By Jack Hurov

On a warm and windy morning in April 1862, an international incident occurred at the mouth of the Rio Grande River. A group of American citizens, ranging from 50 to 100 in number, disembarked from the Mexican steamer Matamoras, and waded through the shoals to sage and acacia-covered sandbars. There, they awaited surfboats dispatched from the U.S. gunboat Montgomery. Anxious sailors aboard the Union vessel watched the crossing with concern as southeasterly winds whipped the waters.

How these Americans came to be on the Mexican steamer represents a tale of four countries. After recent French incursions into Mexico resulted in destruction of the American consulate in Matamoros, Texas rebels crossed over from the Lone Star State. Aided by Mexican police, the Texans arrested and jailed the Americans.

This act placed Mexico in a precarious position. The event could potentially raise suspicion in the U.S. government about its neighbor to the south, and judge it in league with the Confederacy. Negotiations ended with what might be considered a prisoner exchange at the Rio Grande on April 26. The wet and bedraggled Americans who clambered into the cutters bound for the Montgomery that morning included William Tyler Cross.

The international entanglement became part of a wartime experience that led Cross to a unique navy assignment.

Cross, a 26-year-old, 6-footer with a dark complexion, was born in the vicinity of another important water feature—New York’s Finger Lakes region. Little is known of his early life other than serving a one-year stint as a sailor aboard a New Bedford whaler. By January 1861, he had journeyed to the rolling hills of central Texas, where he worked as a teamster, or wagon-master, hauling supplies west from San Antonio to Fort Lancaster.

Years later, he told a tall tale about this period of his life. He claimed service in the Quartermaster Department of the Confederate army, attached to Capt. William T. Mechling’s Texas Battery, and moreover claimed he had escaped, fleeing to Brownsville and thence to Matamoros. He may have created this fabrication to explain his capture in Mexico and subsequent exchange to Union authorities.

Making the Navy home

Sheltered aboard the Montgomery, Cross and the other refugees received food and clothing. All were bound for New Orleans, which fell to Union Flag Officer David Farragut and his fleet on April 28, only two days after the exchange.

After landing in the Crescent City on June 5, 1862, Cross enlisted for a 3-month term in the Navy as a landsman aboard the Richmond. A 3-mast, steam-powered, propeller-driven sloop, the gunboat mounted 16-22 guns, including Dahlgrens and a Parrott rifle, and carried a crew of about 220 officers and men. Cross’ enlistment coincides with the Richmond’s critical role in initial operations against Vicksburg between May-July 1862. The gunboat also provided armed escort for supply steamers.

Cross received a discharge at New Orleans in November. He re-enlisted two weeks later, and rejoined the Richmond as a Surgeon’s Steward with the rank of petty officer. Little evidence exists that he had any land or sea-based training to fulfill this important, yet little recognized position in the navy.

The duties of a surgeon’s steward resembled those of its Army counterpart, a hospital steward. A term first appearing on Navy pay charts in 1841, the primary responsibility of the surgeon’s steward was to assist the shipboard surgeon and assistant surgeon, to maintain the ship’s medical department and drugstores, and to supervise nurses.

A host of secondary duties included stocking the dispensary with drugs, chemicals and instruments, preparing and administering medicines as ordered by the attending surgeon, and preparing reports. The surgeon’s steward also attended patient rounds, performed triage for treatment and hospital admissions, and, in the absence of the surgeon, made diagnoses and provided treatment in the form of dressing wounds and conducting minor surgeries. Dental care and preparation of deceased personnel for burial at sea also fell under his authority.

Cross likely had similar duties shipboard. Considering the 220-man crew of the Richmond, he was probably one of the busiest men aboard the vessel.

Tested at Port Hudson

As Cross adjusted to his official duties, naval operations along the Mississippi River remained fluid. Farragut’s victory at New Orleans led to the fall of the Louisiana capital, Baton Rouge, and secured the lower Mississippi for the Union. Further north, the mighty river and its tributaries—the Red, Atchafalaya, and Black Rivers—remained in Confederate hands. As long as these critical lifelines remained open, they provided the means for transporting men and materiel to the Southern strongholds of Vicksburg and Port Hudson.

In mid-February 1863, Union efforts to shut down these lifelines began along the Black, when a fleet of rams commanded by Charles R. Ellet engaged Confederate naval forces and shore batteries at Gordon’s Landing, La. The fight ended with loss of two of Ellet’s ships, the Queen of the West and DeSoto. Confederates took out another vessel, the Indianola, along the Big Black River before the end of the month.

“Considering the 220-man crew of the Richmond, Cross was probably one of the busiest men aboard the vessel.”

Farragut responded with a bold attack against Port Hudson. During the night of March 14, he ran a flotilla of seven vessels past the heavily fortified slopes and armed summit of Port Hudson. Four warships and three gunboats composed a single attack column; each of the smaller and more vulnerable gunboats was lashed to a larger and more powerful warship.

Second in line was Cross and his crewmates aboard the Richmond, lashed to the gunboat Genesee.

During the two-hour battle, the flotilla was pounded by Port Hudson’s formidable defenses. All hell broke loose aboard the Richmond when cannon shot caused extensive damage to the power plant. The crew worked frantically to restore damaged steam lines without success. The smaller Genesee came to the rescue, towing the helpless Richmond to safety.

Cross and other medical personnel tended to casualties—three killed and a dozen wounded. He also aided the crew from a sister warship, the Mississippi, after it caught fire and eventually exploded. The men abandoned ship and became stranded on a levee. Cross recalled, “A great many of her crew got ashore on the Louisiana side and walked down the levee opposite our vessel and were taken on board. All these men had to be cared for in addition to our own sick and wounded.”

Only two ships in the flotilla successfully navigated the batteries of Port Hudson. Though Farragut suffered the loss of the Mississippi and more than 200 casualties, his sortie re-established control of the Mississippi above Port Hudson.

Following protracted and unsuccessful land-based assaults that May, the Port Hudson campaign evolved into siege operations. The Richmond’s crew played its part, lobbing 70-pound projectiles from its quartet of smoothbore Dahlgrens at enemy positions.

On July 9, 1863, the garrison of Port Hudson capitulated after the surrender of Vicksburg five days earlier had made its position untenable.

With the Mississippi now in Union control, the battered and bruised Richmond made its way to the New York Navy Yard in Brooklyn for maintenance and repairs.

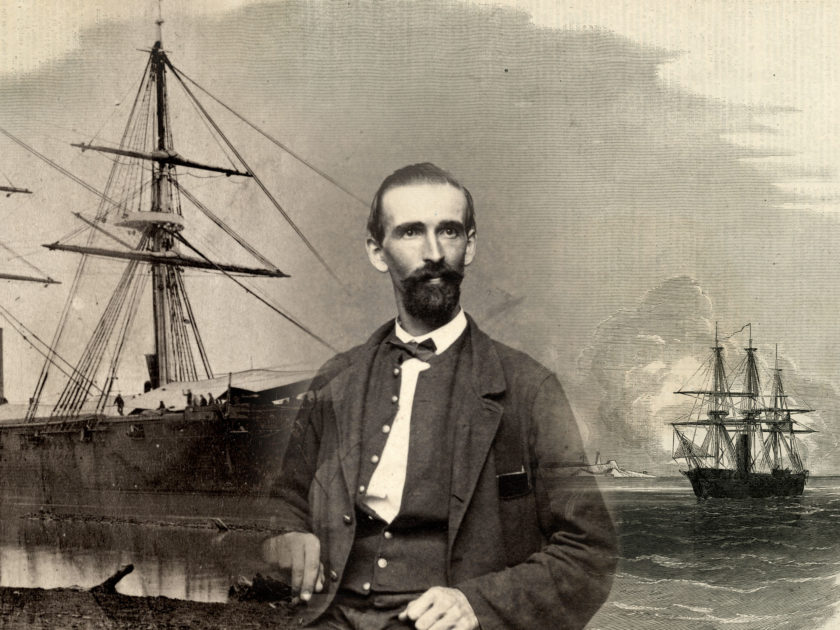

On August 13, Cross’ second tour of duty on the warship ended with an honorable discharge. One week later in Manhattan, he stepped into the Broadway gallery of photographer George W. Barnett and sat for this portrait. His uniform, a plain, single-breasted coat lacking insignia, is consistent with a surgeon’s steward. Beside him sits what appears to be a summer pattern sennit hat.

Epilogue

Cross returned to his family in the Finger Lakes community of Conesus. About a year later, he relocated to Peoria, Ill., where, on July 4, 1864, he married Melissa Anna Peet. How they met is unknown. Considering Peoria’s proximity to the Mississippi River, it is plausible that they met during the war. They began a family that grew to include a girl and a boy. Cross supported his family as a stone mason, specializing in marble monument sculptures. He became a member of Peoria’s local Grand Army of the Republic post.

During his post-war years, Cross suffered with catarrh, or inflammation of the nasal and oral mucous membranes and airways. His condition may have resulted from a wartime bout with malaria, which he claimed when he applied for a pension, or might have been job-related. Whatever the cause, it seems he struggled with chronic upper respiratory tract infections.

Cross died in 1901 at age 65 from complications due to glandular tuberculosis, a condition affecting his lymph nodes and lungs. He is buried in Springdale Cemetery and Mausoleum in Peoria.

His wife, Melissa, died in 1920—the same year the Richmond was burned for scrap.

Special thanks: The author is indebted to Ron Field for his generous assistance during the research phase of preparing this article. Ron, an MI Senior Editor, provided access to valuable resources and unhesitatingly answered numerous questions. He reviewed an earlier draft of this article, prompting significant improvements in its quality.

References: Official Records, Union & Confederate Navies; Findagrave.com; National Archives, Civil War Navy Widows’ Certificates; Moneyhon and Roberts, Portraits of Conflict-A Photographic History of Louisiana in the Civil War; National Archives Records Bureau, Naval Personnel 1798-2007; Canney, Lincoln’s Navy Ships-Men & Organization, 1861-5; Dougherty, Ships of the Civil War 1861-65: Illustrated Guide to the Fighting Vessels of the Union & Confederacy; Todd, American Military Equipage, 1851-72; Boston Daily Advertiser, Feb. 10, 1862; History of the Hospital Corps, United States Navy; Earp, ed., Yellow Flag: Civil War Journal of Surgeon’s Steward C. Marion Dodson; Moore, editor, The Rebellion Record: A Diary of American Events; American Annual Cyclopedia & Register of Important Events of the Year:1863; Roster of the Dept IL, GAR, 1896; Palm Beach Post, June 14, 1920.

Jack Hurov is a retired physical therapist. He took his first step down the rabbit hole of Civil War collectibles in the early 1990s, where he has been happily lost, ever since. Jack still owns the first several Civil War images he purchased. Beginning with the Winter 2014 issue, he has served as Copy Editor of Military Images. This represents his first article in the magazine, though photographs from his collection have appeared in previous issues.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.