Hospital to consolidate sick and wounded men, left a positive impression with many soldiers. They included the colonel of the 4th, John Bell Hood, who went on to rank as a lieutenant general. Davis became known as “Chaplain of Hood’s Texas Brigade,” though he was never detached from the 4th.

During the early part of the war, Davis wrote numerous letters, editorials and other writings. In one essay about the enemy he asked, “By which name shall we call them?” He debated whether the term Abolitionist, Unionist, Federal or Yankee was most descriptive. He eventually settled on Yankee, which he defined as New Englanders and “all their ten thousand schemes of deception and fraud … their every act of lying and stealing, from the days of Washington till the present hour, in all their political, legislative, executive, commercial, civil, moral, literary, sacred, profane, theological and diabolical history.” He added, “The Yankee country has given birth to Socialism, Mormonism, Millerism, Spiritualism and Abolitionism, with every other Devilism which has caused the nation of Unionism. And, as there is one word that will express all these and a hundred more isms, I prefer to use that word, and thereby say all that can be said on this subject—the term is YANKEEISM. And we will call them Yankees.”

Davis survived the war and returned to Texas, where he remarried and fathered four children. He remained active in his ministry and in business before his death in 1894 at age 70. He left behind an 1863 book, Campaign from Texas to Maryland, with the Battle of Fredericksburg, which documented his war experiences. Much of the information here is based on an expanded 2018 edition edited by Dr. Donald E. Everett.

“Too Noble for Gilt and Tinsel”

Following his appointment as chaplain of the 2nd Massachusetts Infantry in the spring of 1861, Rev. Alonzo Hall Quint took on another task—correspondent. The editors of the Congregationalist, a weekly newspaper of his faith, invited him to share his experience. They could not have made a better choice. Born in New Hampshire and educated at Dartmouth College and Andover Theological Seminary, his collected writings, with additional commentary, were published in 1864 as The Potomac and the Rapidan.

In a December 1861 submission, Quint commented on new army regulations that required chaplains to wear an unadorned frock coat sans shoulder straps. He also discussed the relationship of a chaplain to the army, referencing Lt. Gen. Winfield Scott and a former general, President Andrew Jackson.

“Let me say a word on the recent orders as to chaplains, concerning dress, &c. It is said, in some papers, that many chaplains are dissatisfied. This may be true at Washington, but it is not so in this division. It is, perhaps, pleasing to me that the simple dress now prescribed is the precise one stated as proper by our commander, when I was leaving home, and which, of course, I procured. The shoulder-straps, gilt buttons, and swords, on some chaplains, have always excited the ridicule of army officers.”

Quint continued, “The less a chaplain assumes to be a military man, the better. His influence is that of a Christian minister. Men expect that, but they do not expect a mere preaching officer. As to rank, due respect, &c, a chaplain needs no military rank, nor exacted salutations. As General Scott informed a committee, a chaplain will secure that position his qualities entitle him to occupy; that is, when officers are gentlemen. Some regiments—many—have officers not what they should be; and there the best of chaplains find trouble. But the reverse is sometimes true. In this division, we are glad of the new regulation. We believe that a chaplain’s position is too noble for him to need gilt and tinsel. General Jackson once told a minister applying for office, ‘You have a higher office than is in my power to bestow.’ So has a chaplain; but it is not a military office; it is that of friend, adviser, and helper, to both officer and private alike. With such material as ours a chaplain feels no lack of rank or show.”

Chaplain Quint went on to author The Record of the Second Massachusetts Infantry, 1861-65, and serve several yearlong stints as chaplain-in-chief of the Grand Army of the Republic. He enjoyed a long association with the Congregationalist church in New Bedford, Mass., and died at age 68 in 1896.

IN CAMP

Pensacola’s Chaplain

After his arrival at Pensacola, Fla., during the summer of 1863, Union Navy Chaplain Robert Givin learned of an abandoned chapel. An enterprising ensign pitched in to renovate it for religious services. Givin then spent more than two years there tending to the spiritual needs of Bluejackets, and ministering to crews passing through the harbor and patients in the Navy Yard hospital.

A Methodist minister born in Philadelphia, he began his life’s work in New Jersey. In 1855, he received an appointment as a Navy chaplain, later telling a friend that he did so to be able to visit various missionary centers around the world. His travels took him as far as China.

When the war began, Givin joined the crew of the frigate Roanoke for duty in the North Atlantic Blockade Squadron. In 1863, he joined the Potomac, the flagship at Pensacola. In addition to conducting services, he distributed religious materials and schoolbooks. In an early 1865 report, Given noted, “Both afloat and ashore I find good and attentive congregations and have good reason to believe that my labors have not been altogether unprofitable, though they have not been so successful as desired.”

Givin remained in the Navy after the end of hostilities. In 1872, he became one of the first four chaplains in Navy history to attain the relative rank of captain. He eventually retired and died in 1895 at about age 76. He is buried in West Laurel Hill Cemetery at Bela Cywyd, a suburb of Philadelphia.

Henry Wilson’s Chaplain

In Virginia during the early months of 1864, a chapel graced the winter camp of the 22nd Massachusetts Infantry. Built of hand-hewn logs and covered by a canvas roof supplied by the U.S. Christian Commission, the building served many purposes—Masonic lodge, debate society, dance hall, and a place for young men to improve their intellectual and moral well-being.

The man who made this a spiritual home for the Bay State boys, Chaplain Charles Mellen Tyler, had joined the regiment in January 1864. A Maine-born and Yale educated minister, Rev. Tyler presided over a Congregationalist church in Natick, Mass., when the war began. One of the members of his flock, influential U.S. Senator and future Vice President Henry Wilson, was a close friend. When Congress recessed during the summer of 1861, Wilson returned to his home state and recruited the 22nd. Tyler, meanwhile, served as a member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives from 1861-1862.

In late 1863, Tyler joined Wilson’s regiment and arrived in camp in mid-January 1864. His new comrades erected the log and canvas chapel soon afterwards. Here Tyler delivered a number of popular sermons. He gave his last sermon in the chapel on April 24, 1864. Early the next month he accompanied the men into the Overland Campaign, and served with them through the battles of The Wilderness and Spotsylvania, and operations against Petersburg.

Tyler resigned in July 1864, and returned to Massachusetts. In 1872, he joined the faculty of Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y., as a professor of history and philosophy, and of religion and of Christian ethics. He retired in 1903. Upon his death in 1918 at age 86, Cornell faculty remembered their late colleague as a unifying spirit.

“No one did more to make us realize that, as members of the University, in spite of all differences in our methods of approaching the truth, we are spiritually one body, and that our interests are not confined to the material and to the temporal.”

It is a role he also played during his six months in uniform during the Civil War.

Naval Academy Chaplain

The U.S. Naval Academy swung into full operation at its temporary location in Newport, R.I., during the 1862-1863 academic year. Far from the rebel threat that prompted the school’s relocation from Annapolis, Md., four classes of cadets, 400 in all, learned the art of war. The staff of 34 instructors included William Augustus Hitchcock, the Academy’s chaplain, who performed double duty as assistant professor of ethics and English studies.

Chaplain Hitchcock joined the Academy from private life. Born in New Haven, Conn., and educated at Trinity College and Berkeley Divinity School, he became rector of St. John’s Episcopal Church in Portsmouth, N.H., in 1858.

Three years later he resigned to become a Navy chaplain, and joined the Academy as its spiritual head. Especially memorable was his service during the summer cruise of 1863. Assigned to the practice sloop Macedonian, the cadets gained real-world experience in New York’s Long Island Sound.

Chaplain Hitchcock’s stint in Newport ended in early 1864 when he received orders to join the 360-man crew of the screw frigate Niagara. Assigned to the European Squadron, the vessel patrolled European waters in search of Confederate vessels.

Hitchcock went on to serve aboard the training ship Sabine and resigned in 1867. He returned to the ministry at churches in Pennsylvania and New York, and earned a Doctor of Divinity degree. He declined the Bishopric of western Pennsylvania in favor of active work with congregants.

While minister of the Church of the Ascension in Buffalo in 1895, Hitchcock suffered head injuries after he attempted to exit a moving trolley car. One source attributed his death three years later at age 64 to the accident. His wife and four children survived him.

Camp Meetings With Chaplain Little

Chaplain Joseph Little posed for this portrait with the tools of his trade—a rocking melodeon, hymnbook and a large-print poster for sing-a-longs. The musket propped up against the studio wall behind him may be a symbol of the young men of the 5th West Virginia Infantry to whom he ministered.

This carte de visite was likely used as a reference by the illustrator who created a unique piece of art distributed by Little to soldiers under his care. The caption reads, “Our chaplain gives us each a copy of this Engraving, to show our friends the way we sing and hold meetings in camp. He desires us to tell them to pray for us and him, that we may prove faithful to our country and our God, and not be found wanting in any day of temptation and trial.”

A Presbyterian minister born in Licking County, Ohio, Little joined the 5th in October 1862 with the endorsement of the officers of the regiment, who petitioned the governor of loyal Virginia to commission him. “We have entire confidence in his ability, patriotism and Christianity. He is also a social, companionable gentleman and will exert a good influence over the soldiery.”

Little served the spiritual needs of his comrades until captured near Winchester, Va., on Sept. 27, 1864. The Confederates recognized Little as a non-combatant, and sent him back to Union lines with an unconditional parole less than two weeks later. The chaplain returned to his regiment and remained with his comrades until July 1865.

After the war, Little resumed his ministry. He died in 1882 at Granville, Ohio, and is buried in Maple Grove Cemetery.

—Richard A. Wolfe

Bucktail Chaplain

On the first Sabbath of June 1863, the new chaplain of the 149th Pennsylvania Infantry preached his inaugural sermon. Health issues had delayed Rev. James Frederick Calkins, a Presbyterian minister in Wellsboro, Pa. According to an historian, Calkins’ delay was worth the wait. A New York native with degrees from Union College and Auburn Theological Seminary, he had established the church in Wellsboro soon after graduation in 1844. “He not only ministered to the spiritual wants of the soldiers, but their physical needs, and in the day of battle helped to care for the wounded and the dying with a devotion and bravery that won their lasting regard.”

The first opportunity Chaplain Calkins had to serve on a battlefield occurred just a few weeks after his arrival—at Gettysburg. The 149th, also known as the 2nd Bucktail Regiment, fought hard and suffered heavy losses along Seminary Ridge during the first day’s engagement. The Bucktails went on to fight in the Overland Campaign in 1864 and during operations around Petersburg, Va. In early 1865, the regiment received orders to guard the Confederate prison camp at Elmira, N.Y., and served in this capacity until it mustered out in June 1865. During the regiment’s stay, Chaplain Calkins posed for this portrait.

Calkins returned to his ministry in Wellsboro and other Presbyterians in Tioga County until his retirement in 1879. A regular at regimental reunions, he also welcomed a number of Bucktail veterans who visited to pay their respects. Calkins passed in 1893 at about age 77.

Navy Scholar

Two men from the wealthy Hale family of Philadelphia, Pa., participated in the war. Attorney Reuben C. Hale served as Quartermaster General of the state and played a key role in the development of the Reserve Corps. He died on July 2, 1863, as battle raged in Gettysburg.

Navy ScholarThe other, his son, Rev. Charles Hale, joined the Navy. In March 1863, he donned the blue uniform and the shoulder straps of a chaplain.

On paper, the Navy fell five chaplains short of its authorized total of 24. As Hale and others joined the force, Assistant Secretary of the Navy Gustavus V. Fox wondered what to do with them, and considered his options. Hale subsequently landed on the staff of the Naval Academy’s temporary location in Newport, R.I.

Hale thrived at the Academy as a math instructor. Prior to his ordination as a priest in 1861, he had earned undergraduate and master’s degrees at the University of Pennsylvania, where he had displayed talent as a linguist and translator. In 1859, while an undergraduate, he gained national attention after he and two fellow students translated a section of the Rosetta Stone from a plaster cast of the famed relic discovered in Egypt by a French soldier during Napoleon’s Egypt campaign 60 years earlier.

Hale’s stint at the Academy ended in February 1865 when was ordered to report to Rear Adm. Louis M. Goldsborough. He spent the next six years with the European Squadron, where world travel fueled his passion for language. Following his 1871 resignation, Hale rose to prominence as one of the country’s foremost linguists. He later also advanced to great heights in the church hierarchy as Bishop of Cairo in Illinois.

On Christmas Day 1900, Hale died of heart disease at age 63. He outlived his wife, Anna, whom he had married in 1872. The couple had no children. His remains were brought home to Philadelphia and buried with honors.

Shock in The Wilderness

On May 6, 1864, the 57th Massachusetts Infantry experienced the full shock of first battle in one of the war’s most brutal engagements—The Wilderness. Organized five months earlier, the regiment’s number included Chaplain Alfred Henry Dashiell, Jr. A Maryland native and son and grandson of ministers, he had most recently led a Congregational Church in Stockbridge, Mass.

In The Wilderness, Dashiell witnessed the rout of his comrades. “The men streamed by in panic, some of them breaking their guns to render them useless in the hands of the rebels. Nothing could stop them until they came to the cross roads where a piece of artillery was planted, when they rallied behind it.”

At this point, the colonel of the 100th Pennsylvania Infantry, Daniel Leasure, happened on the scene and placed the men in line. Dashiell reported, “Before long the rebel yell was heard and the colonel on the gun cried, ‘Advance, first line!’ When a volley succeeding the discharge of the artillery made the rebels ‘skedaddle’ in turn.” Dashiell advanced with the musicians to care for the wounded and carry off as many as they could to safety. Among those who the chaplain encountered was his colonel, William F. Bartlett, with blood streaming from his forehead.

Dashiell remained with the 57th through the rest of the war, and by all accounts was beloved by the men he ministered. In 1867, he moved to Lakewood, N.J., to become the founder and minister of the Presbyterian Church. Upon his death in 1908 at age 84, he left behind his second wife (his first had died before the Civil War) and three children.

Old Rosey’s Chaplain

There came a moment during the first day’s fight at Stones River when Union infantry formed a line of battle amidst a shower of shot and shell. As the officers and men moved into a precarious position, a priest on horseback approached. He stood high in the saddle and spoke in a powerful voice, “Men prepare yourselves. I will give you the general absolution.”

The soldiers, all Catholic, listened as the priest recited the Confiteor, a prayer of confession. Then, he asked the men to perform an Act of Contrition. The soldiers removed their caps and prayed on bended knees as he absolved them of their sins to the sound of musket and cannon. The sacred act complete, the men advanced into the maelstrom as the priest rode to the rear of the batteries to await the wounded and dying that were sure to follow.

The priest, Father Jeremiah F. Trecy, had come to America in the 1830s from Ireland with his parents. Though his family made a home in Philadelphia and Lancaster, Pa., Trecy left to follow the call of the priesthood. His travels took him to the Irish Catholic settlement in Garryowen, Iowa, then further west into Nebraska Territory, where he brought the faith to frontier forts and Native American nations.

In 1860, Trecy requested and received permission from the Church to go to the South for health reasons. His move coincided with the presidential election of Abraham Lincoln and the dissolution of the Union. By this time Trecy had landed in Huntsville, Ala., where he began to establish a church. The war interrupted his pursuits. During the early part of hostilities, he tended to the spiritual needs of Confederate soldiers in camp and area hospitals, and after Huntsville was occupied provided the same services to Union troops. His lack of bias and ability to keep his faith above the fray roused suspicion on both sides of the conflict. On the battlefields of Iuka and Corinth, Miss., he tended to wounded in blue and gray.

Trecy eventually found a wartime home at the headquarters of Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans. A devout Catholic, “Old Rosey” and Trecy enjoyed a special bond. According to an 1863 biographical sketch, Trecy was “the constant spiritual companion of the General, and whose fidelity to his Chief was second only to his devotion to the faith he preached.”

Perhaps the best illustration of this connection occurred at Stones River, where Father Trecy blessed Union soldiers before they marched into battle.

A few days after the fighting ended, on Jan. 4, 1863, Trecy conducted Mass in a crude log cabin on the battlefield still strewn with horse carcasses and occupied by burial parties. Trecy’s service and remarks brought many officers of the high command to tears.

Father Trecy and the general eventually parted ways. Trecy returned to Huntsville to continue the church he had started, and was buried there after his death in 1888 at about age 65.

“Doer of the Word”

On many a grueling march through the wilds of North Carolina in 1863, Chaplain Charles Andrew Snow of the 3rd Massachusetts Infantry gave his horse to a weary foot soldier. By all accounts, the self-sacrificing minister of the Baptist faith enjoyed a reputation as a man of “divine cheer” and a “doer of the word.”

Born in Providence, R.I., Snow grew up in poverty in a family of 18 children. Dropping out of school to work, friends talked him into returning six months later. He did, and went on to Brown University and Newton Seminary in Massachusetts. Ordained in 1858, he became pastor of the Second Baptist Church in Fall River, Mass.

In 1862, he helped organize a nine months’ regiment that mustered in as the 3rd. The regiment spent the majority of its enlistment in North Carolina. As chaplain, “he won high respect and admiration by his consistent conduct and his spirit of self-denial,” stated one writer.

Years later, when the veterans of the 3rd determined to produce a history of their service, Rev. Snow was their choice to write it. He made it as far as profiling Company A before he died in 1903. He was 74. His wife and six children survived him.

At Abingdon House

On May 24, 1861, the 3rd New Jersey Militia Infantry marched from Washington, D.C., into Virginia in support of Union forces ordered to capture Alexandria. After the Jerseymen crossed the Potomac, they came upon stately Abingdon House. Located only a few miles from Gen. Robert E. Lee’s manor, Abingdon had reportedly been looted by men from another New Jersey regiment.

The 3rd made Abingdon its overnight quarters despite the mess. The officers were assigned rooms. Chaplain John Livingston Janeway and two other officers occupied one on the second floor. Janeway, a Pennsylvania-born Presbyterian minister educated at Rutgers, entered the room and found drawings, paints, photos, ribbons and lace strewn about the place. The officers deduced the occupant had been a lady of artistic talent, and began to clean up. But the task proved hopeless, so they piled the mess into a corner and went to sleep.

Janeway and his comrades mustered out of the army in late July at the end of their 3-month enlistment—a day after the Battle of Bull Run, which they missed.

Janeway went on to become chaplain of the 30th New Jersey Infantry. The regiment was in an exposed position at Chancellorsville but did not see combat and mustered out soon afterwards.

Janeway returned to the church and lived until age 91, dying in 1906.

Six Weeks a Chaplain

Rev. Henry D. Moore, the son of a Philadelphia cotton merchant, served as a Congregationalist clergyman in Portland, Maine, when the war began. In March 1862, he received a commission as chaplain of the 13th Maine Infantry.

His tenure in the regiment lasted approximately six weeks.

On February 28, Chaplain Moore and his comrades traveled aboard the transport Mississippi to the South. The transport’s passengers included Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler, his wife and staff. The Mississippi, packed with about 1,500 souls, encountered severe weather off the coast of North Carolina, and eventually ran hard aground. The gunboat Mount Vernon, part of the blockade squadron, transferred troops to lighten the load, and then pulled the vessel off the shoal upon which it had become stranded with a hawser.

The next morning, a survey of the damage resulted in a decision to divert to Union-occupied Port Royal, S.C., for repairs. That same day, Chaplain Moore tendered his resignation. How he came to resign revolves around events connected to his transfer from the Mississippi to the Mount Vernon—and a nasty run-in with Butler.

In Butler’s 1892 autobiography, the general claimed that Moore offered to accompany Mrs. Butler off the grounded Mississippi. Although Butler declined, Moore persisted. “General, I prefer to go,” he reportedly told Butler, who replied, “The devil you do! Look here, chaplain, the government has trusted the bodies of fifteen hundred of its soldiers to my care, and their souls to my care, and if your prayers are going to be of any use it will be about now, as it looks to me. You cannot go, sir.” Butler then left to deal with other matters.

Butler remained on the Mississippi while his wife took refuge aboard the Mount Vernon. The next morning, after the survey, a crew rowed him over in a small boat to fetch his wife. He explained what happened next. “As I approached the quarter deck, whom should I see on her deck but my chaplain of the long flowing curls and Byronic collar.” The portly Butler hurried aboard the Mount Vernon, and, after a brief, pointed exchange, ordered Moore to write his resignation. Butler reviewed the document and told Moore his discharge would be mailed to his home. Then he turned to the ship’s captain and said, “You can keep this fellow or throw him overboard, just as you choose; I wash my hands of him. I haven’t any more use for him, although he may be the Jonah that went overboard and saved the ship.”

The 1896 regimental history of the 13th supported Butler. “All who had been transferred to the Mount Vernon were returned to the Mississippi, except one staff officer of the 13th; who, although like a guide-post pointing the way to heaven, had no personal desire to go there by water! He, therefore, remained on the uninjured vessel and sent in his resignation, which was promptly accepted by Gen. Butler.”

The colonel of the 13th, Neal Dow, a temperance activist and politician, noted in his 1898 reminiscences that he had ordered Chaplain Moore to safety aboard the Mount Vernon, but did not elaborate.

Moore never returned to the military and left Maine. By 1865, he led a congregation in Pittsburgh, Pa., and eventually landed in Cincinnati, Ohio, where he edited the Masonic Review. A controversial article in support of Cerneauism, a rival form of Scottish Rite Masonry, led to his ouster and indefinite suspension in 1885. He died in 1901 and is buried in Cincinnati. His wife and a daughter survived him.

Spirit Lake

On June 18, 1864, a Union officer wrote to his mother about life in the Columbus, Ky., camp where he and his comrades had recently settled. In his letter, 1st Lt. Andrew L. Hunt of the 134th Illinois Infantry mentioned the regiment’s 27-year-old Methodist minister, Amos King Tullis. “I like our Chaplain very much.” Hunt added, “He is a man of not very great mental culture—a country minister and has bad grammar. Still, I like him.” He further noted, “He is quite pleasant and has been in the army before.” The lieutenant referred to Tullis’ 3-month stint in late 1862 as chaplain of the 102nd Illinois Infantry.

Tullis had had another experience, paramilitary in nature, which he did not talk about. In early 1857, he happened to be in Webster City, Iowa, when news arrived that white settlers had been massacred by Sioux Indians about 125 miles away in Spirit Lake. Tullis joined a band of men to avenge the dead. He and his comrades endured brutal late winter weather on what became a recovery operation to locate and bury the bodies of the slain. By all accounts, the return trip to Webster City in cold and snow exposed the men to extreme conditions. Some historians connect what became known as the Spirit Lake Massacre to the violence between Native Americans and settlers a few years later in Minnesota.

How the Spirit Lake experienced shaped young Tullis is not entirely clear, though his silence on the subject is suggestive. Also of note: Less than three years later, in 1860, he joined the Central Illinois Conference of Methodists.

His war service began with the 102nd and ended abruptly with his resignation three months into his commission. Tullis told 1st Lt. Hunt that the regiment “was the most immoral one in the whole United States as far as he could find out and he made great efforts.”

Tullis had the opposite experience in the 134th, where his sermons were well received. The regiment mustered out of the army at the end of its 100-day enlistment in October 1864.

The reverend returned to the Central Illinois Conference and ministered for decades. One Sunday in September 1920, he attended church in Benton Harbor, Mich. During the service, he bowed his head in prayer, and passed away. His wife and eight children survived him.

Tullis never told his children about his participation in the Spirit Lake expedition. They found out only after the State of Iowa pensioned him and other survivors.

Temple of Liberty

Chicago Mayor John B. Rice stood on the steps of the city’s Court House on July 14, 1865, and looked out into the square and a sea of faces. Throngs had gathered to welcome home the officers and men of the 64th Illinois Infantry after more than three years in uniform. The mayor delivered a speech that honored their service and sacrifice to the Union. He ended with a new call to action: “Another duty, when you return to the peaceful walks of life will be to cultivate the great Christian principle of brotherly love, to forgive and forget, and let every man build up a temple of liberty within his own breast, whose cornerstone shall be conciliation and mercy.”

One man in particular must have taken the mayor’s challenge to heart—the regiment’s chaplain, Alfonso D. Wyckoff. An Ohio native who moved to Illinois as a boy, he had lived an exceptionally active life for a man of 35: Apprentice to a cabinetmaker; Ship’s carpenter on a vessel blown of course to Hawaii; Chasing gold in California; Student at Wheaton College; Ordination in the Congregationalist Church in 1863.

In April 1864, a year after he became a minister, Wyckoff joined the veteran staff of the 64th, which had originally formed as Yates’ Sharp Shooters, a battalion named for Illinois Gov. Richard Yates. Wyckoff served during the Atlanta Campaign, the March to the Sea and the Carolinas Campaign.

After he mustered out, Wyckoff returned to the ministry until 1872, when failing eyesight compelled him to leave the church. He eventually went into the drug store business with a brother and settled in York, Neb. He served as the city’s mayor from 1888-1889, and oversaw the completion of major civic projects.

Wyckoff lived until 1915, dying at age 84 in Escondido, Calif., where he had relocated after his retirement. He outlived his first wife, Lovina, who had died in 1890. Three of their children and his second wife, Sarah, survived him.

General Butler’s Campaign on the Hudson

Chaplain Henry Norman Hudson spewed a torrent of sarcasm at Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler, declaring, “You, Sir, a just man! And comprehending no higher force in human affairs than terror and torture! As for your sense or idea of justice, one half of it, I think, must have been in high glee when you juggled and spirited off—whither, O! whither?—that $50,000 of gold in New-Orleans. For the other half, why, when a Shylock or a General Butler talks of justice he means revenge.”

How Hudson, a minister in good standing with the Episcopal Church and chaplain of the respected 1st New York Engineers, came to upbraid Butler is rooted in a personal tragedy, freedom of expression and miscommunication.

In May 1864, Hudson received orders signed by Maj. Gen. Quincy A. Gillmore to travel from his post with the Army of the James in Virginia to New York City to supervise the printing of official materials. Gillmore explained that specific instructions would be sent to him after he arrived in New York. As he prepared to depart, Hudson learned that his 7-year-old son, William, had fallen gravely ill. Gillmore modified the orders to allow Hudson to visit his family in Massachusetts. His son died and his broken-hearted wife, Abby, fell sick with profound grief. Hudson himself had been suffering from digestive issues and was not especially well.

Meanwhile in Virginia, Gillmore openly feuded with Butler after the failed Battle of Drewry’s Bluff. Gillmore asked for and was granted reassignment to another command. He never sent the instructions to New York, leaving Hudson unsure of his next move. To add to the confusion, his regiment of engineers were scattered on various detached duties and without a central point of concentration. Discouraged, Hudson traveled to New York City and handed his resignation letter to his colonel, Edward W. Serrell, who happened to be in town on business.\

None of this activity on its face would have incurred the wrath of Butler. But the wily political general knew a secret. Hudson had written a scathing letter about Butler’s generalship at Drewry’s Bluff and sent it to a friend, journalist Parke Godwin. Back in 1862, Hudson had made an arrangement with Godwin to send him periodic commentaries on army life to be printed in the New York Evening Post under the pseudonym “Loyalty.” Hudson’s Drury’s Bluff comments did not fall into the scope of this arrangement, so were printed anonymously in the Evening Post.

Butler read the commentary and connected the dots to Hudson. In mid-September he sent Hudson a terse summons to report to headquarters. A showdown ended with Hudson’s arrest and an almost 2-month confinement in Provost Guard prison. The chaplain’s 1865 book, General Butler’s Campaign on the Hudson, detailed the events. Butler told his side of the story in his 1892 autobiography.

Hudson left the army with a dishonorable discharge that was reversed after an intervention by Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, who had little respect for Butler. Hudson returned to Massachusetts, where he died in 1886 at age 71. His wife and a son survived him.

Bracing for the Old Snapping Turtle

Nine days after the Battle of Gettysburg, the Union and Confederate armies poised for renewed fighting on the Maryland side of the Potomac River near Falling Waters. At one point that Sunday, July 12, the federal commander, Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, and his staff arrived near the position of the 118th Pennsylvania Infantry. Three companies from the regiment soon received orders to move in support of the picket line.

Battle appeared imminent. The Pennsylvanian’s chaplain, William J. O’Neill, was unhappy about fighting on the Sabbath. A son of Ireland and the younger brother of the regiment’s major, Henry O’Neill, he had labored as a Methodist minister in Philadelphia prior to his enlistment.

O’Neill strode solemnly with hat in hand to Meade and boldly asked the general to postpone an attack until the next day. The historian of the 118th spoke for many eyewitnesses who braced for Meade’s reaction, for the general’s irascible nature had earned him the nickname “Old Snapping Turtle.”

The regimental historian reported that Meade was unexpectedly gracious and told O’Neill he was like a man who had a contract to build a box. Four sides and the bottom were complete. Now, it was time to finish the job.

O’Neill bristled. “I solemnly protest, and will show you that the Almighty will not permit you to desecrate his sacred day with this exhibition of man’s inhumanity to man.” He brought Meade’s attention to storm clouds overhead, which seemed to respond to the chaplain’s call when they erupted in a violent thunderstorm.

Meade ultimately delayed and the Confederates slipped across the Potomac to Virginia soil.

Chaplain O’Neill continued to serve the 118th through the war’s end and ministered to Methodists until his death in 1887 at about age 55. News of his passing made it across the Atlantic to O’Neill’s birthplace in Lisburn, Ireland, where he was mourned.

Campaigning with the “Old Sixth”

One Friday in September 1862, Chaplain John Wesley Hanson arrived in the Suffolk, Va., camp of his regiment, the 6th Massachusetts Militia Infantry. The regiment had recently been activated for federal service for a 9-month enlistment. A Boston-born Universalist minister, Hanson conducted his first Sabbath service two days later.

Hanson did not record the occasion, but did leave behind this general description of Sundays in his Historical Sketch of the Old Sixth Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteers: “The men generally, though always voluntarily, attended service. Several hundred usually formed a square in front of the head quarters, the chaplain standing on a box, behind a pile of drums, and discoursing briefly, to an attentive audience, with singing of the first order.”

He also noted a spirit of cooperation between regimental chaplains at Suffolk. Representing six Christian denominations, they gathered weekly to discuss the needs of their regiments. “Their union of action and spirit gave a very good example to those of their profession out of the army,” he observed.

Hanson’s Virginia stint was the first of two campaigns in which he participated. The second, a 100-day period in 1864, was spent in Washington, D.C., and Fort Delaware, Del. Hanson did not participate in the regiment’s first federal activation in 1861, a 90-day call best remembered for the pro-secession riot in Baltimore, Md., also known as the Pratt Street Riot.

Between his two campaigns in 1862-1863 and 1864, Chaplain Hanson conducted a unique East Coast tour under the auspices of the Soldiers’ Mission, an aid group organized by the Massachusetts Convention of Universalists. Hanson visited every Massachusetts regiment stationed from Washington, D.C., to Florida from January to April 1864.

Hanson’s military experience ended with the war. He went on to become a prolific writer on Universalism, including an 1885 revision of the New Testament for his faith. Hanson lived until age 78, dying in 1901.

IN HOSPITALS

“Rations for the Intellect, Food for the Mind”

Soldier-patients at Campbell General Hospital in Washington, D.C., enjoyed a steady diet of popular lecturers, a well-stocked library and theatrical performances. The person responsible for all of it, Chaplain Noah Murray Gaylord, had joined the hospital staff in early 1863 after 20 months as chaplain of the 13th Massachusetts Infantry. According to a newspaper report, Gaylord was “aware that sick and convalescing soldiers need mental hygiene as well as the surgeon’s remedies,” and was “constantly at work in providing rations for the intellect, food for the mind, as an auxiliary to the medical treatment of the patients.”

Gaylord, an Ohio native, responded to God’s call early in life, preaching Universalist doctrines from the steps of the Court House in Hamilton, Ohio, at age 17. This was about 1840. During the two decades that followed, he received a formal education as a theologian and ministered in several states, with the exception of a several year stint as a lawyer.

At the start of the Civil War he tended to the flock at the First Universalist Church in Boston, Mass. In the summer of 1861, he became chaplain of the 13th and was present for duty during the Battle of Antietam. He left the regiment six months later for Campbell Hospital, and served here through the war’s end.

Back in Boston, throat problems limited the eloquent Gaylord’s abilities as a pulpit orator. He entered politics as an elected representative to the state legislature, practiced law for a time, and clerked in the New York Custom House. At some point, he contracted consumption and succumbed to its effects in 1873 at age 50. His remains were brought home to Hamilton, Ohio, for interment.

Sickness and Its Lessons

On Dec. 13, 1863, Rev. Jacob Merrill Manning resumed his place in the pulpit of Boston’s Old South Meeting House. It marked the first appearance for the much-respected 39-year-old Congregationalist minister since October 1862, when he had left to preach in tents and the outdoors as chaplain of the 43rd Massachusetts Infantry. An ardent abolitionist, Manning had opened the Meeting House in mid-1862 as a recruitment station. According to church history, “over 1,000 men signed up under our steeple; they successfully convinced Manning to join them.”

Manning and his comrades spent the majority of their 9-month enlistment in North Carolina as part of Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside’s North Carolina Expedition. The Bay Staters acquitted themselves well during operations to secure the region for the Union.

Towards the end of his time in uniform, Chaplain Manning fell sick with malaria. The disease brought him to the brink of death. Arriving home in July 1863, more than five months passed before he felt able to return to his church duties. At moments, he doubted if he would ever regain strength enough to return to the pulpit.

His first sermon, “Sickness and Its Lessons,” went down in history as one of Manning’s most memorable. Though he did not directly mention the war or his role in it, Manning offered two observations that could only be made by a war veteran: “The beating of a child’s drum in the street is like the rapid firing of artillery” and “The invalid resembles soldiers just out of battle, sobered into speechlessness by the near vision of what they have passed through.”

Manning continued to preach despite health issues related to his wartime bout with malaria. He retired in March 1882, and died before end of the year. He was 58.

The Commission’s Man in Gettysburg

One of the most often photographed individuals following the Battle of Gettysburg might be the white-bearded man pictured here, Rev. Gordon Winslow, D.D., who served as the Sanitary Commission’s inspector for the Army of the Potomac. Winslow appears in numerous images of the Commission’s encampment.

A peacetime Episcopalian minister on Staten Island, N.Y., he started the war as chaplain of the 5th New York Infantry, popularly known as Duryée’s Zouaves. His profile in the regiment’s history reveals an indefatigable man: “He was a type of the old Revolutionary stock, possessing an iron constitution, capable of enduring any amount of hardship, with an active, untiring, energetic disposition. … “He was a man that knew no fear, and always was to be found on the advance line, sometimes even ahead of the skirmishers, and he never thought of danger or spared himself when he could be of any benefit to the wounded.” He could often be seen astride his favorite horse, Captive.

Zouave colonel and commander Gouverneur K. Warren, who later distinguished himself along the crest of Little Round Top at Gettysburg, confirmed Winslow’s worth when he wrote in early 1863 that the chaplain “has been constantly with me on the field, except when the claims of humanity and mercy called him to attend to the sufferings of his fallen comrades.”

In June 1864, less than a year after Chaplain Winslow completed his labors at Gettysburg, he traveled aboard the Commission transport Mary Rapley with his injured son, Col. Cleveland Winslow of the 5th. The young man had suffered a shoulder wound at Bethesda Church on June 2. As Chaplain Winslow attempted to draw a bucket of water from the Potomac River, he fell overboard and drowned. His body was never recovered. He was 60 years old. His son succumbed to the effects of his wound on July 7, 1864.

Witness to a Lieutenant’s Last Moments

During the 1862 Battle of Cedar Mountain, Chaplain Henry Rogers Pyne of the 1st New Jersey Cavalry responded to a severely wounded officer on a stretcher. Second Lt. Alanson Austin of Company M had just been carried from the field, one leg almost severed from his body at the thigh after being struck by enemy artillery. As he awaited the surgeon’s knife in a crude field hospital, Pyne recalled what happened next: “‘Oh, chaplain, if I could only pray!” he touchingly murmured, as his mind struggled against the dulling influence of the shock to his physical frame.”

Pyne, a peacetime Episcopal minister, uttered the soothing words of the order of the Visitation of the Sick by Austin’s side. “His lips moved in unison with the supplication; and the blessed associations of home worship, and love, and teaching, which cluster around the familiar words of the Lord’s Own Prayer, drew from him a sigh of softer utterance amid the low groans of his dying agony.”

Surgeons went to work to amputate the mangled leg as enemy artillery boomed. One shell struck a fence behind which the doctors worked and forced them to suspend the operation. Precious moments were lost. Yet, Pyne remained by Austin’s side. “As his life ebbed away his mind wandered under the influence of chloroform and in the delirium of exhaustion,” noted Pyne, adding, “He feebly waved his arm, and gave some orders as if still on the field. Then, with a half-articulate cry of ‘the Star Spangled Banner,’ his voice was hushed in death.”

During Pyne’s three years as chaplain, he tended to scores of wounded troopers at Brandy Station, Gettysburg and other engagements with the Army of the Potomac, as well as an uncounted number of sick men. He mustered out in late 1864. Seven years later his book, The History of the First New Jersey Cavalry, documented 2nd Lt. Austin’s tragic death and other events. Pyne died in Washington, D.C., in 1892. He was 57 years old. His remains rest in Washington’s Congressional Cemetery.

CASUALTIES

Wounded along the Bermuda Hundred Front

When the men of his regiment required assistance, Chaplain George Seymour Barnes acted without regard for his own safety. At one such perilous point during the Siege of Petersburg while assisting one of the men, a shell fragment hit him in the groin and landed him in the hospital for several weeks—a rare case of a chaplain who became a war casualty.

Those who knew Barnes would not be surprised to learn of his frontline efforts. A Vermonter named to lead the Episcopal Church in Littleton, N.H., in 1861, a town historian observed, “The new minister was an ardent patriot and divided his time fairly between the interests of the church and those of the nation.” The latter led him to become active as a recruiter of soldiers for the Union army and a chaplain in the 2nd and 17th New Hampshire infantries in 1862 and 1863.

In late 1864, he joined the 29th U.S. Colored Infantry as its chaplain. The regiment had been organized earlier in the year and fought hard at the Battle of the Crater and elsewhere along the Petersburg front. In late October 1864, the 29th moved to Bermuda Hundred. Chaplain Barnes joined the men in November. The regiment occupied this part of the line for about five months. At some point during this stay, Barnes suffered the shell wound.

Chaplain Barnes and his comrades departed Virginia for Texas after the fall of Richmond and surrender at Appomattox, and mustered out of the army in November 1865. Barnes “left the service with a high reputation for such soldierly and ministerial qualities as his position required,” noted Littleton’s historian.

In 1866, Barnes moved to Michigan and ministered in a number of churches during the next two decades. Following his retirement in the 1880s, he made his home in Petoskey, where he died in 1913 at age 83. Three daughters from his marriage to Sarah Lamb Barnes, who passed in 1880, and his second wife, Emma, survived him.

Captured After the Salem Raid

Brigadier Gen. William W. Averill’s raid to destroy the Tennessee and Virginia Rail Road in December 1863 began with the promise of success. The 2,500-man expedition included Chaplain Andrew W. Gregg of the 8th West Virginia Infantry, a Pennsylvania-born Methodist minister who originally commanded the regiment’s Company H. The 8th had been converted to a mounted regiment six months earlier.

On December 16, Gregg and the rest of Averill’s force hit the railroad at Salem, Va. They also encountered Confederates, who pursued them over icy roads and fast moving streams. About 120 Union soldiers fell into rebel hands, including Gregg.

The chaplain did not remain a captive for long. Gregg arrived in Richmond on Christmas Day and received a parole two days later. He returned to his regiment and mustered out in July 1865.

Gregg married Elizabeth Finley in Ohio after he left the army, and began a family that grew to include three children. They relocated to Indianapolis, Ind., where Gregg died in 1890 at about age 64. His grave in Crown Hill Cemetery is unmarked.

—Richard A. Wolfe

Close Encounter With Mosby’s Men

On June 11, 1863, Cpl. Henry S. Seage of the 4th Michigan Infantry cleaned a uniform coat caked in dried blood. The wearer of the coat was his father, regimental Chaplain John Seage.

Three days earlier, the Episcopal minister and English immigrant had set out on horseback from camp near Fredericksburg, Va., to Washington, D.C., carrying thousands of dollars, watches and letters to be sent home to soldier’s families in Michigan. About a dozen miles into his journey, according to an account in The 4th Michigan Infantry in the Civil War by Martin N. Bertera and Kim Crawford, a group of five mounted men armed with revolvers ordered him to halt and surrender. Chaplain Seage asked by whose authority, and the leader of the party told him—Mosby’s Cavalry.

Seage declined and took off on his mount. Three of Mosby’s men wheeled and let loose their revolvers. Four bullets struck Seage: one in the back through his left shoulder, another in the right wrist and two more in the ankle and thigh. Bleeding heavily, his hands practically useless, and barely conscious, Seage managed to stay in the saddle and outpace his pursuers.

About a mile further, Seage happened upon a detail of Union soldiers guarding a supply train—members of his own regiment. They recognized him immediately and got him and the valuables back to camp, where his son, Henry, and another one of his boys, 2nd Lt. Richard W. “Dick” Seage, attended to their badly wounded father.

Chaplain Seage went home to recuperate. Meanwhile, his sons and the rest of the 4th marched into the Gettysburg Campaign, where Dick suffered a wound during the fight on July 2. He left the army with a discharge before the end of the year. Henry survived the battle and continued on until the expiration of his enlistment in June 1864.

Chaplain Seage eventually rejoined his regiment and outlasted both of his sons in the service, mustering out in May 1866. He spent part of his time in Tennessee, where, according to Torn Families: Death and Kinship at Gettysburg by Michael A. Dreese, Seage received recognition as a humanitarian for exposing racial injustices.

Seage returned to the ministry after leaving the army and lived until age 73, dying in 1883.

At Fredericksburg, “I Must Do Something for My Country”

In a street on the edge of Fredericksburg, an unlikely drama played out during the mid-afternoon of Dec. 11, 1862. A Union captain in command of an advance detachment of 25 skirmishers had just entered the city when an older man in a staff officer’s uniform and musket in hand approached with a salute and a question. “Captain,” he said, “I must do something for my country. What shall I do?”

In this moment, the captain, Moncena Dunn of the 19th Massachusetts Infantry, took the measure of the man standing before him. “I thought he could render valuable aid, because he was perfectly cool and collected. Had he appeared at all excited, I should have rejected his services; for coolness is of the first importance with skirmishers, and one excited man has an unfavorable influence upon the others. I have seldom seen a person on the field so mild and calm in his demeanor, evidently not acting from impulse or martial rage.”

Capt. Dunn replied to the man “that there was never a better time than the present; and he could take his place on my left.”

The man took up a position in front of a grocery store as firing began to intensify. He squeezed off maybe two shots before rebel bullets struck him in the hip and arm, killing him. Dunn and his skirmishers were soon called back, leaving behind the man’s body.

The dead man was Chaplain Arthur Buckminster Fuller, Jr., of the 16th Massachusetts Infantry. A day earlier, he had received a disability discharge that left him technically out of the army. But he could not in good conscience leave his now former comrades on the eve of battle.

A native of Massachusetts and the son of a U.S. congressman, Fuller held a degree from Harvard, where he also studied in the Divinity School. As a Unitarian minister, his travels took him to Illinois, New Hampshire, and his home state, where he served two stints as chaplain of the Massachusetts legislature.

In the summer of 1861, he joined the 16th and distinguished himself in camp and on campaign. The active life took a toll on his health and prompted his resignation.

About an hour after his death, Capt. Dunn and his command returned to the scene with other forces. He recovered Fuller’s body, which had been robbed, and had it carried to Union lines. Word of his death quickly spread, and grief-stricken soldiers came to pay respects to Fuller’s remains, which lay covered with a white cloth on a crude wood board.

The remains were transported to Washington, D.C., embalmed, and sent to Boston for a large public funeral on Christmas Eve. The plate on his casket was engraved with the words, “I must do something for my country.” He was 40 years old.

After Gettysburg, “It Was Hard to Say ‘I Surrender’”

The service of Louis Napoléon Boudrye as chaplain of the 5th New York Cavalry put him in a position to minister young soldiers facing life and death—and to fall into enemy hands two days after the Battle of Gettysburg. In a letter written soon after the event, he explained how enemy cavalry belonging to Brig. Gen. Albert G. Jenkins’ brigade surrounded and captured him and others. “It was hard to say ‘I surrender,’” Boudrye admitted.

His captors told him that he would be released and allowed to take his horse with him once they arrived at the headquarters of Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart. “True as the chivalry are able to be to their promises, on reaching the general, I was immediately released—of my horse and of all hopes of liberty,” quipped Boudrye.

Not all the rebels were bad, he noted. The day after his capture, after an exhausting march with little food, the column of prisoners was halted. Boudrye and his comrades made their way to soft grass to sleep. “I had just fallen into a doze, when I was roused up by a strange voice, calling ‘Chaplain Fifth New York Cavalry.’ Looking up, I beheld a Rebel lieutenant, with whom I had conversed a little during the day, who stepped up toward me with a cup of smoking hot coffee and a fine piece of warm bread. ‘There, chaplain, I thought you might be hungry, and brought you this for your supper.’ I was quite overcome with gratitude at an act so unexpected and so rare, and my heart leapt up for joy, as at the sight of the first flower of spring. That, I think, was a noble man, though he was a Rebel, and I have not found another among them like him.”

Boudrye and the others continued into Virginia and on to Richmond’s Libby Prison. He put his college education from New York’s Troy University to work as a teacher to keep his fellow inmates’ spirits up and also edited a handwritten weekly prison journal, The Libby Chronicle.

Boudrye spent about three-and-a-half months in Libby before he received a parole. He returned to the regiment after his exchange and remained in uniform until July 1865 when the 5th mustered out of service. He returned to his life as a Methodist clergyman in New York, New England and in Canada. In 1891, his work brought him to Chicago, where he died of pneumonia a year later at age 58. He outlived his first wife, Celeste, who died before the war. His second wife, Pearlie, and seven of their children survived him. Boudrye also left behind the Historic Records of the Fifth New York Cavalry, The Libby Chronicle and other writings.

“The Famous ‘Fighting Chaplain’”

The loss by the Union Army of the James at the Battle of Drewry’s Bluff, Va., on May 15, 1864, effectively ended its advance on Richmond. Days later, the rebels struck again at Ware Bottom Church, inflicting heavy losses on the boys in blue. The casualty list included Maj. Nathan Gibbs Axtell of the 142nd New York Infantry, who suffered bullet wounds in the neck and thigh. According to one source, Axtell remained on the field despite his injuries and held five companies on the right of the regiment’s line against superior enemy forces.

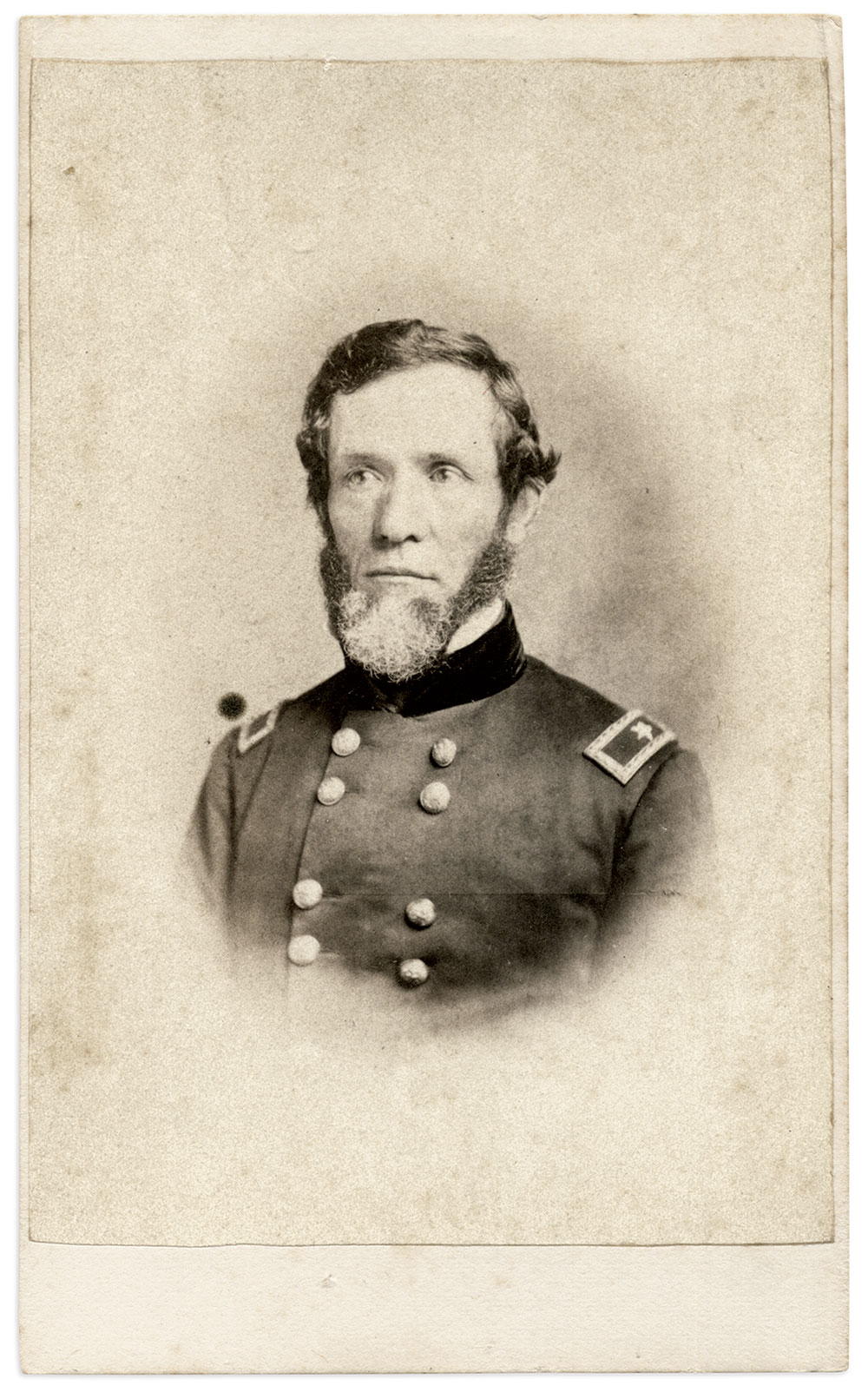

The Confederates who shot Axtell could not have known that he was a Methodist minister. A 33-year-old preacher in Vermont when war broke out, he returned to his home state of New York and joined the 30th Infantry as chaplain. He’s pictured here wearing the uniform of his rank.