By Elizabeth Topping

Immense throngs of New Englanders packed the halls of the weeklong Boston Sanitary Fair in December 1863. Generous crowds filled fundraising coffers with an impressive amount of money to benefit Union soldiers. The fair ended in success a few days before Christmas, and organizers tallied receipts—$146,000, or $3 million in today’s dollars.

The individual who led the fair’s organizational effort, Ellen Cheney Johnson, belonged to the New England Women’s Auxiliary Association. She personally visited every town and city in Massachusetts to solicit money, goods and supplies for the event.

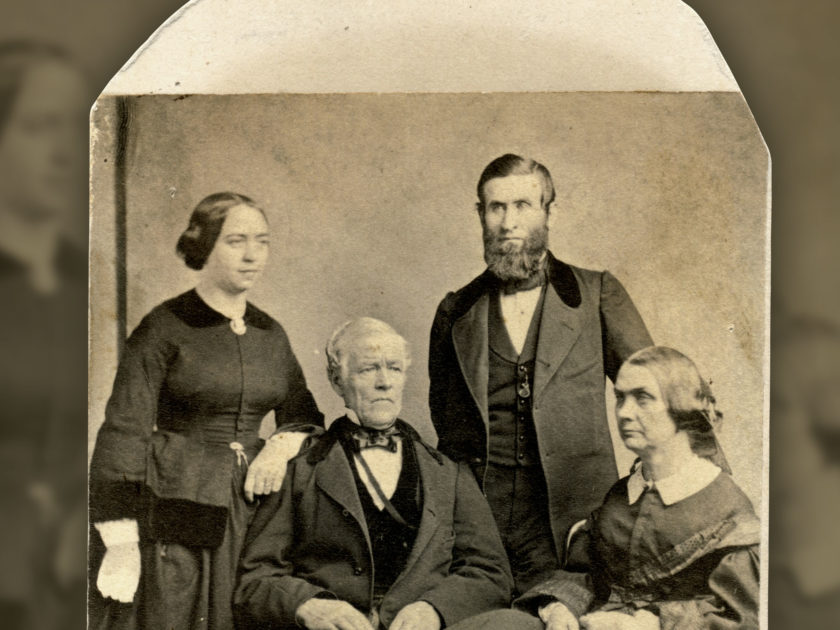

Kind and tenderhearted, Cheney Johnson had a long and active interest in social reform. In 1837, at age 18, she joined the Temperance Guild and made it a mission. She did so with the encouragement of her parents, Nathan and Rhoda Cheney. Her father, a cotton mill agent who traveled throughout the country, often took her, his only child, with him. Along the way, he taught her life lessons usually reserved for boys, including confidence building, leadership skills and business acumen. According to one biographical sketch, he “taught her to fish, swim and ride on horseback, as well as to attend to the lighter duties of the farm, especially the care of the young animals and of the plants and flowers.” She also gained an education at private schools in New Hampshire. Cheney married a wealthy Boston merchant, Jesse Crane Johnson, in 1838.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Cheney Johnson rallied ‘round the boys in blue and devoted herself to the soldiers’ welfare and care. She was a major influence in the creation of The New England Women’s Auxiliary Association, founded in Boston in December 1861 as a branch of the United States Sanitary Commission. She served on the Auxiliary’s finance and executive committees.

To better appreciate Cheney Johnson’s role, one needs to understand that the Auxiliary was a vast regional network organized something like an army. A total of 750 societies funneled their contributions through the Auxiliary, which, in turn, forwarded them to the Sanitary Commission for distribution. One member of each society was assigned as a correspondent to the Auxiliary, through which information was exchanged so that “every sewing-circle may know at once what is most needed; so that not one unneeded stitch may be set.” The Auxiliary sorted and tagged every article so its soldier recipient would know from whom it came. A person was appointed to occupy the committee’s rooms to answer inquiries, furnish patterns, and supply information, as desired. Contributors were encouraged to visit the rooms to see the volunteers in action.

The results of the organization spoke for itself. The Auxiliary sent massive amounts of clothing, food, medicine, reading and writing materials, games and other sundries to hospitals and camps as supplements to provisions provided by the federal government.

Cheney Johnson raised $40,000 for the Auxiliary, traveling all over New England for the cause. She paid her own travel expenses, with the exception of train fare, when on business for the Sanitary Commission.

No article entrusted to us shall be diverted from its purpose, and not one cent wastefully or unnecessarily spent.

Cheney Johnson was mindful of waste. In a circular entitled “To the Women of New England,” she stated that individuals who donated to the Auxiliary were promised, “no article entrusted to us shall be diverted from its purpose, and not one cent wastefully or unnecessarily spent.” Such articles, including purchased or donated fabric, landed in the hands of poor women to cut and sew into garments for the soldiers. Wealthy benefactors paid them for their work, thus serving to aid both the soldiers and the impoverished. No money was ever taken from the general fund to pay the seamstresses.

During the first half of the war, Cheney Johnson listed her name in annual Auxiliary reports as E.C. Johnson, the initials effectively hiding her gender. For the remainder of the war, she identified herself as Mrs. J.C. Johnson, embracing the recognition this naming convention would bring. The transformation is significant when one considers that she left the comfort of a woman’s sphere—the domestic domain—to enter the world of business, which was dominated by men. Cheney Johnson may have felt uncomfortable listing her proper (married) name, perhaps believing that she would have not been taken seriously in the role, or mocked by both the men and ladies in her social circle. It took time for her to build enough confidence to put her full proper name on the books. Cheney Johnson had matured into a woman sure of herself, comfortable assuming a stronger role in social concerns heretofore reserved for men.

Cheney Johnson’s charitable work on behalf of Union soldiers led to her involvement in the war against poverty. She and a friend, Hannah Chickering, were assigned to look after the destitute soldiers’ families in the poorest section of town. Many soldiers’ dependents and survivors struggled to make ends meet in the north end of Boston, and found themselves inmates of jails or workhouses. Women were often sent to Deer Island’s House of Industry, an almshouse created to accommodate the poor. In prison, female inmates and their children were housed in the same facilities as the men. They suffered mental and physical abuse from the male prisoners, as well as from the male guards and superintendents.

On April 30, 1864, in Dedham, Mass., Cheney Johnson and Chickering established the Dedham Temporary Asylum for Discharged Female Prisoners. The facility provided “shelter, instruction, and employment for such women as have been discharged from the Correction Institutes of the State, and who, with a desire to reform, have no home but the abode of vice and misery… Instruction was given at the Asylum in all branches of domestic service and needlework and in the basic elements of a common school education, and arrangements were made to find employment for the inmates after leaving the asylum.”

Meanwhile, the Auxiliary continued to provide aid to soldiers. When the organization disbanded on July 12, 1865, its leadership resolved to use the remaining $6,462.14 in funds to support disabled soldiers, war widows and orphans.

Cheney Johnson’s executive ability and increased influence enabled her to continue her good work after the war ended. She served on the Board of Prison Commissioners in 1879. She accepted the role of Superintendent of the Reformatory Prison for Women at Sherborn, Mass., in 1884, and worked diligently for the rest of her days.

In June 1899, Cheney Johnson traveled to London to address the conference of the International Council of Women, a world organization founded for the advancement of women. On June 27, press reports stated that she “described the success of women’s reformatories in that state, advocating a system of trades whereby women might regain their self-respect.”

The next day, she unexpectedly died. Her obituary in the Boston Evening Transcript noted, “It is believed she expired from heart disease, resulting from excitement in reading her paper yesterday.” She was 79.

Cheney Johnson was cremated, and shipped to Cambridge, Massachusetts, for burial alongside her husband, who had passed in 1880. She lies beside him in lot 3708 in Mount Auburn Cemetery, in the family plot with her parents.

References: Branch of the Sanitary Commission, Annual Report of the New-England Women’s Auxiliary Association. No. 22; Brockett and Vaughan, Woman’s Work in the Civil War; Harvard University Library, Arthur and Elizabeth Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America; Dedham Temporary Home for Women and Children, Records, 1864-1986; Radcliffe College, (April 1990); Mount Auburn Cemetery; Boston Evening Transcript, June 28, 1899; Ware, To the Women of New England; Biographies of Notable Americans; Boston Globe, June 28, 1899.

Elizabeth Topping has been a reenactor and living historian for more than 25 years. Her collection and research focuses on the social and material history of the Civil War years. Her initial study centered on the subject of prostitution, which ultimately led to research on abortion, birth control and childbirth, female job opportunities and working conditions, medical treatment for poor and insane women, class and sex restrictions imposed on 19th-century females, the roles actresses played in society, and the parts women played in aiding the war efforts. Elizabeth enjoys sharing her expertise and artifacts for use in television programs, museums, magazines, conferences and roundtables.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.