By Ron Field

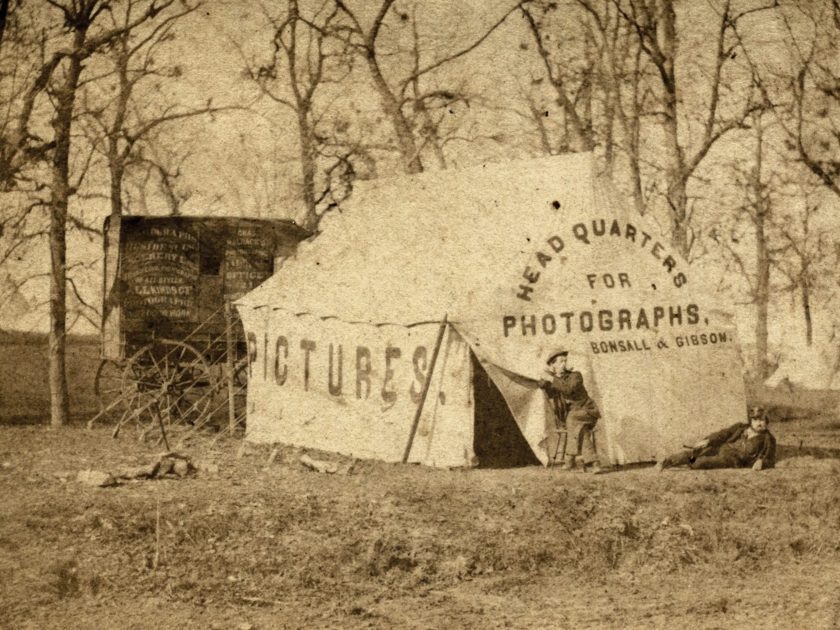

Virtually every military encampment had a traveling photographer nearby or within its limits during the Civil War. This was particularly true in the North, where photographic chemicals and supplies were readily available throughout the conflict.

Newspaper correspondents occasionally commented on the presence of these enterprising individuals. With the Union Army of Virginia’s Ninth Corps, near Fredericksburg, Va., a correspondent for the New York Tribune declared on Aug. 20, 1862, “Decidedly one of the ‘institutions’ of our army is the traveling portrait gallery. A camp is hardly pitched before one of the omnipresent artists in collodion and amber-bead varnish drives up his two-horse wagon, pitches his canvas-gallery, and unpacks his chemicals. Our army here is now so large that quite a company of these gentlemen have gathered about us. The amount of business they find is remarkable. Their tents are thronged from morning to night, and ‘while the day lasteth’ their golden harvest runs in.”

With the Army of the Cumberland in Tennessee and Georgia in March 1864, a reporter for the Boston Traveler wrote likewise, “It is remarkable with what persistence the army photographer follows up his profession. I saw the tent of one of them the other day with our advance at Morristown, and another with the forward brigade at Ringgold. They do a good business, for if the soldier has one great weakness it is to have his likeness taken. A good portion of his pay goes in this way, and the mails are loaded with the shadowy momentoes [sic] he sends to those at home.”

As the war progressed the traveling “artist” could not simply arrive at a military encampment and start plying his trade. Federal measures to pay for the Civil War introduced by the second Revenue Act of July 1, 1862, and implemented during the following October, required photographers in the North to apply for a license to work in Union Army encampments. They also had to register with the camp provost marshal, or military police chief, before setting up a campsite gallery and were assigned to specific brigades within divisions and army corps, or requested permission to be attached to the same.

Based on two listings of approved “photographists” which survive in the National Archives, one of which was compiled during the winter and spring of 1862-63, and the other either in 1864 or 1865, at least 56 photographers supported by 99 assistants or clerks were licensed to operate within the Army of the Potomac. Documentation on the number of army photographers following the Union armies in other theaters of the war has not survived.

Red tape and other bureaucratic details

Little specific information survives regarding these licensed photographers and their assistants. On Dec. 22, 1863, E.W. Blake, of Philadelphia, wrote to Brigadier General J.H. Hobart Ward asking if he could “act as Photographer and Ambrotypist” for the 2nd Brigade, 1st Division, Third Corps, of the Army of the Potomac.

On Nov. 5, 1864, Gideon Smith was authorized by Brig. Gen. Robert Potter to set up “a Photograph and Ambrotype Gallery” for six months within the 2nd Division of the Ninth Corps, by Brigadier General Robert Potter. Joining that division outside Petersburg, Va., he was granted permission to employ “two assistants … and take with him subsistence … and all the necessary appliances for his party.”

Thomas P. Adams, a photographer with roots in the daguerreian era before the war, had an extensive campsite operation by January 1864 involving a partner and four different establishments. On the 15th of that month, Provost Marshal Brig. Gen. Marsena R. Patrick ordered Adams to provide further details about his business as “photographer in the Army of the Potomac” as not all of his operatives had been registered. He explained that his partner was the already well-established photographer Stewart Bergstresser, with whom he divided all profits, while others in his employ were paid a salary “per day.” Adams catered to the 2nd Division of the Second Corps with two assistants.

Photographers were issued passes by the Provost Marshall General’s Office, which permitted them to “move within the lines,” and sometimes faced the consequences of failing to acquire such permission. Attached to the Engineer Corps in Virginia, photographer J.H. Nolan was arrested in January 1864 for attempting leave Rappahannock Station on a train without a pass.

Photographers also needed to declare the materials and equipment they carried with them into military encampments. On March 27, 1865, James Coleman wrote to Lt. Col. F.L. Manning, the Provost Marshal General of the Army of the James, asking if he could ship the following from Washington, D.C., to Bermuda Hundred, “Nine Boxes Plates, Three & Half Gross Matts, Four Dozen Union Cases, Two Negative Boxes … One Thousand Envelopes, One Thousand Cards … Fifty Sheets Albumen Paper … [&] One Scenic Background.” The inclusion of plates, Union cases, and card indicates that Coleman was producing cased ambrotypes or tintypes and cartes de visite in front of a painted backdrop.

Primitive studios packed with soldiers

The photographic studios established under canvas were quite primitive compared to the galleries found in cities and townships. In order to permit sufficient sunlight for the camera lens and plate, panels cut in sloping tent roofs were rolled back. Lacking the space for much in the way of furnishings and trappings, the photographer usually attempted to create a parlor-like setting in his studio area by using simple props such as a chair and table covered with cloth. Like James Coleman, many campsite artists managed to incorporate painted screens as backdrops showing military settings or Greek classical revival-type scenery. Others simply used a plain white screen in front of which their eager customers either stood or sat to have their likeness taken.

Both photographic and written evidence indicate that campsite galleries were often crowded with soldiers anxious to have their image made to send to the folks at home, especially when regiments of new volunteers arrived. En route for Lookout Valley, Tenn., on Oct. 4, 1863, 2nd Lt. Peter C. Sears of the 33rd Massachusetts Infantry wrote to his sister Amelia from Bridgeport, Ala., “There is an ambrotypist near hear [sic] and I intend to have a picture taken as soon as possible. You must not expect a very nice one. They only cost one or two dollars.” As Sears was a teacher at the State Normal School in Bridgewater, Mass., before the war, he was probably wealthy enough to have afforded a more expensive image than that expected from the Bridgeport photographer.

In a letter to his sister from Fortress Monroe, Va., on April 27, 1864, Pvt. Levi McLaughlin of the 3rd Pennsylvania Heavy Artillery explained, “I just come from Camp Hamilton. I was there to get my likeness taken on purpose to send to you … but I never got it taken … But I will … when I get my dress hat if I am here yet.”

The need to be photographed in uniform before the end of the war is apparent in a March 4, 1865, letter written by Pvt. Charles Parker of the 31st Maine Infantry to his sweetheart Clara Dyer. Encamped near Parker Station, Va., he wrote, “Our regiment was paid last Wednesday and the [photographer’s] saloon is so full that I could not get near it or I would have had an ambrotype taken to send you.”

Prop weapons, coached poses and informal scenes

Providing an example of how weapons were supplied as props by some camp photographers, Vincent Anderson, who served as a private in the 21st Indiana Infantry (later 1st Heavy Artillery), recalled, “As soon as I donned my soldier suit I made, like the rest, for the artist [who] was alive to his business, and who kept some guns and swords to place in the hands of the soldiers who wished to get their pictures. He was also an expert in showing us how to take the position of a soldier. When I went to get my picture taken and he saw I was a private he took a musket with the bayonet fixed and knelt down and showed me how to form a hollow square out of myself and resist a cavalry charge. I at once took to his idea and down on one knee I went, and with the gun and bayonet, as directed, my picture was taken. I got a dozen of them as soon as I could and took them down to camp, and about the first one I showed them to was Will Westfall, our closest neighbor boy and my mess mate all the time I was in the service. When he got hold of one of them he hollowed out to the boys to ‘all come here,’ and when a crowd had gathered around he showed them that picture of mine and said: ‘Oh! hell boys, let us all go home; it is not a bit worth while for any of the rest of us to go!’… It makes a creepy feeling run up and down my back even now to write about the pictures that I destroyed and got others less fierce to pass around.”

An example of how certain less formal campsite poses came to be produced in some images is revealed in a letter written from New Berne, N.C., by Pvt. Alfred Holcombe of the 27th Massachusetts Infantry, on Aug. 22, 1862, “I had my picture taken yesterday. I will send it to you. it is not a very good one. It was late in the day. I am goin to have another taken in a few days. Chauncey [Holcombe] and I am goin to have one taken together. I thot that I wo[u]ld let you see in this one how we eat our grub siting on the ground with our knapsacks for a table with a piece of canvas for a covering only.”

Confederate camp photographers

Although traveling photographers operated in and around Confederate encampments at the start of the war, they became far less prevalent as the Union naval blockade increased in efficiency and prevented essential chemicals, paper and other supplies from reaching their destination. With an “ambrotype saloon” at 173 Rampart Street, Elizabeth Beachabard was a rare example of female gallery proprietor advertising in New Orleans in 1861. During May of that year, the Daily Picayune suggested that a photographer was needed at Camp Moore, the rendezvous and training ground for Louisiana volunteers situated north of Lake Pontchartrain in Tangipahoa Parish: “Posterity will have a fine chance of being delighted. Their pictures may be taken by the thousand.” Beachabard appears to have responded to this advice. On May 21, 1861, a report in the New Orleans Bee described the layout of Camp Moore and referred to what may have been her studio as “the shanty of an enterprising ambrotype artist, who furnishes handsome warriors with their ‘counterfeit presentments.’” Beachabard died and was buried at Camp Moore of unknown causes on Nov. 22, 1861.

Writing from Camp Mangum, near Raleigh, N.C., in May 1862, Pvt. James K. Wilkerson of the 55th North Carolina Infantry advised his parents on June 13, 1862, that he wanted to have his “pikter taken,” adding “I dont know as you all will ever have the opportunity of See[ing] me any more or not.” Wilkerson survived the war and was among the sick paroled at General Hospital No. 12 in Greensboro, N.C., on April 28, 1865.

“Mother I got mi amber tipe taken when I was at Richmond and I went up to the baggage car and giv it to brother Joseph to doo up and put in the [mail] office as I left camp that morning”

Prior to departure from his encampment near Richmond, Va., on May 1, 1862, Pvt. Jefferson Quattlebaum of the 13th South Carolina Infantry had his photograph taken and asked his older brother Joseph, who served in the same regiment, to send it home for him. Dutifully mailing off a package containing the image, Joseph explained to his mother in an accompanying letter, “Jefferson had his [ambro] tipe [sic] taken today and as he did not haf time to write … and send his tipe to you … I will do with pleasure.” At a later date Jefferson wrote home explaining, “Mother I got mi amber tipe taken when I was at Richmond and I went up to the baggage car and giv it to brother Joseph to doo up and put in the [mail] office as I left camp that morning … If you get the picture rite to me and let me no if it looks like me … Mother, the picture did not cost me but $3 be Side the postage on it…”

A French-born photographer at Henderson, Texas, before the war, David Le Rosen operated a gallery at Shreveport, La., as late as May 1863. After visiting Le Rosen on May 20, 1863, Asst. Surg. Junius N. Bragg of Crawford’s Battalion of Arkansas Infantry wrote a letter to his wife. In it, he described the conditions of the studio and revealed that clothing and weapons were used as props by some photographers. According to Bragg, “The Gallery was a little den of a place with its sides covered with old faded blue cambric, and two little rickety screens. The floor was of pine slabs, as well as I could judge through the stratum of dirt and wash, which had been apparently accumulating for the past half dozen years. There were fifteen soldiers ahead of us, who were going to have their ‘picture took.’ As each one brought from one to four friends with him, to see the operation, they made quite a sizable crowd, in the ‘Gallery,’ which was not sixteen feet square. All these men had their Ambrotypes taken in the same jacket – a black one, with blue collar. Eleven of the number, had a large old rusty ‘Navy six shooter’ in their hands, which made the warriors look very sanguinary. No doubt their friends will think they are all well uniformed and all armed with pistols. They all wet their long ambrosial locks and slicked them down, so as to look ‘gay and festive’ … [Mine] is not a good picture, and as I never did get a good one, I do not think I am one of those who take well.”

Reflecting the high price of photographic supplies caused the Union naval blockade and the inflated Confederate dollar, Bragg concluded, “I only paid forty dollars for it.”

References: Peter E. Palmquist & Thomas R. Kailbourn, Pioneer Photographer from the Mississippi to the Continental Divide: A Biographical Dictionary, 1839-1865; Nashville Daily Union, Nov. 26, 1862; NARA M345. Union Citizen’s File; “Various Listings of Official Army Photographers during the Civil War,” courtesy of Bob Zeller; Spared & Shared website 9 & 10; Vint Anderson, “As a Private Saw It, Not as History Records It,” Indianapolis American Tribune, date unknown [1898–1900], in “Experience of a Private of Company B, 21st. Ind. Vol. Inf. and 1st. Ind. H. A.,” scrapbook. Owen County Public Library; Henry C. Lind (ed.), The Long Road for Home: The Civil War Experiences of Four Farmboy Soldiers; Daily Picuyune, May 24, 1861; New Orleans Bee, May 21, 1861; Margaret Denton Smith & Mary Louise Tucker, Photography in New Orleans: The Early Years, 1840-1865; NARA M270 Compiled Service Records – North Carolina; Quattlebaum letters courtesy of Terry Burnett – see also “Joe Quattlebaum’s War,” Military Images (Spring 2017); T. J. Gaughan, Letters of a Confederate Surgeon, 1861-1865.

Ron Field is a retired history teacher who has researched and written Civil War history for nearly 40 years. He was associate editor of the Confederate Historical Society of Great Britain from 1983 to 1992, and elected a Fellow of the Company of Military Historians in 2005. He received the Emerson Writing Award in 2012 following the publication of his article “The New Hampshire Volunteers of 1861” in Military Collector & Historian. He became a senior editor of MI in 2014, and has contributed images and articles to the magazine since 1998.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.